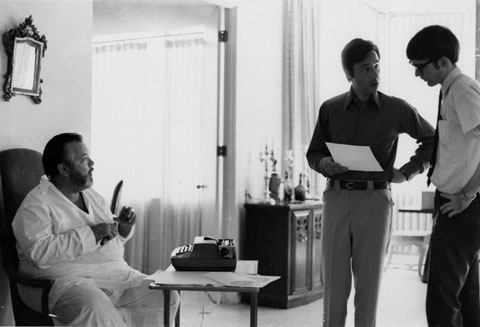

My blood boils at even the thought of Grey Gardens, that exercise in gawking and cruelty, but in the wider picture, Albert and David Maysles did amazing work. Gimme Shelter is one of the most perfect films I’ve ever watched, from its structure to its content, and Salesman, which just floors me, has never been timelier, with its depiction of the pawns left in the wake of the Disruption Machine. Albert, the remaining brother, passed away a couple weeks ago. Here’s a clip from the brothers’ 1963 film Orson Welles in Spain, in which the great and star-crossed director presages the fraying of the traditional studio picture, with its formality. The work he’s discussing turned out to be his uncompleted 1970s movie The Other Side of the Wind.

You are currently browsing articles tagged David Maysles.

Tags: Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Orson Welles

From the Maysles brothers’ 1963 film Orson Welles in Spain, a clip in which the great and star-crossed director presages the fraying of the traditional studio picture, with its formality. The work he’s discussing turned out to be his uncompleted 1970s movie The Other Side of the Wind.

Tags: Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Orson Welles

Creative destruction is an essential part of economic regeneration, as paradigms shift, structures change and tools develop. Fresh ideas challenge the accepted order, and emerging industries replace established ones. Simply put, it’s out with the old and in with the new. We’re experiencing it now as the information economy and digital communications ascend, disappearing other industries. But even if this process is best (and even necessary) for long-term solvency, what about those left behind in the shuffle, those dots on the graph who are made with red ink?

This situation, of course, is nothing new. Albert and David Maysles made this prickly transition period the crux of their breakthrough 1968 documentary, Salesman, which put a sad and human face on those who were moving as fast as they could while still being left behind. In vérité style, the filmmakers follow a crew of Massachusetts-based door-to-door bible salesmen who try to push handsomely illustrated books on working-class people who are struggling to feed the kids and pay the mortgage. By the late ’60s, itinerant peddling had reached obsolescence as enclosed malls became popular, people grew reluctant to open their doors for strangers and cars were so ubiquitous that no one needed the “store” to come to them. Additionally, religion and traditional values were losing their grip on the collective will of the people, so these sellers were up against it.

There are funny moments in cheap motels and in the modest, often shabby, homes they visit, but as one of the salesman, middle-aged Paul “The Badger” Brennan, struggles to keep his job and quell his frustrations, the movie develops into an American tragedy. Right before his eyes (and ours), Brennan’s way of life runs out of time before he does. As the regional managers berate the crew into producing bible sales that seem to grow scarcer by the day, the men have to fool themselves into not losing their religion. But Brennan, a wizened chain-smoker, can no longer manage the ruse. “If a guy’s not a success he’s got nothing to blame but hisself!” barks one of the bosses. But sometimes problems are more complex than that and the sweep of history wider.•

Jack Kroll of Newsweek interviews the Maysles:

Tags: Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Jack Krol, Paul "The Badger" Brennan