Amid all the righteous rage over the avalanche of fake-news misinformation spread by Facebook, Twitter and Google in the run-up to Election Day, an idea by Larry Page from a 2013 conversation kept returning to me. It was reported by Nathan Ingraham of Verge:

Specifically, [Page] said that “not all change is good” and said that we need to build “mechanisms to allow experimentation.”

That’s when his response got really interesting. “There are many exciting things you could do that are illegal or not allowed by regulation,” Page said. “And that’s good, we don’t want to change the world. But maybe we can set aside a part of the world.” He likened this potential free-experimentation zone to Burning Man and said that we need “some safe places where we can try things and not have to deploy to the entire world.”•

The discrete part of the world the technologist is describing, an area which permits experiments with unpredictable and imprecise effects, already exists, and it’s called Silicon Valley. These ramifications do career around the world, and the consequences can be felt before they’re understood. As Page said, “not all change is good.”

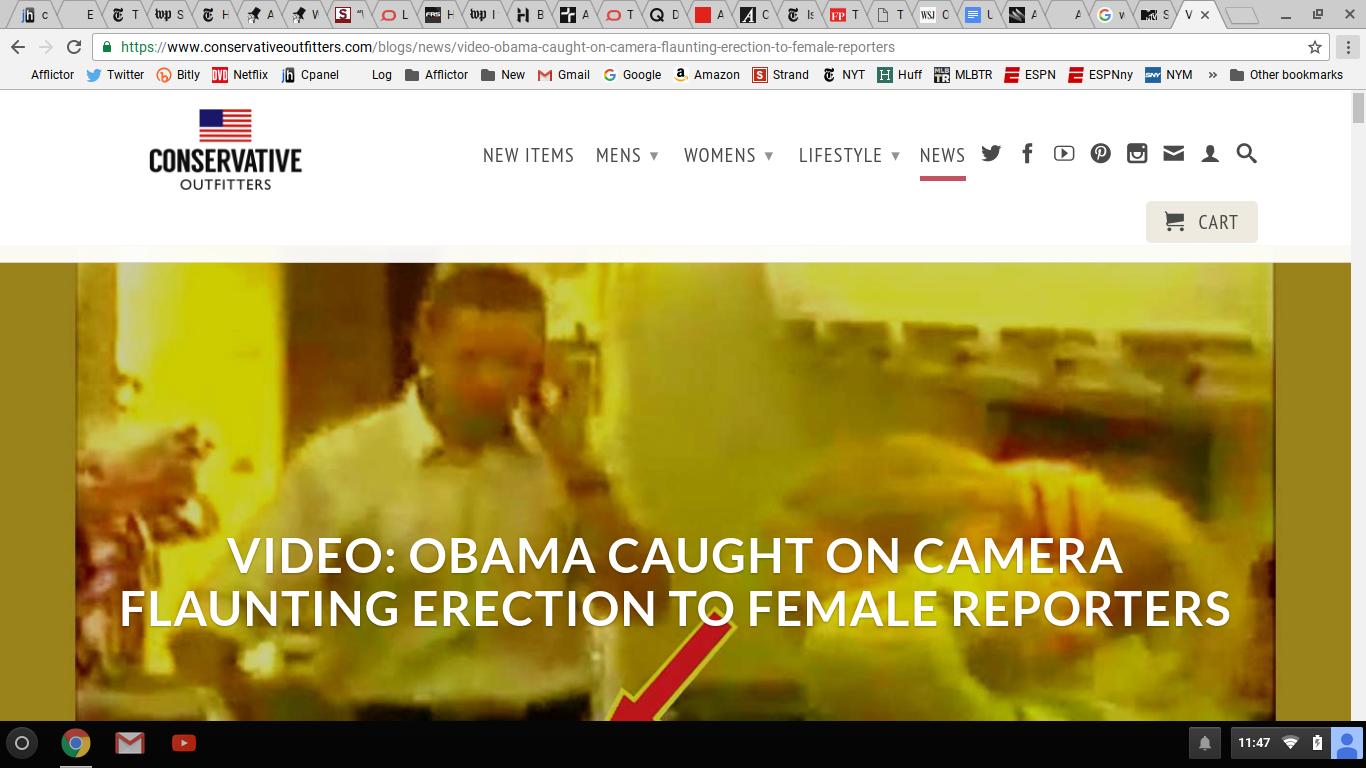

A brilliant analysis of the “wait, what?” vertigo of this Baba Booey of a campaign season can be found in “Shirtless Trump Saves Drowning Kitten,” an MTV News article by Brian Phillips, an erstwhile scribe at the late, lamented Grantland. “There has always been a heavy dose of unreality mixed into American reality,” the writer acknowledges, though the alt-right’s grim fairy tales being taken seriously and going viral is a new abnormal. Great communicators can no longer compete with those gifted at jamming the system. The opening:

Is anyone surprised that Mark Zuckerberg doesn’t feel responsible? One of the luxuries of power in Silicon Valley is the luxury to deny that your power exists. It wasn’t you, it was the algorithm. Facebook may have swallowed traditional media (on purpose), massively destabilized journalism (by accident), and facilitated the spread of misinformation on a colossal scale in the run-up to an election that was won by Donald Trump (ha! whoops). But that wasn’t Facebook’s fault! It was the user base, or else it was the platform, or else it was the nature of sharing in our increasingly connected world. It was whatever impersonal phrase will absolve Zuckerberg’s bland, drowsy appetite from blame for unsettling the things it consumes. In this way, the god-emperors of our smartphones form an instructive contrast with our president-elect: They are anti-charismatic. Unlike Trump, the agents of disruption would rather not be seen as disruptors. In the sharing economy, nothing gets distributed like guilt.

The argument that Facebook has no editorial responsibility for the content it shows its users is fatuous, because it rests on a definition of “editorial” that confuses an intention with a behavior. Editing isn’t a motive. It is something you do, not something you mean. If I publish a list of five articles, the order in which I arrange them is an editorial choice, whether I think of it that way or not. Facebook’s algorithm, which promotes some links over others and controls which links appear to which users, likewise reflects a series of editorial choices, and it is itself a bad choice, because it turns over the architecture of American information to a system that is infinitely scammable. I have my own issues with the New York Times, but when your all-powerful social network accidentally replaces newspapers with a cartel of Macedonian teens generating fake pro-Trump stories for money, then friend, you have made a mistake. It is time to consider pivoting toward a new vertical in the contrition space.•