MIT’s David Autor has bet the under on the Second Digital Age destroying jobs, though you might not agree these days if you invested your life savings in the value of a taxi medallion. He believes the short- and mid-term fears of the rise of the machines are unfounded and have crossed into hysteria. Time will tell, but he does acknowledge that the shifting of McJobs from high school juniors to those approaching senior citizen age is a downward spiral.

In conversation with Social Europe Editor-in-Chief Henning Meyer, Autor explains how two very different nations, Norway and Saudi Arabia, have taken vastly different approaches to abundance, a wonderful thing not always evenly distributed. What’s left unspoken is that the latter state has hidden beneath its vast wealth a quiet epidemic of poverty.

An excerpt:

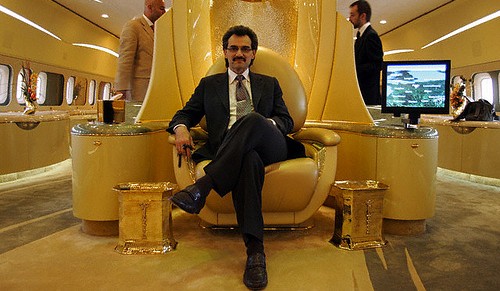

Take, for example, two countries: Norway and Saudi Arabia. Both of them have huge amounts of sovereign wealth. You could say it’s like they have a machine that creates wealth for them. It’s not a computer, it’s just oil, but that’s okay; it creates surplus. You could say, “In those countries, maybe no-one needs to do anything, because they just have so much money,” but Norway and Saudi Arabia have handled this completely differently.

In Saudi Arabia only a little bit more than 10% of the private-sector workforce is Saudi, and the rest is guest workers. That is a recipe for long-term economic and social problems. In Norway just about everybody works, men and women, much more than most other European countries, but they don’t work that many hours. They have kept themselves relevant, and engaged, and prosperous, and actually pretty happy if you believe the data.

So, there are ways to deal with the challenge of abundance, but it’s not a bad problem to have on the scale of social problems that one could face. That’s what we’re talking about here, it’s the problem of abundance – in other words, abundant productivity, abundance of capability to do things with machines that we used to require human labour and toil for.

There are challenges that come with that. One is the leisure challenge; the other is, of course, some skills become less relevant faster than others. The people who have clearly been affected by the thrust of technological change, over the last 30 years especially, have been low-educated adults whose skills are more closely replaceable by automation, not actually necessary in the lowest-skilled jobs, but many have been displaced from middle-skilled jobs.

If I’m a clerical worker or a production worker and that type of work no longer exists, I can still do table waiting, I can still do security, I can still do cleaning, and actually I’ll probably displace an even less-educated worker who wanted that job. For example, in the US we see very few teenagers anymore working at so-called ‘teen’ jobs; they’re held by adults.

It does create challenges and they are distributional challenges.•