You might be soothed knowing that the mid-1960s’ fear that automation would cause widespread, imminent technological unemployment didn’t come to pass, but the worry may have been more premature than preposterous, more of a battle won in a war that’s ultimately unwinnable. In a riposte to a 1965 Fortune article written by Charles E. Silberman which derided the powers of computing, Edmund C. Berkeley, editor of Computers and Automation, argued that the future, with literate machines and driverless automobiles, would eventually arrive. We’re much closer to that tomorrow today. The opening:

In the 1965 issue of Fortune, Charles E. Silberman, in his article, “The Real News About Automation,” advances an interesting position. He states:

“Employment of manufacturing production workers has increased by one million in the last 3 1/2 years…This turn-around in blue-collar employment raises fundamental questions about the speed with which machines are replacing men…Automation has made substantially less headway in the United States than the literature on the subject suggests…No fully automated process exists for any major product in the U.S….Many people writing about automation…have grossly exaggerated the economic impact of automation…In their eagerness to demonstrate that the apocalypse is at hand, the new technocratic Jeremiahs…show a remarkable lack of interest in getting the details straight, and so have constructed elaborate theories on surprisingly shaky foundations…The view that computers are causing mass unemployment has gained currency largely because of a historical coincidence: the computer happened to come into widespread use in a period of sluggish economic growth and high unemployment…Full automation is far further in the future because ‘there is no substitute for the brewmaster’s nose’…Man’s versatility was never really appreciated until engineers and scientists tried to teach computers to read handwriting, recognize colors, translate foreign languages, or respond to vocal commands..We don’t have enough experience with automation to make any firm generalizations about how technology will change the structure of occupations…” and in essence he asserts that vast unemployment due to automation is not to be expected.

__________________

There are a number of important defects in Silberman’s argument, enough to make the whole argument unsound.

In the first place, Silberman makes a considerable point of the fact that he has investigated a number of situations where a large degree of automation was reported, and he has observed that a much smaller degree of automation was actually to be found there. For example he has found men still at work personally guiding the movement of engine blocks from one automated machine to another. From these instances he concludes that the threat of automation in producing unemployment has been grossly exaggerated.

Basically, this is the argument that because something has not happened yet, it is not going to happen. Of course, as soon as we express the argument in this form, it is obviously not true. I am reminded of what was being said about automatic computers in the early 1950’s by hardheaded business men: the machines would never be reliable enough or versatile enough to do any substantial quantity of useful business work.

Second, Silberman refers to man’s versatility, reading of handwriting, responding to vocal commands, etc. You will notice that he does not mention what would have been mentioned in this sentence if said some 15 years ago: “man’s uniquely human ability to think, to solve problems, to play games, to create”–because now it is abundantly clear that these abilities are being shared by the computer, the programmed automatic computer.

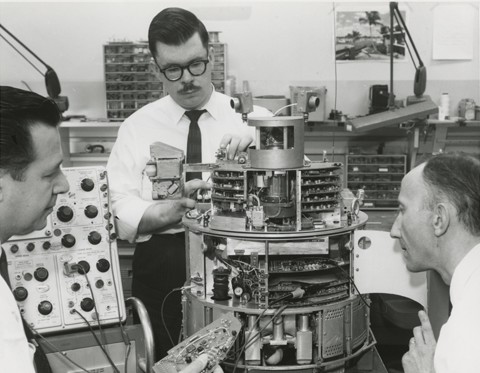

But the versatility area also of man’s capacities is rapidly being “threatened” by the computer, by such devices as the programmable optical reader, in which a computer applies clever programs to deciphering the precise nature of certain kinds of marks and thereby identifies them. A programmable film reader made by a firm in Cambridge, Mass., is able to read film at a speed 5000 times the rate that a human being can read it.

To assert that because of man’s versatility, the computer will not be able to compete with man is a silly argument, because there are no logical, scientific, or technological barriers to this accomplishment. Silberman asserts there will be a cost barrier: It may be many years before a computer can economically displace the human driver of a school bus at the rate of $4 an hour. But developments in microminiature, chemically-grown, circuits are so amazing, that we can look forward to the time when a programmed computer equal to the brains of most men can be produced for say $1000 apiece. Certainly there is nothing magical or supernatural about the brain of a man; and certainly once the process of chemically growing brains is understood, much better materials than protoplasm can be found for making them.

Third, even if “no fully automated process exists for any major product in the United States” at the present time, is there really very much difference between a process which used to require 100 men and now requires 5 or 3, compared with a process which used to require 100 men and now requires zero?•