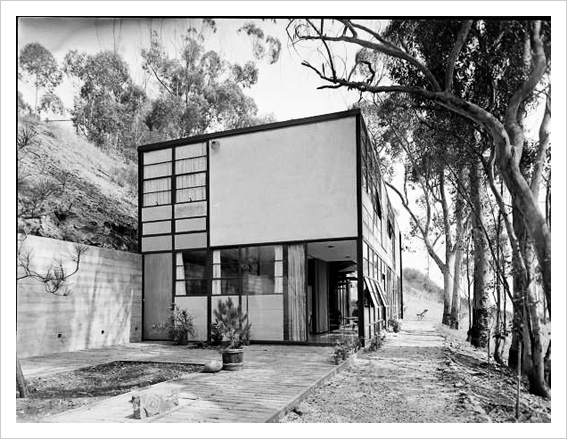

D.A. Pennebaker, Shirley Clarke and Albert Maysles captured the Khrushchev-era exhibition of American consumer goods that was held in Moscow in 1959, the Iron Curtain briefly lifted. On display was the handiwork of Charles Eames, Buckminster Fuller and many others. The Kitchen Debates between Nixon and his Soviet counterpart took place during this event.

You are currently browsing articles tagged Charles Eames.

Tags: Albert Maysles, Buckminster Fuller, Charles Eames, D.A. Pennebaker, Nikita Khrushchev, Richard M. Nixon, Shirley Clarke

This is very cool: A 1971 Life magazine report about a Manhattan computer expo in which IBMs wowed visitors by merely playing games of 20 Questions, no chess expertise even necessary. Better yet, the exhibition was curated by Charles Eames, who was as comfortable with computers as he was with furniture. From “A Lively Show with a Robot as the Star,” written by Fortune editor Walter McQuade:

“The stroller steps off the sidewalk and into the IBM display room on 57th Street in Manhattan and approaches one of the four shiny input typewriters of an IBM System 360 computer. The game is ’20 Questions.’ The computer ‘thinks up’ one of the 12 stock mystery words, like ‘duck,’ ‘orange,’ ‘cloud,’ ‘helium,’ ‘knowledge.’ The stroller has 20 chances to guess and if, perhaps, the mystery word is ‘knowledge,’ the typical conversation could start like this:

Stroller: ‘Does it grow?’

Computer: ‘To answer that question might be misleading.’

Stroller: ‘Can I eat it? Is it edible?’

Computer: ‘Only as food for thought.’

Stroller: ‘Do computers have it?’

Computer: ‘Strictly speaking, no.’

Twenty Questions is only the pièce de resistance in what is probably the canniest and most successful exhibition on computers ever devised. It should be: its deviser, the protean Charles Eames–poet, architect, painter, mathematician, toymaker, furniture designer and film maker–has had ample exposure at expos. Here, he and his collaborators reach back into the history and prehistory of computers to show how and why calculating machines came about.

Most of the story evolves on a gigantic, 48-foot, three-dimensional wall tapestry. Woven into it are hundreds of souvenirs from 1890 to 1950, the computer’s gestation period. Here are artifacts, documents and photographs, dramatizing six decades of striving, when information began to explode on the world and nobody knew quite what to do with the fallout.

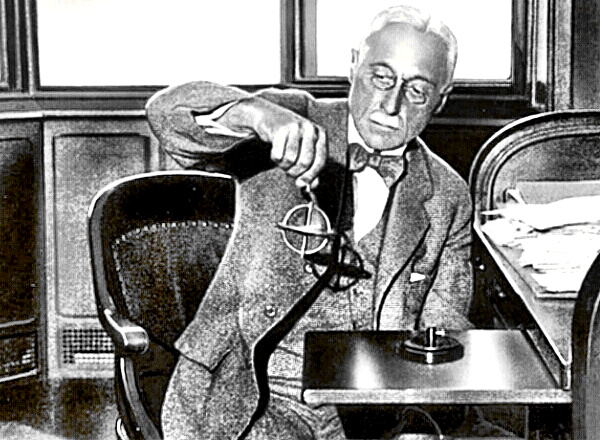

The devices range from ‘The Millionaire,’ one of the first calculators, made of brass, to Elmer Sperry’s gyroscope, to Vannevar Bush’s differential analyzer. Included are the work of such elegant minds as Alan Turing, Wallace Eckert, Norbert Wiener, John von Neumann. Even L. Frank Baum and his ‘clockwork copper man,’ Tik-Tok of Oz, is represented.

The military imperative to handle information quickly is underlined with a Norden bombsight and with ENIAC, an Army ballistics calculator and predecessor of UNIVAC. There are beautifully selected pieces of cultured debris to date it all; election literature in the years each of the Roosevelts ran for President, and one of the big old dollar bills, when they were worth 100 cents. Best of all are the evocations of mental battles fought and sometimes lost. Early in the century an English scientist, Lewis Fry Richardson, devoted many years to developing numerical models in which equations simulated physical systems to predict the weather. He was a dedicated visionary, but his widow wrote, ‘There came a time of heartbreak when those most interested in his ‘upper air’ research proved to be ‘poison gas’ experts. Lewis stopped his meteorological researches, destroying such as had not been published.

