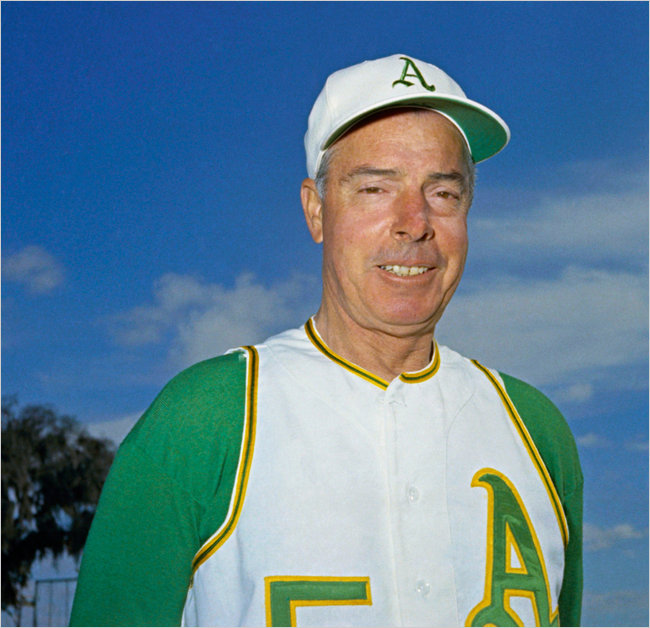

Even geniuses aren’t perfect: Billy Beane is the GM of the last-place Oakland A’s and Bill James Senior Advisor to the last-place Boston Red Sox, but they’re two of the pivotal figures in the development and popularization of Sabermetrics. In fact, James is likely the most influential of them all.

Of course, some bright people have the propensity to overthink things and outsmart themselves. For no real reason, Beane decided to trade affordable MVP candidate Josh Donaldson in the offseason for a couple of decent players and perhaps a great future shortstop, even though his team was built to compete now and playing in a very winnable division.

James’ sins haven’t been so slight, not just limited to puzzling player personnel decisions. He’s gone out of his way to defend Penn State football coach Joe Paterno, who clearly looked the other way while a pedophilia scandal was brewing right in front of his black glasses. In this case, James’ contrarian streak, which made him great, also laid him low.

The two figures had never appeared in public together until last week’s business-disruption conference hosted by NetSuite. Brian Costa of the Wall Street Journal gathered them and moderated a discussion about the future of Sabermetrics, etc. An excerpt:

WSJ:

Clearly, sabermetrics has improved the management of the game tremendously. How, if at all, has it made baseball a better game to watch?

Bill James:

I don’t know that it has, but we produce information, and information ties the fans to the game. People in a culture with no information about baseball have no interest in baseball. If you give people a little bit of information about baseball, they have a little bit of interest, and if you give them a lot of information about baseball, there’s the potential that they have a lot of interest. I’ve lived most of my life in the fans’ world and I see what I do as a fan’s activity. Granted, I work for the Red Sox. But I do know also that there are fans who go to sleep cursing my name.

Billy Beane:

It’s a different generation of fan that now has exposure and an interest in why things happen. Give them some rational reason for outcomes. We’re an information-hungry society, and one that is constantly trying to understand. I think there are a group of kids who love it for the numbers and love it for the information.

WSJ:

We’ve seen advances in particular areas of the game in recent years—pitch framing, defensive shifts—that are now better understood. What do you guys see as the aspect of the sport that is most in need of more research, more data and better understanding?

Billy Beane:

I’m jumping out of my chair on this one. It’s using analytics—and this sounds sort of non-field-related—but it’s injuries and medical. Even the healthcare industry is doing the same thing – trying to use big data to help solve healthcare. It’s the same in a simpler form for baseball or any sport and injuries. That’s the black swan for anyone involved in a baseball team—our injuries. Trying to predict them, minimize them, limit the downtime.•