The defense of Big Tech’s dubious tax dodge over the past week by Apple CEO Tim Cook and Google’s Eric Schmidt has been a maddening exercise in intellectual dishonesty. The premise of these two (and much of the tech world) is this: If you want us to pay our fair share than change your system so that we can’t exploit the loopholes. You know, don’t blame us for pursuing our self-interests; make it impossible for us to do so. Of course, what’s left unsaid is that Apple and Google and other behemoths have endless boatloads of cash to hire lobbyists who’ll make sure that any attempt at leveling the tax plane is as difficult as can be. That’s how the loopholes initially came into being.

The opening of “Future Shlock,” Evgeny Morozov’s powerful big-tech takedown in the New Republic, which draws parallels between the 19th-century advent of the sewing machine and today’s so-called world-flattening gadgets:

“The sewing machine was the smartphone of the nineteenth century. Just skim through the promotional materials of the leading sewing-machine manufacturers of that distant era and you will notice the many similarities with our own lofty, dizzy discourse. The catalog from Willcox & Gibbs, the Apple of its day, in 1864, includes glowing testimonials from a number of reverends thrilled by the civilizing powers of the new machine. One calls it a ‘Christian institution’; another celebrates its usefulness in his missionary efforts in Syria; a third, after praising it as an ‘honest machine,’ expresses his hope that ;every man and woman who owns one will take pattern from it, in principle and duty.’ The brochure from Singer in 1880—modestly titled ‘Genius Rewarded: or, the Story of the Sewing Machine’—takes such rhetoric even further, presenting the sewing machine as the ultimate platform for spreading American culture. The machine’s appeal is universal and its impact is revolutionary. Even its marketing is pure poetry:

On every sea are floating the Singer Machines; along every road pressed by the foot of civilized man this tireless ally of the world’s great sisterhood is going upon its errand of helpfulness. Its cheering tune is understood no less by the sturdy German matron than by the slender Japanese maiden; it sings as intelligibly to the flaxen-haired Russian peasant girl as to the dark-eyed Mexican Señorita. It needs no interpreter, whether it sings amidst the snows of Canada or upon the pampas of Paraguay; the Hindoo mother and the Chicago maiden are to-night making the self-same stitch; the untiring feet of Ireland’s fair-skinned Nora are driving the same treadle with the tiny understandings of China’s tawny daughter; and thus American machines, American brains, and American money are bringing the women of the whole world into one universal kinship and sisterhood.

‘American Machines, American Brains, and American Money’ would make a fine subtitle for The New Digital Age, the breathless new book by Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman, and Jared Cohen, the director of Google Ideas, an institutional oddity known as a think/do-tank. Schmidt and Cohen are full of the same aspirations—globalism, humanitarianism, cosmopolitanism—that informed the Singer brochure. Alas, they are not as keen on poetry. The book’s language is a weird mixture of the deadpan optimism of Soviet propaganda (‘More Innovation, More Opportunity’ is the subtitle of a typical sub-chapter) and the faux cosmopolitanism of The Economist (are you familiar with shanzhai, sakoku, or gacaca?).

There is a thesis of sorts in Schmidt and Cohen’s book. It is that, while the ‘end of history’ is still imminent, we need first to get fully interconnected, preferably with smartphones. ‘The best thing anyone can do to improve the quality of life around the world is to drive connectivity and technological opportunity.’ Digitization is like a nicer, friendlier version of privatization: as the authors remind us, ‘when given the access, the people will do the rest.’ ‘The rest,’ presumably, means becoming secular, Westernized, and democratically minded. And, of course, more entrepreneurial: learning how to disrupt, to innovate, to strategize. (If you ever wondered what the gospel of modernization theory sounds like translated into Siliconese, this book is for you.) Connectivity, it seems, can cure all of modernity’s problems. Fearing neither globalization nor digitization, Schmidt and Cohen enthuse over the coming days when you ‘might retain a lawyer from one continent and use a Realtor from another.’ Those worried about lost jobs and lower wages are simply in denial about ‘true’ progress and innovation. ‘Globalization’s critics will decry this erosion of local monopolies,’ they write, ‘but it should be embraced, because this is how our societies will move forward and continue to innovate.’ Free trade has finally found two eloquent defenders.

___________________________

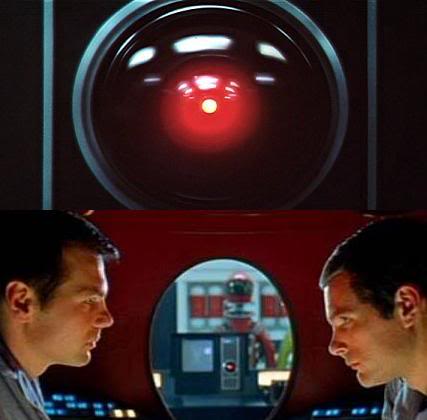

“What is the opposite of a Genius Bar?”: