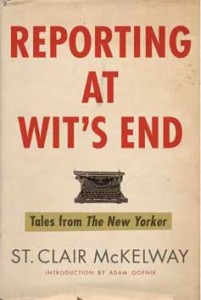

"Reporting at Wit's End," a thick paperback collection of great McKelway reportage is currently on sale at Amazon for $7.20.

A New Yorker writer for decades, St. Clair McKelway (1905-1980) had an insatiable appetite for criminals of all kinds–impostors, embezzlers, counterfeiters, etc.–and the law-enforcement personnel who tried to bring them to justice. In recent decades, McKelway has been more of a cult favorite than a legend like Liebling or Mitchell, but hopefully the 2010 paperback collection of his work, Reporting at Wit’s End, will remedy that situation.

It was the counterfeiter category that gave McKelway the raw material for his most famous article, a 1949 piece entitled, “Mister 880,” about an elderly paperhanger who used a hand cranked printing press to manufacture barely passable duplicates of one dollar bills. Despite being a crappy counterfeiter, Mister 880 frustrated the Feds for a decade and was the unlikely target of a massive manhunt, before a series of flukish events brought him down. An excerpt from the opening of that piece (which was also adapted for film):

“In the late summer of 1938, an elderly widower named Edward Mueller found that he was in need of money for the support of his dog and himself. He was a man of simple tastes, and the dog was an undemanding mongrel terrier. Mr. Mueller had for many years been a superintendent in apartment buildings on the Upper East Side. Living in the basements of these buildings, he and his wife had raised two children, a boy and a girl. By the time Mrs. Mueller died, in 1937, the children had grown up and gone off to homes of their own. The son had a job and was doing well; the daughter had married. After the death of his wife, Mueller moved out of the basement that had been their home together and rented a small, sunny flat on the top floor of the brownstone tenement near Broadway and Ninety-sixth Street. He and the dog took possession of it in the spring of 1938. Feeling that he was too old to be a superintendent any longer, Mueller tried for a while to make a living as a junkman. He was sixty-three at the time and was gentle, sweet-tempered, and strongly independent. Only five feet three inches tall, he had a lean, hard-muscled frame, a healthy pink face. bright blue eyes, a shiny bald dome, a fringe of snowy hair over his ears, a wispy white mustache and hardly any teeth. He bought a pushcart secondhand and, accompanied by his dog, roamed the neighborhood when the weather was good, picking up junk in vacant lots and along the river front under the West Side Highway. He went about his work in a leisurely manner and always looked happy. Sometimes he stopped to talk to strangers who wanted to talk, and at other times he carried on fragmentary, one-sided conversations with the dog that trotted at his heels. He was able to sell some of the odds and ends he picked up to the wholesale junk dealers, but before many months had gone by, he began to realize that he wasn’t making enough to live on, and that if he didn’t do better his savings would soon be gone and he would be destitute.

When his son and daughter visited him, and when he went to see them, Mueller said that he was getting along all right and didn’t need a thing. For a full half century, he had depended only on himself, and he had the flinty pride on an elderly man who had worked hard since he was a boy of thirteen and had never asked helped from anybody. The life he had lived had been a respectable and law-abiding one. Everybody who had ever known Mueller would have said that he was probably the last man in the world to try to make money dishonestly. That was exactly what Mueller did, however. In November, 1938, he became a counterfeiter of one dollar bills.”

When his son and daughter visited him, and when he went to see them, Mueller said that he was getting along all right and didn’t need a thing. For a full half century, he had depended only on himself, and he had the flinty pride on an elderly man who had worked hard since he was a boy of thirteen and had never asked helped from anybody. The life he had lived had been a respectable and law-abiding one. Everybody who had ever known Mueller would have said that he was probably the last man in the world to try to make money dishonestly. That was exactly what Mueller did, however. In November, 1938, he became a counterfeiter of one dollar bills.”