In 1987, when Omni asked Bill Gates and Timothy Leary to predict the future of tech and Robert Heilbroner to speculate on the next phase of economics, David Byrne was asked to prognosticate about the arts two decades hence. It depends on how you parse certain words, but Byrne got a lot right–more channels, narrowcasting, etc. One thing I think he erred on is just how democratized it all would become. “I don’t think we’ll see the participatory art that so many people predict, Some people will use new equipment to make art, but they will be the same people who would have been making art anyway.” Kim and Snooki and cats at piano would not have been making art anyway. Certainly you can argue that reality television, home-made Youtube videos and fan fiction aren’t art in the traditional sense, but I would disagree. Reality TV and the such holds no interest for me on the granular level, but the decentralization of media, the unloosing of the cord, is as fascinating to me as anything right now. It’s art writ large, a paradigm shift we have never known before. It’s democracy. The excerpt:

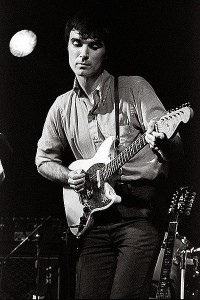

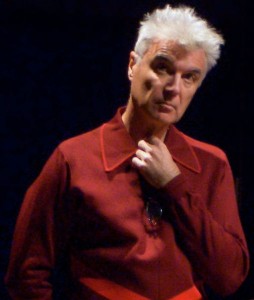

“David Byrne, Lead Singer, Talking Heads:

The line between so-called serious and popular art will blur even more than it already has because people’s altitudes are changing. When organized religion began to lose touch with new ideas and discoveries, it started failing to accomplish its purpose in people’s lives. More and more people will turn to the arts tor the kind of support and inspiration religion used to of- fer them. The large pop-art audience remains receptive to the serious content they’re not getting from religion. Eventually some new kind of formula — an equivalent of religion — will emerge and encompass art, physics, psychiatry, and genetic engineering without denying evolution or any of the possible cosmologies.

I think that people have exaggerated greatly the effects new technology has on the arts and on the number of people who will make art in the future. I realize that computers are in their infancy, but they’re pretty pathetic, and I’m not the only one who’s said that. Computers won’t take into account nuances or vagueness or presumptions or anything like intuition.

I don’t think computers will have any important effect on the arts in 2007. When it comes to the arts they’re just big or small adding machines. And if they can’t ‘think,’ that’s all they’ll ever be. They may help creative people with their bookkeeping, but they won’t help in the creative process.

The video revolution, however, will have some real impact on the arts in the next 20 years. It already has. Because people’s attention spans are getting shorter, more fiction and drama will be done on television, a perfect medium for them. But I don’t think anything will be wiped out; books will always be there; everything will find its place.

Outlets for art, in the marketplace and on television, will multiply and spread. Even the three big TV networks will feature looser, more specialized programming to appeal to special-interest groups. The networks will be freed from the need to try to please everybody, which they do now and inevitably end up with a show so stupid nobody likes it. Obviously this multiplication of outlets will benefit the arts.

I don’t think we’ll see the participatory art that so many people predict. Some people will use new equipment to make art, but they will be the same people who would have been making art anyway. Still, I definitely think that the general public will be interested in art that was once considered avant-garde.

I can’t stand the cult of personality in pop music. I don’t know if that will disappear in the next 20 years, but I hope we see a healthier balance between that phenomenon and the knowledge that being part of a community has its rewards as well.

I don’t think that global video and satellites will produce any global concept of community in the next 20 years, but people will have a greater awareness of their immediate communities. We will begin to notice the great artistic work going on out- side of the major cities — outside of New York, L.A., Paris, and London.”•

____________________________________

“Music and performance does not make any sense”: