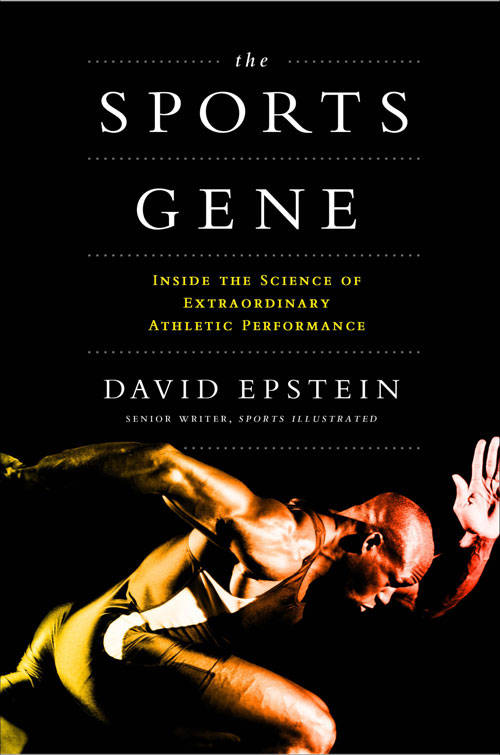

Was already circumspect of the idea that a level playing field in athletics was possible if we could just eliminate PEDs when I read David Epstein’s great 2014 book, The Sports Gene, which made plain how nature favors some over others, and not only in limb length and other obvious things but also in vision and blood and lungs. These inborn advantages laugh at the idea that 10,000 hours of practice can transform a modest talent into a champion, at least in sports (though I doubt 416 days at a piano in my wonder years was going to turn a tone deaf person like myself into a virtuoso).

In “Magic Blood and Carbon-Fiber Legs at the Brave New Olympics,” a Scientific American piece published just ahead of the Summer Games, Epstein again meditates on the subject. He poses a vital question: “We are long overdue to ask, openly and as a society, just what it is we want from sports. Is it to see superhumans doing superhuman things? Perhaps it is.”

The opening, which recalls the rare genetic mutation that helped Finnish skier Eero Mäntyranta become a virtually peerless cross-country competitor:

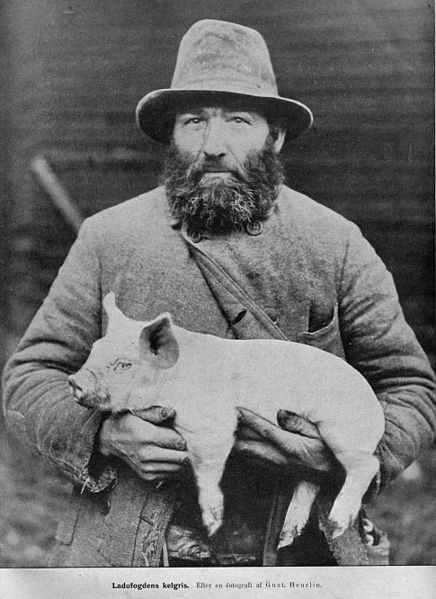

I knew Eero Mäntyranta had magic blood, but I hadn’t expected to see it in his face. I had tracked him down above the Arctic Circle in Finland where he was—what else?—a reindeer farmer.

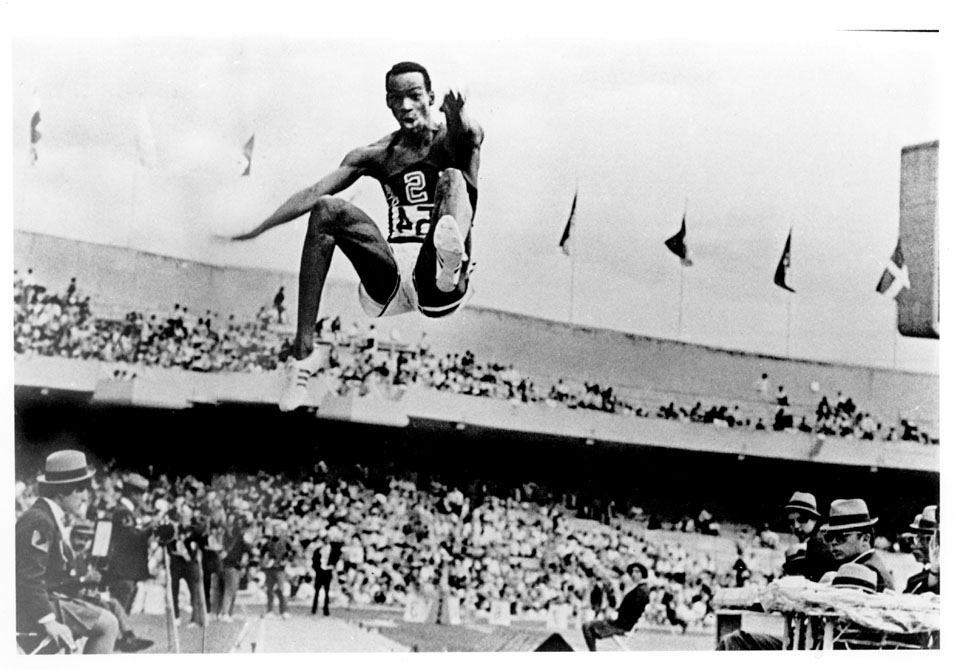

He was all red. Not just the crimson sweater with knitted reindeer crossing his belly, but his actual skin. It was cardinal dappled with violet, his nose a bulbous purple plum. In the pictures I’d seen of him in Sports Illustrated in the 1960s—when he’d won three Olympic gold medals in cross-country skiing—he was still white. But now, as an older man, his special blood had turned him red.

Mäntyranta, who passed away in late 2013, had a rare gene mutation that spurred his bone marrow to wildly overproduce red blood cells. Red cells convey oxygen to the muscles and the more you have, the better your endurance. That’s why some endurance athletes—most prominently Lance Armstrong—inject erythropoietin (EPO), the hormone that cues your bone marrow to produce red blood cells. Mäntyranta had about 50 percent more red blood cells than a normal man. If Armstrong had as many red blood cells as Mäntyranta, cycling rules would have barred him from even starting a race, unless he could prove it was a natural condition.

During his career, Mäntyranta was accused of doping after his high red blood cell count was discovered. Two decades after he retired Finnish scientists found his family’s mutation.•