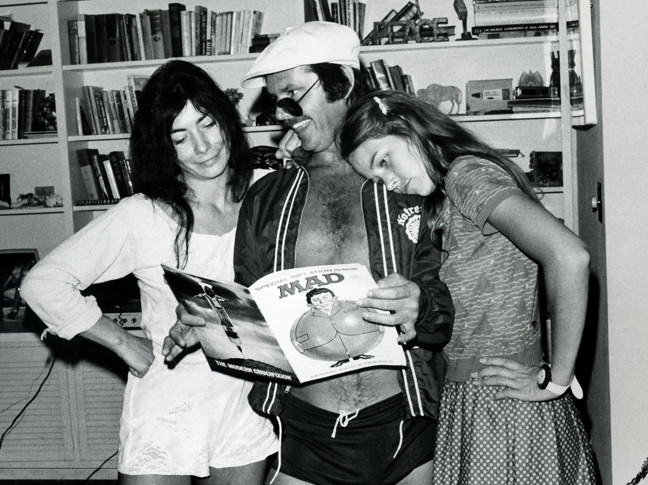

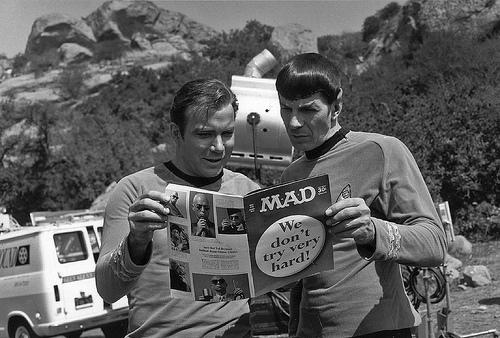

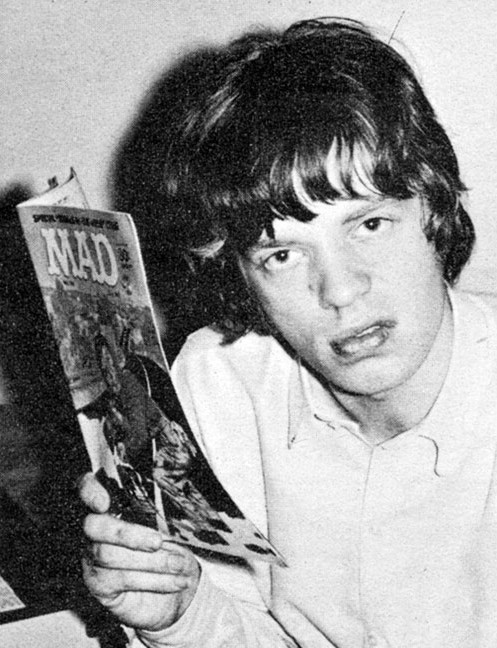

I know the Internet is freer, fuller and more democratic–and I love it–but I’m glad I was raised in a time of traditional magazines, an era approaching endgame in many essential ways. When I was a kid, I would go to used-magazine stores in Manhattan and trade in copies of a few of these for some of those, usually Mad for baseball or baseball for Mad, which introduced me to statistics and satire and so much more. Everything wasn’t at your fingertips, so you had to use your legs to get such backdated periodicals. What a genius invention–pages contained beneath a cover, hand-crafted and magical.

In a Los Angeles Review of Books article inspired by the recent implosion at The New Republic, David A. Bell succinctly sums up a time when the information flows, when home pages, like house organs, have arrived at obsolescence, when even online magazines–any magazines–seem to be beside the point. An excerpt:

“If the sheer economics of the digital age is not necessarily dooming the larger project that began in the 18th century, other elements of digital publication and politics have already fundamentally changed its nature. Most importantly, with the coming of social media and news aggregators, an increasing number of readers no longer interact with entire publications, or even large chunks of them. From the early 18th century to the late 20th, readers had only one way to read a magazine: they held the entire issue in their hands. They might only read a few articles, but they had all the others literally at their fingertips. Even in the early days of the internet, most online reading started with a visit to a website that put some or all of a magazine’s current articles on the same page, with links helpfully underlined. But today, more and more, readers encounter only the disjecta membra of publications that social media and aggregators have broken up. They no longer even visit the front page of a website. Although a dedicated reader of TNR until December, in recent years I rarely visited its website, instead relying on Twitter, Facebook, and RSS readers to bring me the magazine’s individual articles as they went live. And I read these articles alongside a host of others from publications I didn’t subscribe to, whose websites I never visited, and which in some cases I had never even heard of. But friends would post pieces on social media, or other articles would link to them. (I presume the same is true of the way many of you are reading this essay, right now.) Back in the days of print, once I paid for a magazine, I had an obvious material incentive to read everything in it, rather than go out and purchase something else. Now, most of the articles I read cost me nothing to access. All in all, I pay far less attention than I once did to where a particular article originally appeared; I rarely pause, like many other readers presumably, to consider how editors might have shaped it, behind the scenes. When I read a magazine on paper, on the other hand, its overall editorial project still imposes itself strongly on my reading response.

In this new digital universe where words have broken free of their traditional covers — and reading so easily turns into skimming — arguments flow faster and fiercer than ever, but they are atomized, and hyper-accelerated. A group of authors may momentarily coalesce to argue a particular point — the way commentators from Ta-Nehisi Coates to Corey Robin came together to say ‘good riddance’ to TNR. But then the molecules of argument break apart again in the constant flow. In this universe where unified magazines are dissolving, it is becoming far harder for a group of editors and writers to have the sort of durable influence that TNR acquired at moments in its past, notably in the 1980s. For all the excellent articles that the surviving weekly magazines still publish, their existence as distinct editorial projects jibes poorly with the way more and more of its readers actually read.”