Long before everyone was a brand, James Michener was one. His name connected to a huge pile of words on pretty much any topic guaranteed a large advance and sales. He was far from a graceful writer, though that never impeded his success, which was propelled by an indefatigable zest for research. With his production methods and prolificity, he was almost a one-man corporation.

In 1983, as he did fieldwork for his proposed novel about Texas (which ended up, in Michener-esque fashion, being titled Texas), Andrea Chambers of People penned a profile of the septuagenarian scribe. The opening:

A sultry heat shrouded the groves of live oaks and the goat pastures on the edge of the Texas hill country as a state trooper drove down Interstate 35 from Austin to San Antonio. “This is the most dangerous highway in America,” he told his passenger, James Michener. “Going south is dangerous because there are stolen cars on the road to Mexico; heading north is even more dangerous because of the cocaine and marijuana smugglers coming up from Mexico.” Michener made a mental note of this statement, just as he had carefully considered the story, told him by a Texas banker, about a man who had deposited $1.25 million in his checking account. It seems that the man’s wife was going to New York City to shop, and he wanted her to be able to write all the checks she wanted. “This state has possibilities,” concluded the author. “How can I lose?”

How indeed. The 31 books of James Albert Michener have been translated into more than 50 languages, nine movies, four television shows and one musical, South Pacific. His novels, such as Chesapeake, Centennial and The Covenant, generally hit the top of best-seller lists within a week or so of their official publication date. Michener’s latest, Space, has held the No. 1 spot for six months and is tentatively scheduled to appear as a 10-part CBS miniseries next year. By that time Michener fans will have been presented with his opus on Poland, a multi-generational historical novel he finished researching and writing nearly a year ago.

