The day of the ransomware WannaCry attack, I wrote that a “world in which everything is a computer–even our brains–is a fraught one.” We live in a time when we hold what are essentially supercomputers in our hands, but more and more we’re in their grip. When the Internet of Things becomes the thing, linking all items and enabling them to incessantly collect information, pretty much everything from refrigerators to roads will be hackable. A permanent cat and (computer) mouse game will begin in earnest, and this time we’ll be inside the machine.

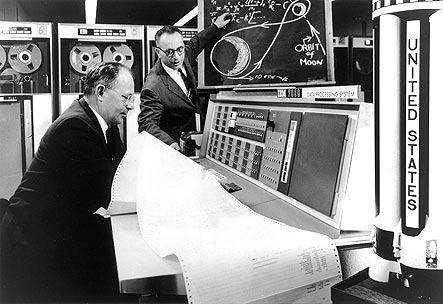

As Bruce Schneier writes in his wise and wary Washington Post essay on the subject: “Solutions aren’t easy and they’re not pretty.” An excerpt:

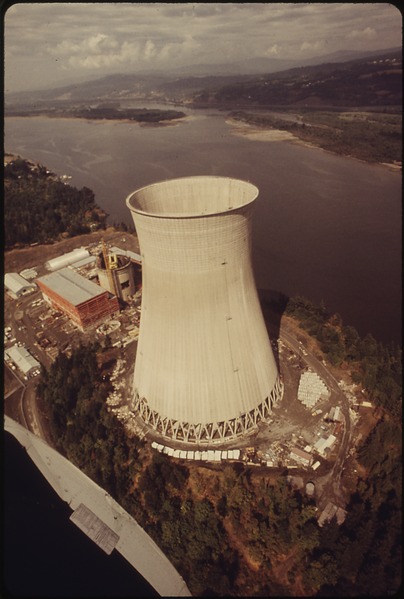

Everything is becoming a computer. Your microwave is a computer that makes things hot. Your refrigerator is a computer that keeps things cold. Your car and television, the traffic lights and signals in your city and our national power grid are all computers. This is the much-hyped Internet of Things (IoT). It’s coming, and it’s coming faster than you might think. And as these devices connect to the Internet, they become vulnerable to ransomware and other computer threats.

It’s only a matter of time before people get messages on their car screens saying that the engine has been disabled and it will cost $200 in bitcoin to turn it back on. Or a similar message on their phones about their Internet-enabled door lock: Pay $100 if you want to get into your house tonight. Or pay far more if they want their embedded heart defibrillator to keep working.

This isn’t just theoretical. Researchers have already demonstrated a ransomware attack against smart thermostats, which may sound like a nuisance at first but can cause serious property damage if it’s cold enough outside. If the device under attack has no screen, you’ll get the message on the smartphone app you control it from.•