“We need to put everything online,” Bill Joy tells Steven Levy in an excellent Backchannel interview, and I’m afraid that’s what we’re going to do. It’s an ominous statement in a mostly optimistic piece about the inventor’s advances in batteries, which could be a boon in creating clean energy.

Of course, Joy doesn’t mean his sentiment to be unnerving. He looks at sensors, cameras and computers achieving ubiquity as a means to help with logistics of urban life. But they’re also fascistic in the wrong hands–and eventually that’s where they’ll land. These tools can help the trains run on time, and they can also enable a Mussolini.

Progress and regress have always existed in the same moment, but these movements have become amplified as cheap, widely available tools have become far more powerful in our time. So we have widespread governmental and corporate surveillance of citizens, while individuals and militias are armed with weapons more powerful than anything the local police possesses. This seems to be where we’re headed in America: Everyone is armed in one way or another in a very dangerous game.

When Joy is questioned about the downsides of AI, he acknowledges “I don’t know how to slow the thing down.” No one really seems to.

An excerpt:

Steven Levy:

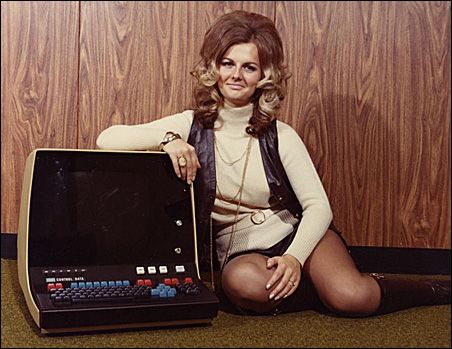

In the 1990s you were promoting a technology called Jini that anticipated mobile tech and the Internet of Things. Does the current progress reflect what you were thinking all those years ago?

Bill Joy:

Exactly. I have some slides from 25 years ago where I said, “Everyone’s going to be carrying around mobile devices.” I said, “They’re all going to be interconnected. And there are 50 million cars and trucks a year, and those are going to be computerized.” Those are the big things on the internet, right?

Steven Levy:

What’s next?

Bill Joy:

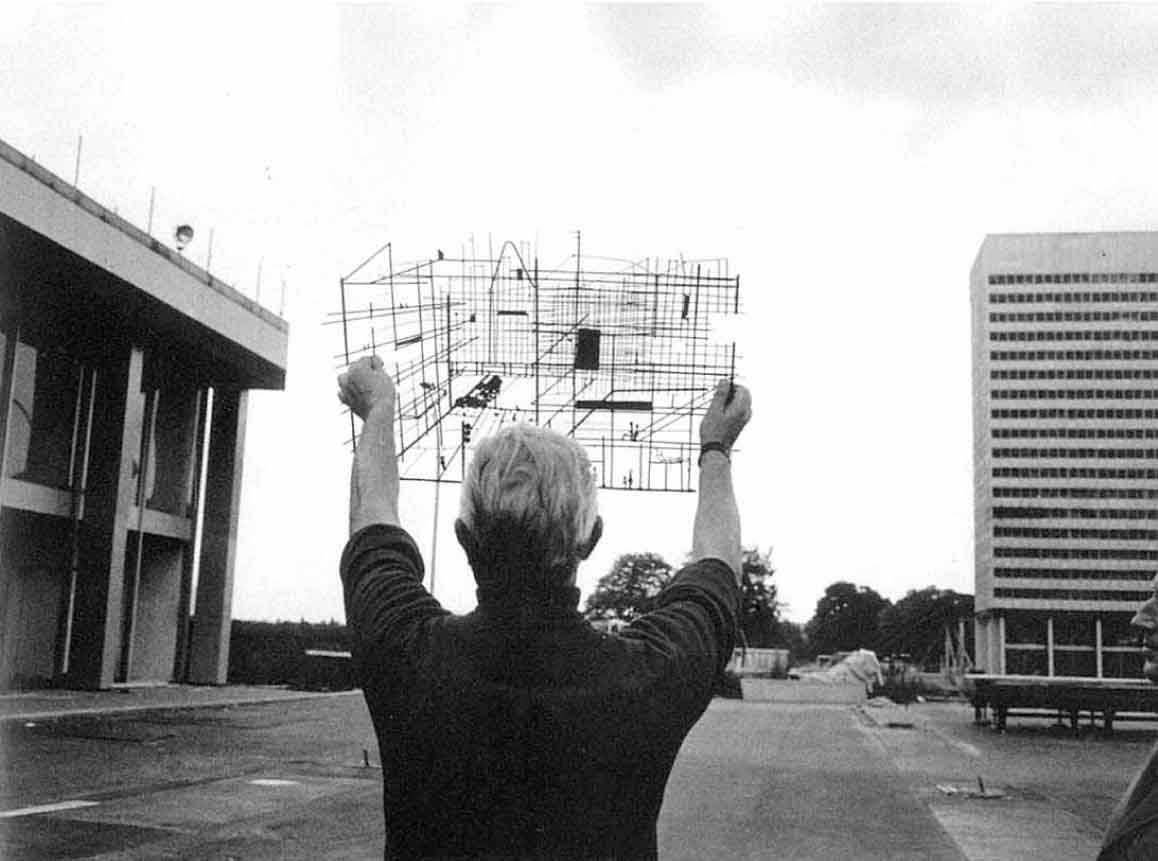

We’re heading toward the kind of environment that David Gelernter talked about in his book, Mirror Worlds, when he said, “The city becomes a simulation of itself.” It’s not so interesting just to identify what’s out there statically. What you want to do is have some notion of how that affects things in the time domain. We need to put everything online, with all the sensors and other things providing information, so we can move from static granular models to real simulations. It’s one thing to look at a traffic map that shows where the traffic is green and red. But that’s actually backward-looking. A simulation would tell me where it’s going to be green and where it’s going to be red.

This is where AI fits in. If I’m looking at the world I have to have a model of what’s out there, whether it’s trained in a neural net or something else. Sure, I can image-recognize a child and a ball on this sidewalk. The important thing is to recognize that, in a given time domain, they may run into the street, right? We’re starting to get the computing power to do a great demo of this. Whether it all hangs together is a whole other thing.

Steven Levy:

Which one of the big companies will tie it together?

Bill Joy:

Google seems to be in the lead, because they’ve been hiring these kind of people for so long. And if there’s a difficult problem, Larry [Page, Google’s CEO] wants to solve it. Microsoft has also hired a lot of people, as well as Facebook and even Amazon. In these early days, this requires an enormous amount of computing power. Having a really, really big computer is kind of like a time warp, in that you can do things that aren’t economical now but will be economically [feasible] maybe a decade from now. Those large companies have the resources to give someone like Demis [Hassabis, head of Google’s DeepMind AI division] $100 million, or even $500 million a year, for computer time, to allow him to do things that maybe will be done by your cell phone 10 years later.

Steven Levy:

Where do you weigh in on the controversy about whether AI is a threat to humanity?

Bill Joy:

Funny, I wrote about that a long time ago.

Steven Levy:

Yes, in your essay “The Future Doesn’t Need Us.” But where are you now on that?

Bill Joy:

I think at this point the really dangerous nanotech is genetic, because it’s compatible with our biology and therefore it can be contagious. With CRISPR-Cas9 and variants thereof, we have a tool that’s almost shockingly powerful. But there are clearly ethical risks and danger in AI. I’m at a distance from this, working on the clean-tech stuff. I don’t know how to slow the thing down, so I decided to spend my time trying to create the things we need as opposed to preventing [what threatens us]. I’m not fundamentally a politician. I’m better at inventing stuff than lobbying.•