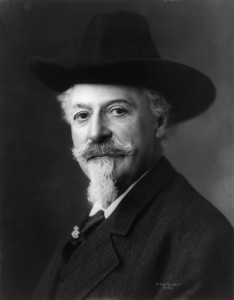

A 1917 clip of pioneer and entertainer Buffalo Bill Cody, with his unusual handshake. He realized early on that the Old West could be commodified.

You are currently browsing articles tagged Buffalo Bill Cody.

Tags: Buffalo Bill Cody

The aura of the American West was created and commodified long before there was a Hollywood, as traveling stage shows brought an appealing version of gunslinging to the masses. From Rob Walker’s 2007 Sunday Times Magazine article about how Buffalo Bill Cody packaged himself for the millions:

“While still a scout for the United States Army, Cody managed to hire himself out as a sort of celebrity hunting guide for well-to-do visitors to the American West. In 1869, when he was about 25, he impressed a writer calling himself Ned Buntline, who began a series of dime novels starring Buffalo Bill. These inspired a play, with Cody himself in the lead role. For the next several years, Cody switched off between actual scouting work in campaigns against Plains Indians — and appearing in plays with names like Scouts of the Plains.

But the great branding event of his career came in 1876, in the wake of George Custer’s disastrous defeat by Sioux Indians at Little Big Horn. Weeks later, Cody’s regiment engaged in a battle against a group of Cheyenne Indians, and Cody — there’s some disagreement on this — apparently killed one, obtaining what he pronounced ‘the first scalp for Custer.’ That fall, Cody starred in the play based on the incident. And by 1883, he and a couple of key collaborators — notably Nate Salsbury, a manager with wonderful showbiz instincts — had invented a show that ‘provided the template . . . for the early film western,’ Joy S. Kasson argues in her 2000 book Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory and Popular History. In the process, she writes, his Wild West ‘became America’s Wild West.’ Indeed, thanks to Salsbury, they actually copyrighted the phrase ‘Wild West’ (after a lengthy legal battle with rivals).

Live animals and blazing guns made the show more of a spectacle than a mere stage play. But a loose narrative and the vaguely educational content made it more respectable than a circus or a medicine show, and Salsbury kept gambling and drinking off the premises to attract the family demographic. At its height, the show included the sharpshooting of Annie Oakley, dramatic re-enactments of an Indian attack on the Deadwood stagecoach and a version of Little Big Horn. The organizers managed to include many actual Native Americans in the cast, including the Sioux chief Sitting Bull himself for part of its 1885 season.

Still, the authenticity was always balanced against affirmation: Cody’s arrival on the scene in the immediate aftermath of the re-enacted version of Little Big Horn converted a debacle into what felt like a victory. ‘It’s not really wild — that’s why it can be entertaining,’ Kasson, a professor of American studies at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, told me. ‘That’s where it leads to Hollywood: the idea that you can give people the feeling of danger, but it’s got to be basically tame.’ In several tours of Europe, the general theme of civilization triumphing over savagery went over well. (Indeed, Kasson cites the historian Richard White’s point that the Wild West shows essentially recast encroaching settlers as victims.) By the time Frederick Jackson Turner momentously declared that ‘the frontier has gone’ at the Columbian Exposition in 1893, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was in the midst of a monthslong stint right across the street; it was seen by an estimated six million people.”

••••••••••

Edison captured the pageantry of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show parade:

Another Buffalo Bill Cody post:

Tags: Buffalo Bill Cody, Rob Walker

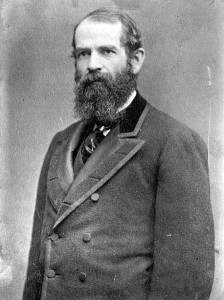

Financier Jay Gould, the groom's dad, was widely reviled. Some historians believe he was unjustly tarnished.

Having a father who’s a despised robber baron probably isn’t a lot of fun, even if he leaves you a bucketful of cash. Howard Gould, son of the late and hated financier and railroad tycoon Jay Gould, learned this the hard way when he married in 1898. The wedding ceremony, a lavish affair, was roundly mocked for its excess. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a paper that had been appropriately tough on the old man, came to the aid of the newlyweds, even predicting a long and happy union for the pair. Alas, it was not to be. The second article that’s excerpted, from New York’s Covington Sun a decade later, details the marriage’s bitter end, which involved Gould allegedly being cuckolded by the prominent soldier and nostalgia salesman Buffalo Bill Cody.

