Ben Ehrenreich, a brilliant guy who is consumed by death, looked at the end of print in an electric age in his great 2011 essay, “The Death of the Book,” at the Los Angeles Review of Books. An excerpt:

“In 1962, Marshall McLuhan had published an almost spookily prescient book titled The Gutenberg Galaxy. It was, among other things, an extended critique of the culture of print. Technology shapes our consciousness, McLuhan argued, and the development of the printed book in the mid-fifteenth century had inaugurated a reorientation of human experience towards the visual, the regimented, the uniform and instrumental. Language, which had once been a wild, uncontainable affair between the oral and aural (think whisper, shout, and song, the playful market-square dynamism of dialect and argot) was silenced, flattened, squeezed into lines evenly arrayed across the rectilinear space between the margins. Spellings were standardized, vernaculars frozen into national languages policed by strict academies. Print, for McLuhan, was the driver behind all that we now recognize as modern. Through it nationalisms arose, and other horrors: capitalism, individualism, alienation. Time itself was emptied out—reduced, like the words on each page, to a linear sequence of homogeneous moments. Print had stolen something. Books had shrunk us. They had ‘denuded’ conscious life. ‘All experience is segmented and must be processed sequentially,’ McLuhan mourned. ‘Rich experience eludes the wretched mesh or sieve of our attention.’

An end was in sight. We had already entered a ‘new electric age’ characterized by interdependence rather than segmentation. ‘The world has become a computer,’ McLuhan wrote, ‘an electronic brain, exactly as in an infantile piece of science fiction.’ The Internet was still a Cold-War fantasy, but for McLuhan print’s corpse was already growing cold. (He dated the collapse of the Gutenberg Galaxy to 1905 and Einstein’s early work on relativity.) This was not necessarily cause for optimism. McLuhan coined the phrase ‘global village’ to describe the hyper-networked world that was already taking shape. He had no illusions, though, about the nobility of village life. Our newly TV-, telephone-, and radio-enwebbed multiverse could just as easily be ruled by ‘panic terrors … befitting a world of tribal drums’ as by any bright pastoral harmony. And so it was and is.”

In 1967, when Jacques Derrida took up the theme of ‘the end of the book’ in Of Grammatology, McLuhan’s ideas were still sufficiently in the air that the philosopher could refer to ‘this death of the civilization of the book of which so much is said’ without need for further explanation. But the ‘civilization of the book,’ for Derrida, meant more than the era of moveable type. It preceded Gutenberg, and even the medieval rationalists who wrote of ‘the book of nature’ and via that metaphor understood the material world as revelation analogous to scripture. The book for Derrida stood in for an entire metaphysics that reached back through all of Western thought: a conception of existence as a text that could be deciphered, a text with a stable meaning lodged somewhere outside of language. ‘The idea of the book is the idea of a totality,’ he wrote. ‘It is the encyclopedic protection of theology and of logocentrism against the disruption of writing, against its aphoristic energy and … against difference in general.’ Those, in case you couldn’t tell, are fighting words.”

••••••••••

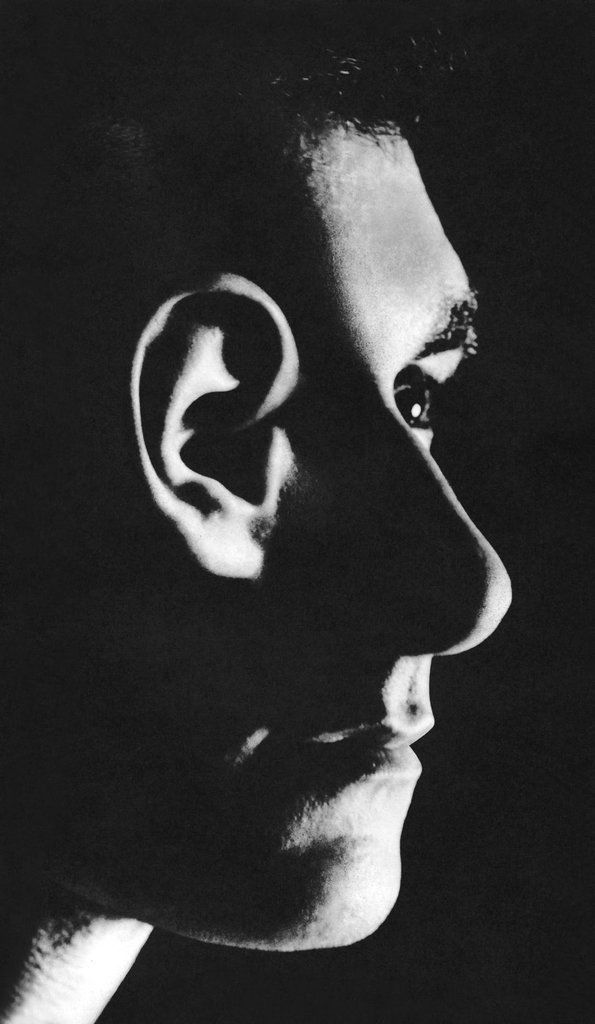

Dylan goes electric, Newport, 1965: