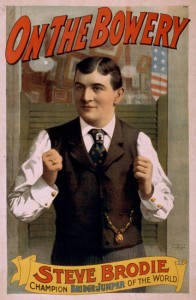

"Steve Brodie: Champion Bridge Jumper Of The World."

Steve Brodie was a New York bookie who gambled on the public’s need for heroes. Brodie grew famous in the late 19th century for an array of daring deeds, but he really only had one mighty talent: hoopla.

The popular Bowery character became a national celebrity in 1886 when he supposedly survived a leap from the recently opened Brooklyn Bridge–or so he claimed. Brodie likely had a dummy thrown off the span while he stayed out of harm’s way under a pier, but the press and public swallowed the story whole. Soon, the phrase “pulling a Brodie” was used whenever anyone performed a large, flamboyant gesture. He was the Houdini of hooey and the “daredevil” rode the publicity to success as a Manhattan saloon owner.

Once he tasted fame, Brodie wasn’t going away without a fight. The barkeep subsequently claimed a laundry list of other bridge dives and awesone feats that were likely equally bogus. But even if his boasts were illegitimate, Brodie’s notoriety landed him roles in legitimate theater, including 1894’s On the Bowery. The problem was, his whole life was a stage act and you never knew what was real and what was fake. As a result, Brodie’s obituary was written prematurely many times over the years.

The real one ran in The New York Times on February 1, 1901, under the title “Steve Brodie Dead; Picturesque Career of Famous Bowery Character Ends at San Antonio, Texas.” (The Times had previously pronounced him dead three years earlier.)

Another time Brodie was hastily drowned in a pool of ink was in a September 7, 1889 article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which reported that Brodie had been seriously, perhaps fatally, wounded (false) after becoming the second man to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel (false), just days after a barrel maker named Carlisle D. Graham had become the first to accomplish the feat (also false). An excerpt:

“The peculiar form of insanity which Steve Brodie has shown has comprised an ambition on his part to outdo anyone else in jumping from great heights, or in the undertaking of great risks. He has jumped from the Brooklyn Bridge, the Harlem High Bridge, the Cincinnati Suspension Bridge, over the Falls of the Genesee and from other great heights.

Annie Taylor, the first person to genuinely go over Niagara Falls in a barrel and survive. She performed the feat in 1901.

To-day it was reported he went over the Horseshoe Falls at Niagara, in a barrel, and that he has been taken up severely, and it is believed fatally, hurt. This last effort was doubtless made in emulation of the report that the idiot cooper named Graham went over the Falls in a barrel the other day. It is reputably declared that Graham did nothing of the kind, and that the report was a fraud to enable him to exhibit himself at paying rates in cheap museums.

There seems to be no doubt, however, that Brodie believed the Graham story and resolved to equal or exceed the attempt. If his temerity costs him his life, he will only have himself to blame. There will, however, be some sympathy with him because he was local to these communities and because he had undoubted pluck or recklessness. Should he emerge a cripple for life or should he finally recover, ground for his apprehension as a lunatic would be supplied by his last effort. It is a fact, however, that those who surround him are interested in urging him on to risk after risk, and that they make capital out of his peculiar form of audacious insanity. It will be remembered that Brodie’s most successful rival, Donelly, we think his name was, lately lost his life bridge jumping in England.

Legislation is required to deal with cranks of this kind. The community would not be critical of the character of such legislation, if only it was effective. Peremptorily to rate the cranks as insane, to shave their heads and to lock them up to be looked at by the public would stop their business.”