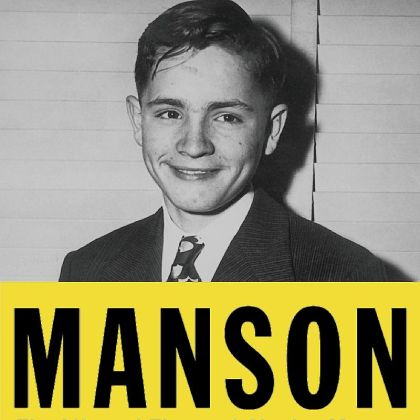

Kim Fowley is dead, and now they’re coming to take him away, ha-haaa! Such a bag of sleaze that he could make even record-industry professionals blanch, Fowley most famously formed and managed the teenage girl group the Runaways, and the nicest way to put it is that he certainly had an eye for young talent. The opening of David L. Ulin’s knowing 2013 Los Angeles Times review of Lord of Garbage, Fowley’s mental memoir:

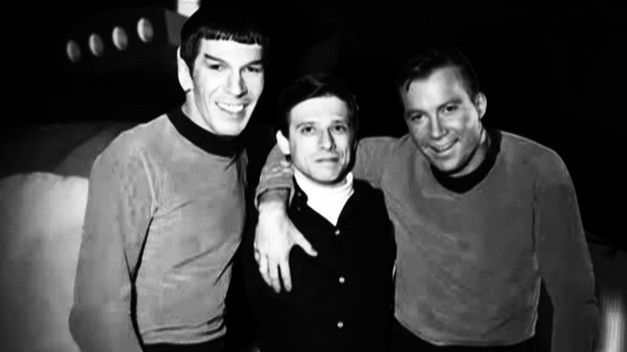

Kim Fowley came out of a Hollywood that doesn’t exist anymore, the Hollywood of Kenneth Anger and Ed Wood. Best known for cooking up the Runaways, he began to work in the music business in the late 1950s and since then has turned up in more places than Woody Allen’s Zelig, producing for Gene Vincent, writing with Warren Zevon and introducing John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band when they performed in Toronto in 1969.

Fowley turned 73 in 2012, and by his own admission has been suffering from bladder cancer, so it’s no surprise that he might choose this moment to look back. But his memoir, Lord of Garbage (Kicks Books: 150 pp., $13.95 paper) may be the weirdest rock ’n’ roll autobiography since … well, I can’t think of what.

The first of a projected three-volume set (Fowley claims the follow-ups have already been delivered), “Lord of Garbage” covers the first 30 years of its author’s life, from his early years bouncing between a model mother and a B-movie actor father, through a high school membership in the 1950s gang the Pagans and on to his involvement as a songwriter and producer in 1960s L.A.

How much of it is true is hard to say, exactly: Written in bombastic prose, it follows the broad parameters of Fowley’s biography while also insisting that, at the age of 1, his first words were: “I have a question. Why are you bigger than me?”

“Kim Fowley could talk at ten months,” he tells us, “could read and write by one and a half.” It’s no coincidence that he refers to himself in the third person, since Lord of Garbage is clearly the work of someone who considers himself larger than life. “You already know the genius music,” Fowley declares in a brief head note. “Now, know the genius man of letters.”

And yet, as self-congratulatory as that is, as sadly confrontational, it’s also, in its own weird way, slightly thrilling — not unlike Fowley himself.•