“The use of animal manures to fertilize the land was considered by Alcott to be ‘disgusting in the extreme.'”

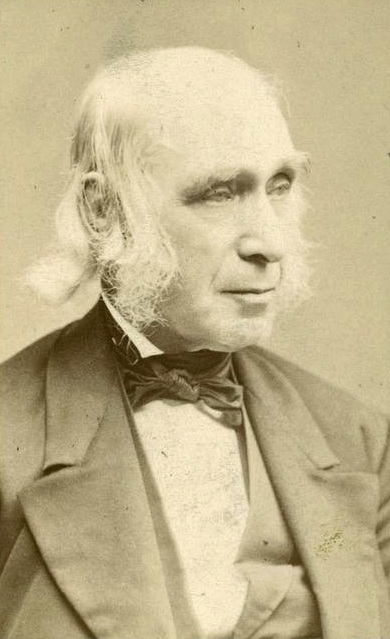

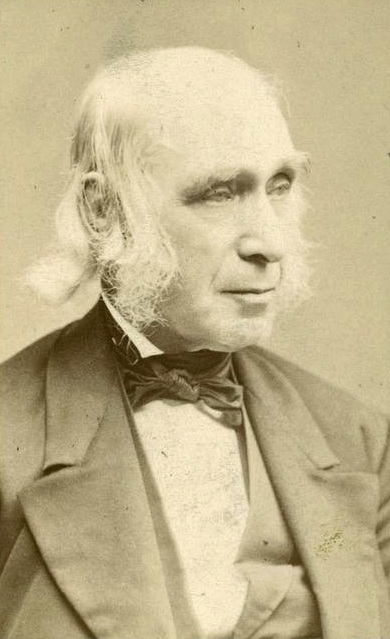

In 1843, Amos Bronson Alcott, Louisa May’s dad and a Transcendentalist and suffragist and abolitionist and animal rights activist, founded the commune known as “Fruitlands” in Massachusetts. He and a bevy of fellow non-farmers planned a small society that was to be safe alike for humans and animals–oh, and for John Palmer, a bearded man who refused to shave much to the consternation of the locals. It was to be a paradise of enlightenment and veganism a century before that latter word was even coined; but much like Brook Farm, it was a crashing financial failure and a dream soon abandoned. From an article in the July 25, 1915 New York Times:

“Alcott got his idea of the new Eden while visiting a group of English mystics headed by James Pierrepoint Greaves, a pupil of Pestalozzi, who had established a school according to the Concord philosopher’s teachings in Surrey, calling the place Alcott House. It was at this school that he met Charles Lane and H.C. Wright, and seems to have been fascinated by both men. Indeed, he writes home of the latter: ‘I am already knit to him with more than human ties, and must take him with me to America …or else abide here with him.’ Both returned with Alcott, and both joined him in establishing the New Eden. …

The scheme of life that underlay Fruitlands was simple. No ‘flesh,’ as the members called meat, was to be eaten. This prohibition included every animal product, such as milk, eggs, honey, butter, cheese. Moreover, they were to raise or to exchange for what could be raised in the neighborhood, all they used in a material way. No sugar, tea or coffee, neither silk nor wool for garments, were allowed. Linen was to be their raiment, for cotton, too, was tabooed. Tunics and trousers or brown liner clothed them fitly.

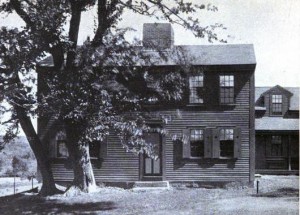

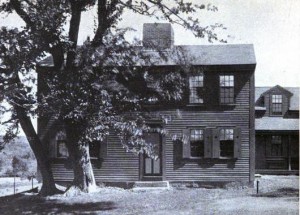

Not one of their number except Palmer seems to have had any notion of how to farm. Also, as Lane explains in a letter, ‘we are impressed with the conviction that by a faithful reliance on the Spirit which actuates us, we are sure of attaining to clear revelations of daily practical duties as they are to be daily done for us,’ wherefore no plan of work was laid out, and the various philosophers would wander vaguely about the fields, when the spirit hinted, sowing and digging, in some cases going over the same plot which one had scattered with clover seed to sow it again with rye, oats or barley. Two mulberry trees planted by them were put so close to the house that they almost heaved it free of its foundation in later years, though this misfortune was one that the community itself did not have to suffer.

The use of animal manures to fertilize the land was considered by Alcott to be ‘disgusting in the extreme,’ and was therefore prohibited. The idea was to plow under the growing green crops to achieve the required richness. The drawback to this being the difficulty of harvesting anything for themselves. But this did not as yet trouble them. What did trouble them was the unaccustomed toil with the spade, for they did not believe in using enslaved beasts to work for them, broke their backs and tore their hands. A compromise was achieved, and Old Palmer went off for a yoke of oxen to do the plowing. One of these proved to be a cow, and Palmer, to the horror of the rest, was seen to indulge in that creature’s yield of milk. He had, as he expressed it, ‘to be let down easy.’

The use of animal manures to fertilize the land was considered by Alcott to be ‘disgusting in the extreme,’ and was therefore prohibited. The idea was to plow under the growing green crops to achieve the required richness. The drawback to this being the difficulty of harvesting anything for themselves. But this did not as yet trouble them. What did trouble them was the unaccustomed toil with the spade, for they did not believe in using enslaved beasts to work for them, broke their backs and tore their hands. A compromise was achieved, and Old Palmer went off for a yoke of oxen to do the plowing. One of these proved to be a cow, and Palmer, to the horror of the rest, was seen to indulge in that creature’s yield of milk. He had, as he expressed it, ‘to be let down easy.’

There seem to have been other more spiritual concessions to this demand for an easier rule. The bread of the community was unbolted flour. In order to make it more palatable, Mr. Alcott, with something approximating humor, was accustomed to form the loaves ‘into the shapes of animals and other pleasing figures.’ Water was the sole drink, but it was invariably spoken of as their ‘beverage,’ probably with the same hope of making it appear more desirable. As for the meals, they are always spoken of as ‘chaste,’ the intercourse between the members at Fruitlands was ‘social communion,’ and sleep was a ‘report to sweet repose.’ If there is a power in words, and true sustenance, Fruitlands made the most of it.

Old Palmer’s life was one long fight to keep his beard, an appendage which Fruitlands alone, at the epoch, regarded with equanimity. In spite of the rage with which people generally regarded beards in those days, Palmer believed in them, and his life was a splendid assertion of this belief. Through all sorts of vicissitudes he hung on to that beard. Going to Boston he would be followed by hooting crowds. Men would spring out on him in his native Fitchburg from doorways, and endeavor to tear the offending thing from his face, but he could defend it, and did. Then he would be hauled to court for assault and battery, a fine imposed, on refusal to pay which Palmer would be sentenced to jail. There he remained at one time for over a year, part of it in solitary confinement. The jailers actually tried to shave him there, but the old man put up so fierce a fight that they desisted. Once the minister refused him Holy Communion, whereupon he strode to the altar and took the cup himself, asserting with flashing eyes that he ‘loved his Jesus as well as or better than any one else present.’ When at last he died he had his bearded face carved on his tombstone. where it may still be seen. When Fruitlands failed it was Palmer who bought the place, and there he carried on a queer sort of community of his own for more than twenty years.”