Watson has a way with words and Siri sounds sexy, but Cyc is almost silent. Why so silent, Cyc?

Cycorp’s ambitious project to create the first true AI has been ongoing for 31 years, much of the time in seclusion. A 2014 Business Insider piece by Dylan Love marked the three-decade anniversary of the odd endeavor, summing up the not-so-modest goal this way: to “codify general human knowledge and common sense.” You know, that thing. Every robot and computer could then be fed the system to gain human-level understanding.

The path the company and its CEO Doug Lenat have chosen in pursuit of this goal is to painstakingly teach Cyc every grain of knowledge until the Sahara has been formed. Perhaps, however, it’s all a mirage. Because the work has been conducted largely in quarantine, there’s been little outside review of the “patient.” But even if this artificial-brain operation is a zero rather than a HAL 9000, a dream unfulfilled, it still says something fascinating about human beings.

An excerpt from “The Know-It-All Machine,” Clive Thompson’s really fun 2001 Lingua Franca cover story on the subject:

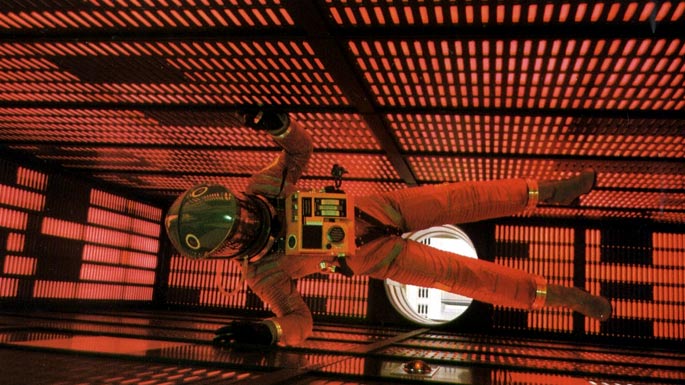

SINCE THIS is 2001, [Doug] Lenat has spent the year fielding jokes about HAL 9000, the fiendishly intelligent computer in Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. On one occasion, when television reporters came to film Cyc, they expected to see a tall, looming structure. But because Cyc doesn’t look like much—it’s just a database of facts and a collection of supporting software that can fit on a laptop—they were more interested in the company’s air conditioner. “It’s big and has all these blinking lights,” Lenat says with a laugh. “Afterwards, we even put a sign on it saying, CYC 2001, BETTER THAN HAL 9000.”

But for all Lenat’s joking, HAL is essentially his starting point for describing the challenges facing the creation of commonsense AI. He points to the moment in the film 2001 when HAL is turned on—and its first statement is “Good morning, Dr. Chandra, this is HAL. I’m ready for my first lesson.”

The problem, Lenat explains, is that for a computer to formulate sentences, it can’t be starting to learn. It needs to already possess a huge corpus of basic, everyday knowledge. It needs to know what a morning is; that a morning might be good or bad; that doctors are typically greeted by title and surname; even that we greet anyone at all. “There is just tons of implied knowledge in those two sentences,” he says.

This is the obstacle to knowledge acquisition: Intelligence isn’t just about how well you can reason; it’s also related to what you already know. In fact, the two are interdependent. “The more you know, the more and faster you can learn,” Lenat argued in his 1989 book, Building Large Knowledge-Based Systems, a sort of midterm report on Cyc. Yet the dismal inverse is also true: “If you don’t know very much to begin with, then you can’t learn much right away, and what you do learn you probably won’t learn quickly.”

This fundamental constraint has been one of the most frustrating hindrances in the history of AI. In the 1950s and 1960s, AI experts doing work on neural networks hoped to build self-organizing programs that would start almost from scratch and eventually grow to learn generalized knowledge. But by the 1970s, most researchers had concluded that learning was a hopelessly difficult problem, and were beginning to give up on the dream of a truly human, HAL-like program. “A lot of people got very discouraged,” admits John McCarthy, a pioneer in early AI. “Many of them just gave up.”

Undeterred, Lenat spent eight years of Ph.D. work—and his first few years as a professor at Stanford in the late 1970s and early 1980s—trying to craft programs that would autonomously “discover” new mathematical concepts, among other things. Meanwhile, most of his colleagues turned their attention to creating limited, task-specific systems that were programmed to “know” everything that was relevant to, say, monitoring and regulating elevator movement. But even the best of these expert systems are prone to what AI theorists call “brittleness”—they fail if they encounter unexpected information. In one famous example, an expert system for handling car loans issued a loan to an eighteen-year-old who claimed that he’d had twenty years of job experience. The software hadn’t been specifically programmed to check for this type of discrepancy and didn’t have the common sense to notice it on its own. “People kept banging their heads against this same brick wall of not having this common sense,” Lenat says.

By 1983, however, Lenat had become convinced that commonsense AI was possible—but only if someone were willing to bite the bullet and codify all common knowledge by brute force: sitting down and writing it out, fact by fact by fact. After conferring with MIT’s AI maven Marvin Minsky and Apple Computer’s high-tech thinker Alan Kay, Lenat estimated the project would take tens of millions of dollars and twenty years to complete.

“All my life, basically,” he admits. He’d be middle-aged by the time he could even figure out if he was going to fail. He estimated he had only between a 10 and 20 percent chance of success. “It was just barely doable,” he says.

But that slim chance was enough to capture the imagination of Admiral Bobby Inman, a former director of the National Security Agency and head of the Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation (MCC), an early high-tech consortium. (Inman became a national figure in 1994 when he withdrew as Bill Clinton’s appointee for secretary of defense, alleging a media conspiracy against him.) Inman invited Lenat to work at MCC and develop commonsense AI for the private sector. For Lenat, who had just divorced and whose tenure decision at Stanford had been postponed for a year, the offer was very appealing. He moved immediately to MCC in Austin, Texas, and Cyc was born.•