There exists a band of far-flung thinkers who dream of humans repopulating and restoring the natural world via de-extinction (read here and here). It would be a regenesis, though it’s easier said than done. Even though such things aren’t currently doable, I wouldn’t say that they’re permanently impossible, not if we’re talking about the very long run. But we’re not likely digging ourselves out of our Anthropocene hole with such things.

In an excellent Five Books Interview on the topic of de-extinction, evolutionary biologist Beth Shapiro pours cold water on the reawakening of the woolly mammoth and other animals and birds that have bid the Earth adieu, pointing out not just the practical difficulties but also the ethical concerns. I’ve read two of the titles she chose, E.O. Wilson’s The Diversity of Life and Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction, both of which are certainly worth the time.

Before getting to her selections, the author of How to Clone a Mammoth explains exactly why we can’t do just that and why we shouldn’t even if we could. An excerpt:

Question:

If we were able to bring a mammoth back, what would the purpose of that be?

Beth Shapiro:

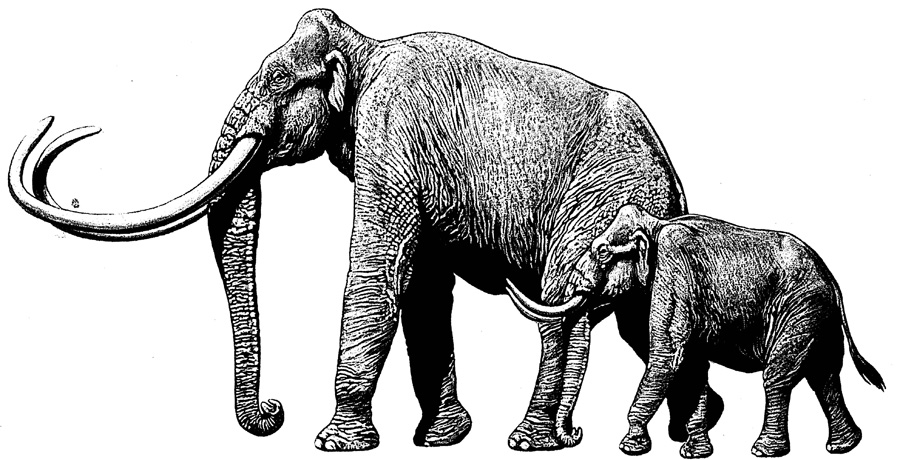

If we pretend, for a moment, that it’s technically possible – which it isn’t – and that it’s ethically ok – which it isn’t – why might we want to bring a mammoth back to life? Well, for me there are two reasons. The first is ecological. Elephants play a very important role in their ecosystem, they’re the biggest herbivore that exists. They wander around knocking down the big things and allow the habitat – the grasslands – to regenerate themselves. There’s no reason to suspect a mammoth wouldn’t have done the same thing.

There’s a Russian scientist called Sergey Zimov who has a park in North-Eastern Siberia called ‘Pleistocene Park‘. The Pleistocene was the geological interval that existed before the current one, which is the Holocene, sometimes the Anthropocene. It was the age of Ice Age Giants and he is preparing this park for the return of Ice Age Giants and so far he has bison and horses and five different species of deer. He doesn’t have mammoths yet, but he is making up for that using large road-rolling machinery. What he’s found in this Pleistocene Park of his is that where he has these grazing herbivores – bison, horses, deer – just by virtue of wandering around on the permafrost, digging up the soil, recycling nutrients, spreading the seeds around they have actually changed that habitat. They have reestablished the rich grasslands that used to be there during the time of these Ice Age Giants, creating the habitat that they themselves need to survive. Not only are these animals there and quite happy, but he’s also noted that things like saiga antelope have come to visit the park because there’s loads of stuff for them to eat there. He argues that giant herbivores are still a missing component that would really help to push this environment over the edge. There’s a potentially compelling ecological reason to bring mammoths back to life.

The next reason is more sentimental. Few of us are willing to imagine a world without elephants, but Asian elephants are endangered. Every year there are fewer of them. Their habitat is continuing to disappear as human populations grow. We’re having trouble stopping poachers taking them for their ivory. What if we could use this technology, this same swapping out of genes technology, not to bring a mammoth back to life, but to change an elephant a little bit so that it has some of the evolutionary adaptations that a mammoth had? Say, adaptations that allow it to survive somewhere cold. Elephants are a tropically adapted species, mammoths lived in the Arctic. If we could swap out some of the elephant gene and allow elephants to live in Europe, or Siberia, then we could create new habitat for elephants where they could survive while we tried to fix whatever mess is going on in their natural habitats. What if we could use this technology not to bring extinct species back to life but to save species that are alive today and yet in danger of becoming extinct because of changes to their habitat that are often caused by us?•