At the Financial Times, David Runciman has an article about Political Order and Political Decay, Francis Fukuyama’s follow-up to 2012’s The Origins of Political Order. The political scientist thinks America made sequential mistakes, establishing democracy ahead of a strong central government, and is paying for these and other sins. Few would argue the country isn’t currently in a political quagmire, but I think historical sequence may not be the most important factor. America by design is a disparate nation, an experiment in multitudes, and there will always by divisions. We ebb and flow, but the flows are pretty spectacular. And while the writer is correct to assert that too much of America’s power has fallen under the control of too few, you could say the same of the late 19th century, and that was remedied for a long spell. A passage about Fukuyama’s prescription for proper political order:

“Fukuyama’s analysis provides a neat checklist for assessing the political health of the world’s rising powers. India, for instance, thanks to its colonial history, has the rule of law (albeit bureaucratic and inefficient) and democratic accountability (albeit chaotic and cumbersome) but the authority of its central state is relatively weak (something Narendra Modi is trying to change). Two out of three isn’t bad, but it’s far from being a done deal. China, by contrast, thanks to its own history as an imperial power, has a strong central state (dating back thousands of years) but relatively weak legal and democratic accountability. Its score is more like one and a half out of three, though it has the advantage that the sequence is the right way round were it to choose to democratise. Fukuyama doesn’t say if it will or it won’t – the present signs are not encouraging – but the possibility remains open.

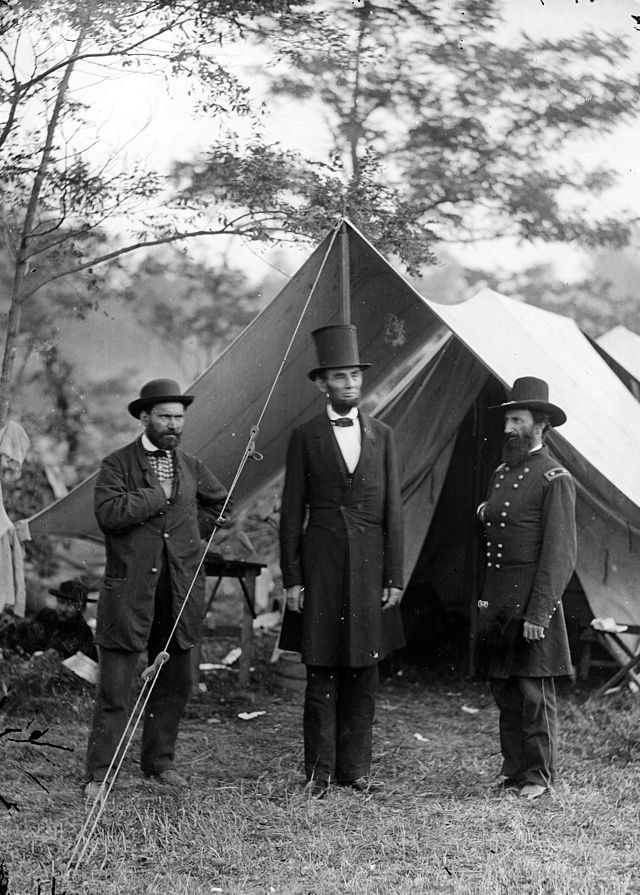

The really interesting case study, however, is the US. America’s success over the past 200 years bucks the trend of Fukuyama’s story because the sequence was wrong: the country was a democracy long before it had a central state with any real authority. It took a civil war to change that, plus decades of hard-fought reform. Among the heroes of Fukuyama’s book are the late-19th and early-20th-century American progressives who dragged the US into the modern age by giving it a workable bureaucracy, tax system and federal infrastructure. On this account, Teddy Roosevelt is as much the father of his nation as Washington or Lincoln.

But even this story doesn’t have a happy ending. Just as it can take a major shock to achieve political order, so in the absence of shocks a well-ordered political society can get stuck. That is what has happened to the US. In the long peace since the end of the second world war (and the shorter but deeper peace since the end of the cold war), American society has drifted back towards a condition of relative ungovernability. Its historic faults have come back to haunt it. American politics is what Fukuyama calls a system of ‘courts and parties’: legal and democratic redress are valued more than administrative competence. Without some external trigger to reinvigorate state power (war with China?), partisanship and legalistic wrangling will continue to corrode it. Meanwhile, the US is also suffering the curse of all stable societies: capture by elites. Fukuyama’s ugly word for this is ‘repatrimonialisation.’ It means that small groups and networks – families, corporations, select universities – use their inside knowledge of how power works to work it to their own advantage. It might sound like social science jargon, but it’s all too real: if the next presidential election is Clinton v Bush again we’ll see it happening right before our eyes.”