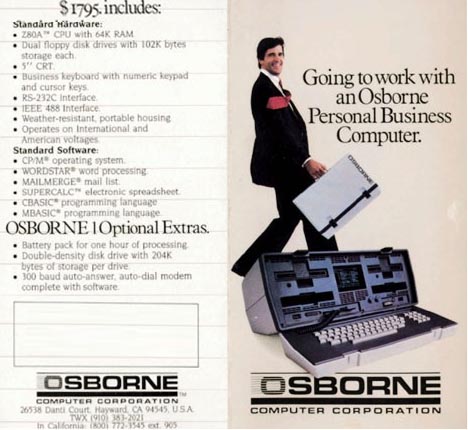

Just a few decades back, the painter Erik Sandberg-Diment was worried about providing for his family so he became a journalist to make money. In 2015, that sentence is enough to make you laugh and cry.

He ended up focusing on computers, tested out so-so cooking software, reviewed the Macintosh with less-than-full appreciation and famously whiffed on the future of laptops. Right or wrong, he was always an entertaining curmudgeon throughout the early PC period, with all its pre-Web frustrations.

Here’s what he said in the NYT in 1985 about computer banking and email:

Central to the new videotex is the concept of home banking. For the vast majority of people and businesses, however, banking-by-computer is about as convenient as fishing pickles out of the barrel with a toothpick. Home banking programs, even the heavily promoted Pronto sponsored by Chemical Bank, have grown far slower than predicted. V IDEOTEX services claim they will eventually include such features as stock brokerage, travel services, catalogue shopping and even housing exchanges. I doubt, however, that many people will give up shopping in person for the chance to buy a new refrigerator or washing machine by pressing a few keys on a personal computer.

This is a nation of tire kickers, after all. I can’t help but shake my head at the millions of dollars being spent on the development of videotex applications by companies that simply do not seem to grasp the fundamental tenets of personal computing. Personal computing is timesaving, money saving and fun. Videotex is none of the above. ”There have been a lot of very high expectations for information services that have not been met by either teletext or videotex,” says Michelle Preston, the technology industry analyst at the investment firm of L. F. Rothschild, Unterberg, Towbin. ”They simply do not offer enough value to really take off.”

Then there is electronic mail, that thoroughly modern offspring of a calcified postal service and a splintered Ma Bell. Currently, the companies promoting this service, nicknamed e-mail, are also offering such added services as a hookup of the subscriber’s personal computer to the Telex network and a two-hour delivery of letter-quality documents to many parts of the country. They have all discovered that electronic mail alone cannot at this stage attract enough customers to stem the tide of red ink.

Electronic mail allows a message to be typed into a personal computer or a terminal and then transmitted variously through cable, telephone-cum-modem, or satellite link to a receiving personal computer or terminal. One of its alleged advantages is the so-called store and forward message. A user may send messages at any time and, unlike a telephone connection, e-mail does not require the recipient to be on the other end of the line. Then again, the old-fashioned postal service does not require that the recipient be there at the time of delivery either.

When all is said and done, electronic mail is no more efficient, in the vast majority of cases, than the telephone or the postal service it is supposed to replace. Nor does it have the flexibility to be able to deliver packages such as spare parts, in the manner of another innovation, the overnight express service pioneered by Federal Express.

In addition, electronic mail faces the problem of compatibility that has plagued the entire personal computer industry since its inception. At the moment, there are about a dozen services, among them MCI Mail, Western Union’s EasyLink, the ITT Corporation’s Dialcom and General Electric’s Quick-Comm – none of which can be linked with any of the others.

The situation is comparable to there being a dozen different postal services, any one of which may or may not be capable of delivering a message to the particular company for which it is intended. Before even sending the message, a company has to determine whether it can indeed be delivered.

The problem is compounded by the fact that there is no e-mail central. Nor is there any universal directory of subscribers to the different services to help a business determine which potential recipient of its electronic letter subscribes to which service. For now, electronic mail’s solution to the dilemma seems to be the hybrid half e-mail, half regular mail represented by MCI’s now familiar orange envelopes.

Chances are that before a universal e-mail network is ever developed, the whole idea of electronic mail, along with those of teletext and videotex, will have been reduced to the span of a few specialized applications. As a general means of information exchange, the concepts are technologically intriguing. But they are economically naive and, more importantly, no more convenient than the existing alternatives.•