The two best-selling novels in America during the 19th-century (not counting the Bible) were likely Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. The latter was written by Lew Wallace, a lawyer, diplomat and Union General who became most known as a man of letters. He was also, notably, forceful in the area of race relations, arguing against the color line in college football. There weren’t many Americans like him then nor are there now. The opening of his obituary in the February 16, 1905 edition of the New York Times:

“Crawfordsville, Ind.–Gen. Lew Wallace, author, formerly American Minister to Turkey, and veteran of the Mexican and Civil Wars, died at his home in this city to-night, aged seventy-eight years.

The health of Gen. Wallace has been failing for several years, and for months it has been known that his vigorous constitution could not much longer withstand the ravages of a wasting disease.

For more than a year he has been unable to properly assimilate food, and this, together with his advanced age, made more difficult his fight against death. At no time ever has he confessed his belief that the end was near, and his rugged constitution and remarkable vitality have done much to prolong his life.

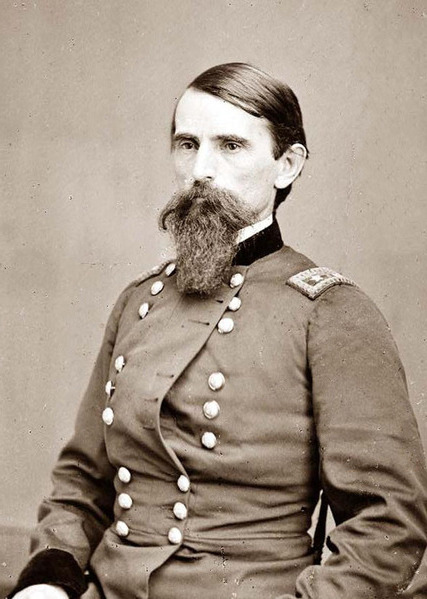

Gen. Lew Wallace, who years ago achieved widespread distinction as a lawyer, legislator, soldier, author, and diplomat, was a man of exceptionally refined manner, broad culture, and imposing personal appearance. He was a son of David Wallace, who was elected Governor of Indiana by the Whigs in 1837. His birthplace was Brooksville, Franklin County, Ind., where he was born April 10, 1827.

Although Gen. Wallace was famous as a soldier long before he entered the field of letters, it was through his authorship of Ben-Hur and several other popular works that he became known to the largest number of people. Ben-Hur was dramatized eighteen years after the publication of the book, the sale of which in Canada, England, and Continental Europe, as well as in the United States, was tremendous.

Although Gen. Wallace was famous as a soldier long before he entered the field of letters, it was through his authorship of Ben-Hur and several other popular works that he became known to the largest number of people. Ben-Hur was dramatized eighteen years after the publication of the book, the sale of which in Canada, England, and Continental Europe, as well as in the United States, was tremendous.

As a boy Lew Wallace was a keen lover of books, and his father’s possession of a large library afforded him an opportunity to become acquainted with much of the best literature of the time. From his mother he inherited a love of painting and drawing, but these instincts were overpowered by his desire for a more active life. His mother died when he was only ten years old, and from that time on he refused to submit patiently to restraint. An effort was made to send him to the town school. It was only partially successful. Later his father put him in college at Crawfordsville, but his stay there was brief.

At an early age he commenced the study of law, receiving valuable instruction from his father, and at the end of four years was admitted to the bar. He used to say that the law was the most detestable of all human occupations. It was said that he was unable to prepare a case, but when it came to trial he accepted the statements of his partner as to the law and the evidence and then, following his own convictions to the merits of the case, made an appeal which rarely failed to be effective.”