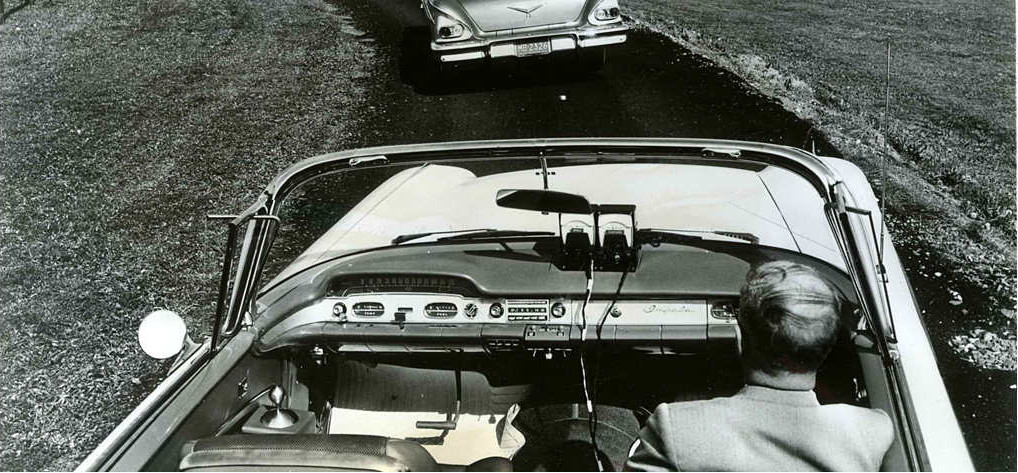

Many within the driverless sector think the technology is only five years from remaking our roads and economies. Perhaps they know enough to be sure of such a bold ETA, or perhaps they’re parked in an echo chamber. Either way, it appears this new tool will enter our lives sooner than later.

Beyond perfecting technology that works in all traffic situations and weather conditions are knotty questions about ethics, legislation, Labor, etc. Excerpts follow from two articles on the topic.

From Anjana Ahuja’s smart FT piece on the problem of crowdsourcing driverless ethics:

Anyone with a computer and a coffee break can contribute to MIT’s mass experiment, which imagines the brakes failing on a fully autonomous vehicle. The vehicle is packed with passengers, and heading towards pedestrians. The experiment depicts 13 variations of the “trolley problem” — a classic dilemma in ethics that involves deciding who will die under the wheels of a runaway tram.

In MIT’s reformulation, the runaway is a self-driving car that can keep to its path or swerve; both mean death and destruction. The choice can be between passengers and pedestrians, or two sets of pedestrians. Calculating who should perish involves pitting more lives against fewer, young against old, professionals against the homeless, pregnant women against athletes, humans against pets.

At heart, the trolley problem is about deciding who lives, who dies — the kind of judgment that truly autonomous vehicles may eventually make. My “preferences” are revealed afterwards: I mostly save children and sacrifice pets. Pedestrians who are not jaywalking are spared and passengers expended. It is obvious: by choosing to climb into a driverless car, they should shoulder the burden of risk. As for my aversion to swerving, should caution not dictate that driverless cars are generally programmed to follow the road?

It is illuminating — until you see how your preferences stack up against everyone else.•

From Keith Naughton’s Businessweek article on legislating the end of human drivers:

This week, technology industry veterans proposed a ban on human drivers on a 150-mile (241-kilometer) stretch of Interstate 5 from Seattle to Vancouver. Within five years, human driving could be outlawed in congested city centers like London, on college campuses and at airports, said Kristin Schondorf, executive director of automotive transportation at consultant EY.

The first driver-free zones will be well-defined and digitally mapped, giving autonomous cars long-range vision and a 360-degree view of their surroundings, Schondorf said. The I-5 proposal would start with self-driving vehicles using car-pool lanes and expand over a decade to robot rides taking over the road during peak driving times.

“In city centers, you don’t even want non-automated vehicles; they would just ruin the whole point of why you have a smart city,” said Schondorf, a former engineer at Ford Motor Co. and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV. “It makes it a dumb city.”

John Krafcik, head of Google’s self-driving car project, said in an August interview with Bloomberg Businessweek that the tech giant is developing cars without steering wheels and gas or brake pedals because “we need to take the human out of the loop.” Ford Chief Executive Officer Mark Fields echoed that sentiment last month when he said the 113-year-old automaker would begin selling robot taxis with no steering wheel or pedals in 2021.•