Steve Fainaru and Mark Fainaru-Wada, who’ve done brilliant work (here and here) on the NFL’s existential concussion problem and yet still somehow are passionate Niners fans, have written an excellent ESPN The Magazine piece about Chris Borland, the football player who retired after his rookie season to safeguard his health.

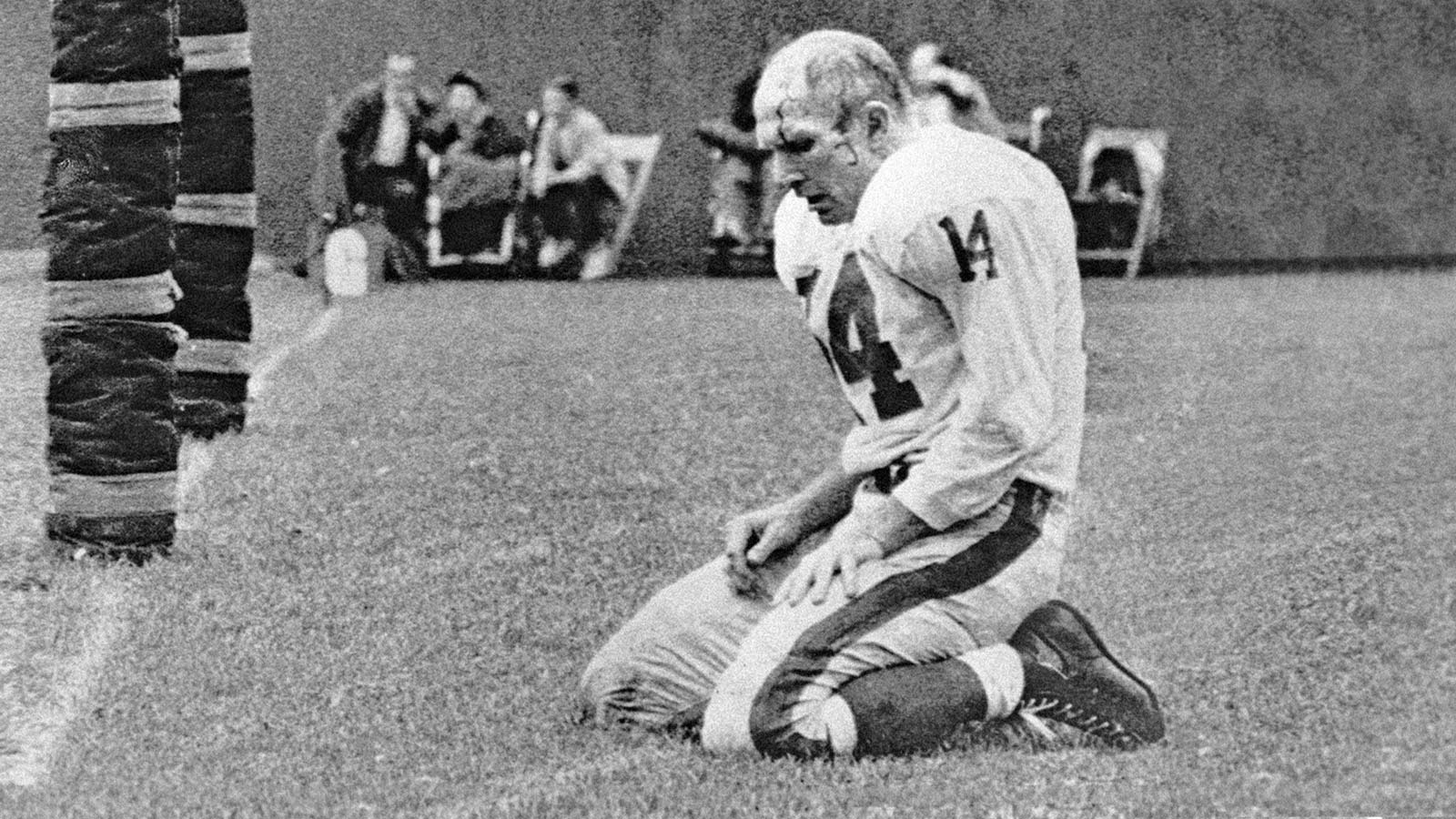

The former San Francisco linebacker’s preemptive attempt at self-preservation was a shot across the bow, a shocking move the league hadn’t experienced since the 1960s, when so-called Hippie players voluntarily left the game and its militaristic nature during Vietnam Era. Borland’s decision made news, as you might expect, and he became something of a reluctant political football.

The ESPN article reveals the NFL’s response to Borland’s decision was, well, NFL-like: tone-deaf, corporate and petty. Although he’d left the game, the former player was asked to take a “random” drug test almost immediately. It seems the league wanted to deflate his stance and prove he retired to avoid detection over illegal substances. Unless it was a remarkable coincidence, the NFL hoped to paint Borland a fraud and thereby negate his very valid concerns.

There’s no way humans can safely play football. No helmet can preserve a head from whiplash–in fact the modern one is a weapon that increases the occurrences. People who profit from the sport can make believe otherwise, but there’s no way out but down. Borland and others who’ve made a quick exit, and the stalwarts who’ve awakened to the game’s toll, have underlined that reality.

An excerpt:

Borland has consistently described his retirement as a pre-emptive strike to (hopefully) preserve his mental health. “If there were no possibility of brain damage, I’d still be playing,” he says. But buried deeper in his message are ideas perhaps even more threatening to the NFL and our embattled national sport. It’s not just that Borland won’t play football anymore. He’s reluctant to even watch it, he now says, so disturbed is he by its inherent violence, the extreme measures that are required to stay on the field at the highest levels and the physical destruction he has witnessed to people he loves and admires — especially to their brains.

Borland has complicated, even tortured, feelings about football that grow deeper the more removed he is from the game. He still sees it as an exhilarating sport that cultivates discipline and teamwork and brings communities and families together. “I don’t dislike football,” he insists. “I love football.” At the same time, he has come to view it as a dehumanizing spectacle that debases both the people who play it and the people who watch it.

“Dehumanizing sounds so extreme, but when you’re fighting for a football at the bottom of the pile, it is kind of dehumanizing,” he said during a series of conversations over the spring and summer. “It’s like a spectacle of violence, for entertainment, and you’re the actors in it. You’re complicit in that: You put on the uniform. And it’s a trivial thing at its core. It’s make-believe, really. That’s the truth about it.”

How one person can reconcile such opposing views of football — as both cherished American tradition and trivial activity so violent that it strips away our humanity — is hard to see. Borland, 24, is still working it out. He wants to be respectful to friends who are still playing and former teammates and coaches, but he knows that, in many ways, he is the embodiment of the growing conflict over football, a role that he is improvising, sometimes painfully, as he goes along.•