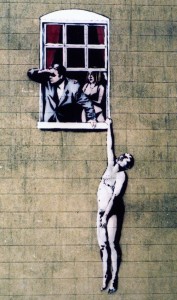

The perfect opening of “Banksy Was Here,” Lauren Collins’ excellent 2007 New Yorker article about the inscrutable artist:

“The British graffiti artist Banksy likes pizza, though his preference in toppings cannot be definitively ascertained. He has a gold tooth. He has a silver tooth. He has a silver earring. He’s an anarchist environmentalist who travels by chauffeured S.U.V. He was born in 1978, or 1974, in Bristol, England—no, Yate. The son of a butcher and a housewife, or a delivery driver and a hospital worker, he’s fat, he’s skinny, he’s an introverted workhorse, he’s a breeze-shooting exhibitionist given to drinking pint after pint of stout. For a while now, Banksy has lived in London: if not in Shoreditch, then in Hoxton. Joel Unangst, who had the nearly unprecedented experience of meeting Banksy last year, in Los Angeles, when the artist rented a warehouse from him for an exhibition, can confirm that Banksy often dresses in a T-shirt, shorts, and sneakers. When Unangst is asked what adorns the T-shirts, he will allow, before fretting that he has revealed too much already, that they are covered with smudges of white paint.

The creative fields have long had their shadowy practitioners, figures whose identities, whether because of scandalous content (the author of Story of O), fear of ostracism (Joe Klein), aversion to nepotism (Stephen King’s son Joe Hill), or conceptual necessity (Sacha Baron Cohen), remain, at least for a time, unknown. Anonymity enables its adopter to seek fame while shielding him from the meaner consequences of fame-seeking. In exchange for ceding credit, he is freed from the obligations of authorship. Banksy, for instance, does not attend his own openings. He may miss out on the accolades, but he’ll never spend a Thursday evening, from six to eight, picking at cubes of cheese.

Banksy is a household name in England—the Evening Standard has mentioned him thirty-eight times in the past six months—but his identity is a subject of febrile speculation. This much is certain: around 1993, his graffiti began appearing on trains and walls around Bristol; by 2001, his blocky spray-painted signature had cropped up all over the United Kingdom, eliciting both civic hand-wringing and comparisons to Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. Vienna, San Francisco, Barcelona, and Paris followed, along with forays into pranksterism and more traditional painting, but Banksy has never shed the graffitist’s habit of operating under a handle. His anonymity is said to be born of a desire—understandable enough for a ‘quality vandal,’ as he likes to be called—to elude the police. For years now, he has refused to do face-to-face interviews.”

••••••••••

Banksy’s very dark Simpsons couch gag:

Another Banksy post:

- Check out Exit Through the Gift Shop.