I’m trying to remember the first time I heard about a startup hoping to sell “electronic newspapers,” a tabloid-sized device birthed by numerous sci-fi fantasies that would dynamically update as fresh reports were filed. Web 1.0? 2.0? I don’t know, but I recall these devices weren’t necessarily to be owned but were to be available on mass transit. I’m pretty sure the initial company I heard of endeavoring in this area was Japanese.

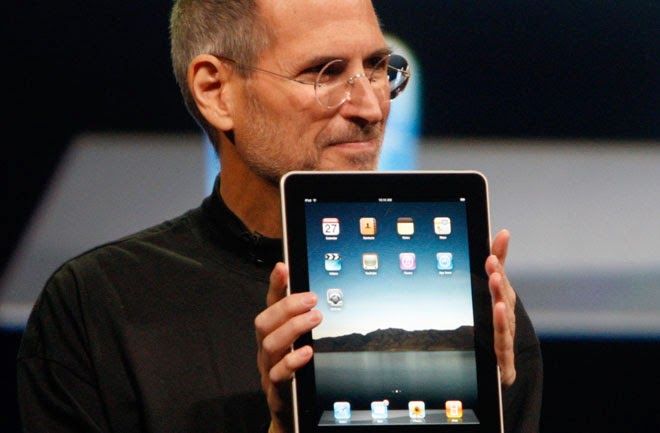

It’s all a retrofuture dream now, a fog of the recent past, as reality rushed by this alternate scenario, with tablets and, soon thereafter, smartphones, consigning it to the dustbin. Two years before the introduction of the iPad, an electronic newspaper plus, the vision still lived, its proponents unable to anticipate what was arriving. The opening of Eric A. Taub’s 2008 NYT report:

CAMBRIDGE, Massachusetts — The electronic newspaper, a large portable screen that is constantly updated with the latest news, has been a prop in science fiction for ages. It also figures in the dreams of newspaper publishers struggling with rising production and delivery costs, lower circulation and decreased ad revenue from their printed product.

While the dream device remains on the drawing board, Plastic Logic now has a version of an electronic newspaper reader: a lightweight plastic screen that mimics the look – but not the feel – of a printed newspaper.

The device uses the same technology as the Sony Reader and Amazon.com’s Kindle, a highly legible black-and-white display developed by E Ink. While both of those devices are intended primarily as book readers, Plastic Logic’s device, still unnamed in advance of its formal unveiling Monday at an emerging-technology trade show in San Diego, has a screen more than twice as large. The size of a piece of copier paper, it can be continually updated via a wireless link, and it can store and display hundreds of pages of newspapers, books and documents.

Richard Archuleta, chief executive of Plastic Logic, said the display was big enough to provide a layout like a newspaper’s. “Even though we have positioned this for business documents, newspapers is what everyone asks for,” Archuleta said.

The reader is to go on sale in the first half of next year.•

Long before Apple placed innovations cribbed from the Xerox Alto inside attractive, portable hardware, Alan Kay worked on the Dynabook, an “Intelligent Encyclopedia” tablet that had drawing and musical capacity. It wasn’t to be a newspaper really but more of a tool and a portable library. Stewart Brand wrote of the proposed invention in his seminal 1972 Rolling Stone article, “Space Wars: Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums”:

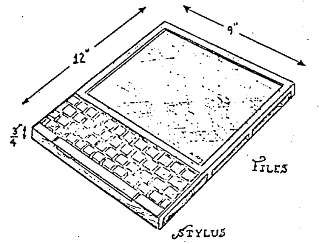

Alan is designing a hand-held stand-alone interactive-graphic computer (about the size, shape and diversity of a Whole Earth Catalog, electric) called “Dynabook.” It’s mostly high-resolution display screen, with a keyboard on the lower third and various cassette-loading slots, optional hook-up plugs, etc. His colleague Bill English describes the fantasy. thus:

It stores a couple of million characters of text and does all the text handling for you – editing, viewing, scanning, things of that nature. It’ll have a graphics capability which’ll let you make sketches, make drawings. Alan wants to incorporate music in it so you can use it for composing. It has the Smalltalk language capability which lets people program their own things very easily. We want to interface them with a tinker-toy kind of thing. And of course it plays Spacewar.”

The drawing capability is a program that Kay designed called “Paintbrush.” Working with a stylus on the display screen, you reach up and select a shape of brush, then move the brush over and pick up a shade of half-tone-screen you like, then paint with it. If you make a mistake, paint it out with “white.” The screen simultaneously displays the image you’re working on and a one-third reduction of it, where the dot pattern becomes a shaded half-tone.

A Dynabook could link up with other Dynabooks, with library facilities, with the telephone, and it could go and hide where a child hides. Alan is determined to keep the cost below $500 so that school systems could provide Dynabooks free out of their textbook budgets. If Xerox Corporation decides to go with the concept, the Dynabooks could be available in two or three years, but that’s up to Product Development, not Alan or the Research Center. Peter Deutsch comments: ‘Processors and memories are getting smaller and cheaper. Five years ago the idea of the Dynabook would have been a absolutely ridiculous. Now it merely seems difficult….”

And eventually the Dynabook was to break free of its casing and become ambient. From a Time piece in 2013:

Ninety-five percent of the Dynabook idea was a “service conception,” and five percent had to do with physical forms, of which only one — the slim notebook — is generally in the public view. (The other two were an extrapolated version of Ivan Sutherland’s head mounted display, and an extrapolated version of Nicholas Negroponte’s ideas about ubiquitous computers embedded and networked everywhere.)

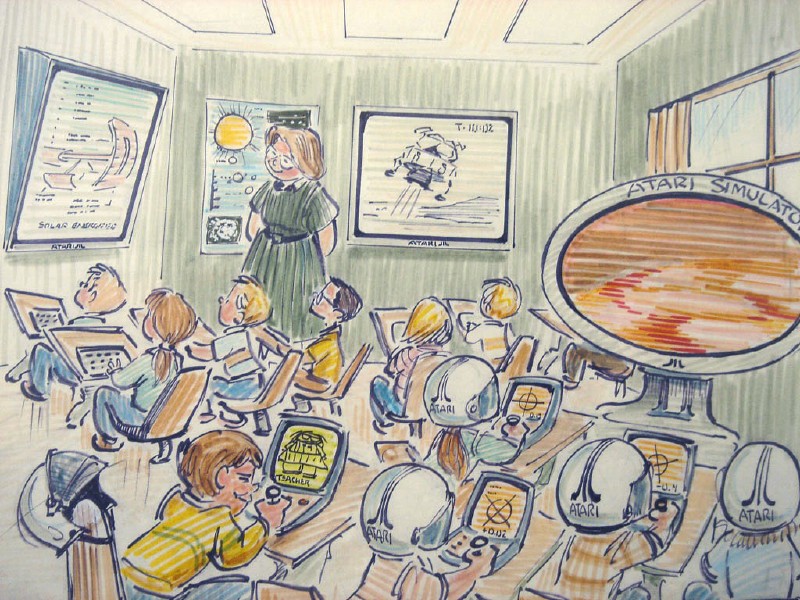

Kay never managed to get the proper funding to realize his ambition, and he was sorely disappointed by Jobs’ version. I bring this up because his machine is the subject of “The Atari Drawings: 1982,” a cool Medium article by computer pioneer Bob Stein, who sketched their shared futuristic vision when they worked together at the post-Bushnell version of the computer-game company. The author chides himself for not recognizing the importance of connectivity, although the “Space Wars” article makes it clear this aspect was always a potential use of the Dynabook. The brief opening (and one illustration):

In 1981 Alan Kay asked me to join him at Atari to continue my work on the idea of an Intelligent Encyclopedia. In order to explain what we were doing to the executives at Warner which owned Atari, I developed these scenarios of how the (future) encyclopedia might be used and commissioned Glenn Keane, a well-known Disney animator to render them. The most interesting thing for me today about these images is that although we foresaw that people would access information wirelessly (notice the little antenna on the device in the “tide pool” image, we completely missed the most important aspect of the network — that it was going to connect people to each other.