The wall closes with the birth of the UNIVAC in 1950. Since then the computer has progressed so fast, with computers working their own evolution, that the souvenirs would be just print-out sheets. But Eames demonstrates with models and film displays that if this be witchcraft, there are no witches involved–just the 350,000 full-time programmers (in the U.S. alone) and about two million other nonwitches who operate the machines; in a multiple, rapid-fire slidefilm; they chew gum, scratch themselves, dye their hair and do their work.

And when the stroller, no warlock himself, wanders in off the street with his family (it’s a great show for kids) and confronts the System 360, he is well advised to watch his language and frame his questions well. Eames’ finale to the exhibition can be fairly cheeky. System 360, Model 40, is not above printing out, in response to a muddled thought: ‘Your grammar has me stumped.'”

Tags: Charles Eames, Elmer Sperry, Walter McQuade

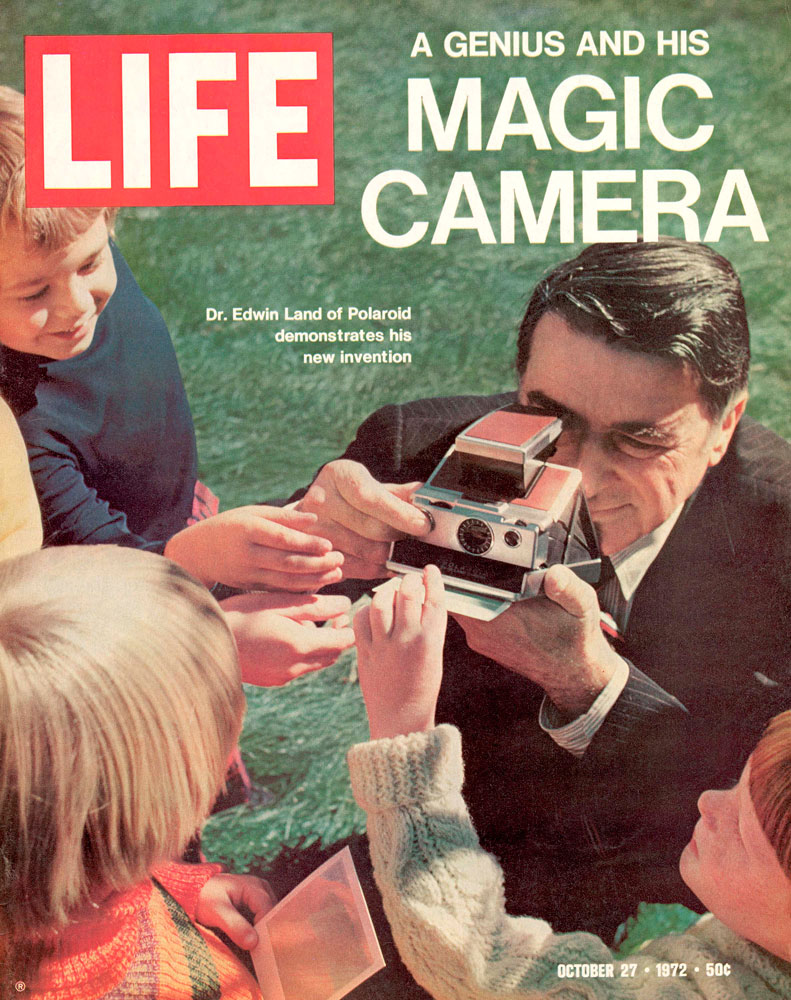

A beautiful Charles and Ray Eames long-form ad for the Polaroid SX-70, a great camera by Edwin Land. (Thanks Open Culture.)

Tags: Charles Eames, Edwin Land, Ray Eames

Tags: Charles Eames, Ray Eames

“IBM at the World’s Fair,” 1964:

“Tops,” 1969:

Tags: Charles Eames, Ray Eames

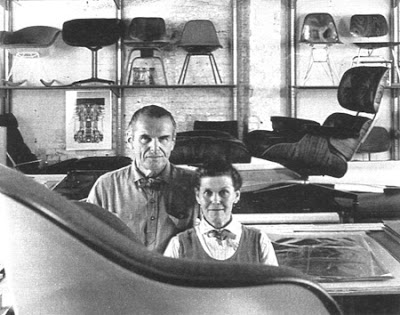

Ray and Charles Eames, that wonderful huband-and-wife design team, who were ahead of their time in understanding that industrial materials could be beautiful, also knew a thing or two about communications. Their 1953 short, “A Communications Primer.”

Tags: Charles Eames, Ray Eames

Two short films Ray and Charles Eames made for IBM during the 1950s:

“A Communications Primer,” 1953.

“The Information Machine,” 1956.

See also:

Tags: Charles Eames, Ray Eames

Cool short from 1956.

Tags: Charles Eames, Ray Eames

One of the first machines to convert solar power to electricty. If you’re going to do nothing, do it like this.

Tags: Charles Eames, Ray Eames

Tags: Arlene Francis, Charles Eames, Ray Eames