••••••••••

“Mr. Gould’s Marriage,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (October 13, 1898): “Howard Gould, son of Jay Gould, a famous millionaire, has married a woman who was at one time an actor. That fact does not justify the hubbaboo of print that has been made over it. Mr. Gould is a free man, being of age and a little over, therefore he may do as he pleases, if he does not break the law. His wedding was quiet and devoid of spectacle, so there was no occasion for the yellow journals to go into verbal convulsions over the waste of a fortune upon the unworthy cooks, waiters, florists, dressmakers, tailors, hosiers, wine merchants, carriage renters, musicians, jewelers, lapidaries and other people who commonly earn something when society gets married.

One interest in the case, however consists in the rumored sacrifice in half of his fortune that Mr. Gould has made in wedding Miss Clemmons. His father left a will which specified that if one of his children married without consent of the others, or his executors, he would lose half his patrimony and the lost half should be distributed among the other relatives. It is guessed that the young man has about $6,000,000, and if he were to lose half of this he would still be able to go to the circus once in a while and even buy pink lemonade. At all events, he married for love, and his life for that reason ought to be happy. So many of our children of millionaires marry pitiful creatures from Europe, for the sake of a title, that it is rather an agreeable surprise to find one of them who knows his own mind well enough to follow it and who has sufficient courage of his convictions to defy the efforts of the dead to rule the living.”

••••••••••

"Mrs. Gould, prior to the marriage, asserted that her relations with Colonel Cody were exclusively of a business nature, whereas they were meretricious."

“Sordid Troubles of the Married Rich,” Covington Sun (April 16, 1908): “That portion of the public which has been waiting so patiently for the oft-delayed washing of the family linen of the Howard Goulds is about to have its reward. Before Justice Dowling, Mrs. Gould’s attorney, Clarence J. Shearn, made a motion to have the issues framed for trial by jury on the ground that they were such a nature that no judge would care to pass on them first.

Sounding a note of self-pity as he surveyed the miserably unhappy life that he had led since he had married Katherine Clemmons, Howard Gould told of the many humiliations to which he had been subjected.

There are allegations of the deepest import to the wife of the millionaire, however, in the answer. Gould charged that not only before but after he married Katherine Clemmons she was guilty of improper conduct with Colonel William F. Cody (‘Buffalo Bill’). It was charged also that she became infatuated with Dustin Farnum, the actor; that she frequently had him in her apartment at the Hotel St. Regis; that she followed him on a tour through the New England States and visited him in his hotel after the performances.

There are charges of Mrs. Gould’s fondness for intoxicants, beginning, as alleged, with two or three cocktails before breakfast, a pint of Hock at luncheon, brandy highballs and unlimited champagne at dinner, whereby on one occasion, it is alleged, she fell from her chair to the floor.

Mr. Gould alleges that his marriage was the result of fraud and misrepresentation on the part of his wife. He says that Mrs. Gould, prior to the marriage, asserted that her relations with Colonel Cody were exclusively of a business nature, whereas they were meretricious. He swears that during 1887, 1889 and 1892 his present wife lived with Cody in London, Paris, Chicago, Nebraska, Virginia and New York.”

Tags: Buffalo Bill Cody, Clarence J. Shearn, Dustin Farnum, Howard Gould, Jay Gould, Justice Dowling, Katherine Clemmons

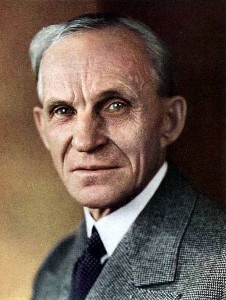

Henry Ford: This movie is an utter blowjob to my legacy, but it contains some fantastic footage of America from 1915-1930.

It was probably because he was close friends with Thomas Edison that Henry Ford became so interested in film. In his lifetime, the automotive magnate collected miles and miles of film footage that captured America in the early 20th century. The Ford Historical Film Collection (now housed at the National Archives) were used to create “Henry Ford’s Mirror of America,” an unobjective 35-minute piece of embarrassing pro-Ford propaganda that also happens to contain some amazing footage of the U.S. during the birth of the Industrial Revolution. Some highlights: a reunion of Civil War veterans (Blue and Gray) in Vicksburg in 1917, an Atlantic City hotel shaped like an elephant, the naturalist John Burroughs meeting his adoring public, Buffalo Bill Cody and his circus in action in 1916, women riveting in factories during WWI and the burial of the Unknown Soldier. Enjoy Part 1 and Part 2.