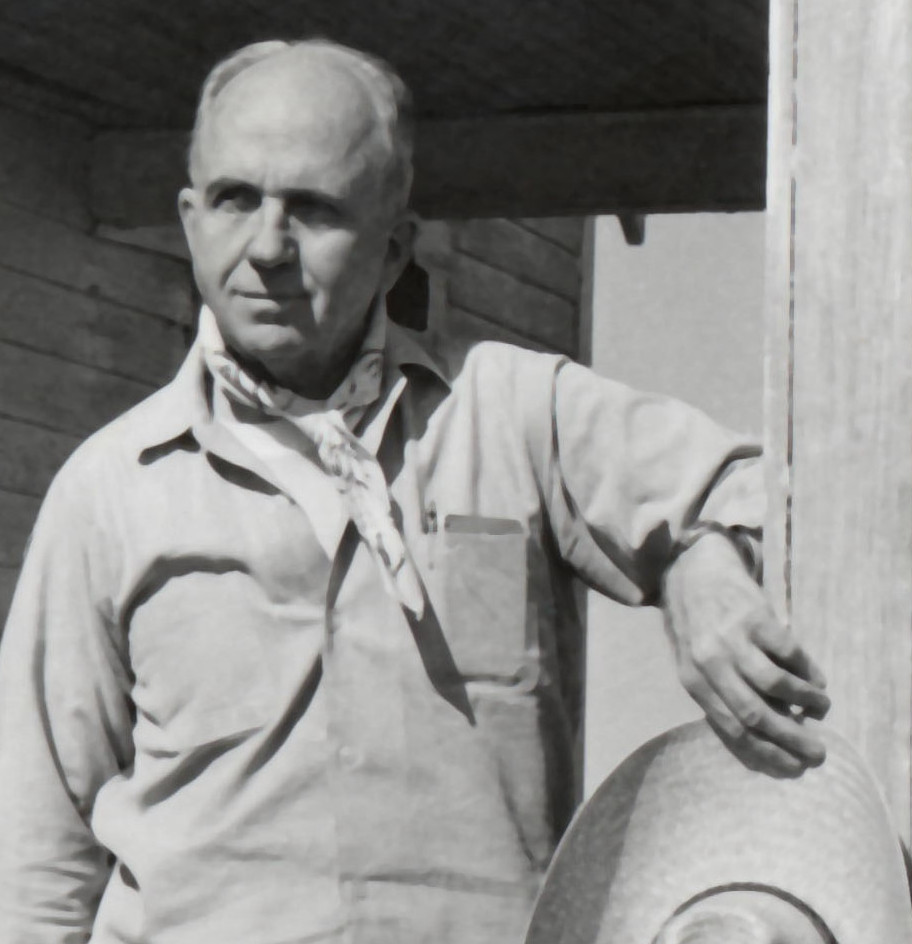

And then there is Texas, where the Wild West still lives and money spills off in rolls, like paper towels. Michener is now one and a half years deep into researching his saga of the state, beginning in 1527, when the Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca set off to explore the New World, and ending in 1984. “Have you ever met anyone who was inordinately, spiritually proud of being from New Hampshire?” he asks. “Here people love this state. They have a passion for Texas.” So has the Pennsylvania-raised Michener. Sporting a string tie and Stetson, he crisscrosses Texas, using as a base a rented Austin ranch house he shares with his wife, Mari. “I went to a dance hall outside Kerrville where there were 2,000 cowboys and their ladies,” the author recalls. “I saw fellas dancing with their hats on and gals in gingham. There it was, a little world nobody in Pittsburgh would ever have imagined. I was there very happily. I fit in rather easily.”

He felt right at home, too, spending four days on duty with a Texas Ranger in Big Bend country and following every foot of the Natchez Trace to trek the course of the early emigrants toward Texas. Quail hunting on the 823,000-acre King Ranch was especially appealing. “Seeing the shooting skill of those society women—boom, boom—was very sobering,” he says. “There is an illusion of a man’s world here. It may be a myth.” Another dubious myth is the shallow kingdom of lust and lucre displayed on the evening TV soaps. “I have to be very careful not to write a Yale University version of Dallas. I have to avoid the stereotypes.” He is also largely avoiding some of Texas’ great families—the Kings, the Hunts and, especially, the Johnsons. “I am not capable of dealing with Lyndon,” he says. “You would have to give him a disproportionate amount of space to do him even unequal justice. Besides, I am not obligated to cover everything.” What he will cover is the story of ranchers, cotton planters, oilmen and land developers, as well as the fate of the English, Spanish, Mexican, Scotch-Irish, German and other groups who settled in the state. Great historical figures, such as the Mexican general Santa Anna, Sam Houston and Cabeza de Vaca, will weave in and out of the plot.

To research the scene, Michener spends long hours reading at home or at his office at the Barker Texas History Center at the University of Texas in Austin, where he is a visiting scholar (he has devoured 400 books so far). “You can’t go out and just whomp it up. You have to be prepared,” he says. On his field trips, Michener may fill his senses with the smell of Texas winter wheat or the sight of grazing long-horns. He also seeks out local folk who can tell him what their jobs are like. “You don’t choose a dodo,” he explains. “If you’re going to pick a Mexican sheepherder, pick a good one.”

At 7:30 one morning just before his 76th birthday, Michener is off on yet another trip through the state. At the wheel of the car is his trusted “project editor,” John Kings, 59, a former editor of Reader’s Digest. An Englishman, Kings served as Michener’s field adviser and all-around organizer on Centennial and is doing the same for the Texas book. Mari Michener, 62, and Lisa Kaufman, 26, the novelist’s administrative assistant, are also along for the journey from Austin to San Antonio and exotic points west.

First stop is Fredericksburg (pop. 6,412) for coffee at a small café decorated with red-checkered tablecloths and a giant painted Comanche. Michener, a foundling whose early childhood was impoverished, relishes simple eateries as much as he likes a good cheap hotel and down-to-earth, salty conversation. “Aren’t you James Michener? I enjoyed your deal on Spain,” says a husky man in a hunter’s hat, referring to Michener’s 1968 non-fiction work Iberia. Jim, as his friends call him, quickly pulls up a chair and joins the man and his pals for coffee and doughnuts. Within a few minutes he has learned all about their jobs as well as a few tidbits about business practices in the area. There is something about Michener’s avuncular style that encourages people to tell him everything about themselves. The novelist absorbs it all, occasionally jotting down a number or date. For the most part, he relies on his memory to store the facts and feelings he will later pour into the novel.

His impressions of the café crowd duly recorded, Michener moves on to Comfort (pop. 1,460), home of the state’s only armadillo farm. “It’s bloody amazing,” he says. “It’s as if you had a skunk farm.” These slow-witted, shell-encased “Hoover hogs” (they were eaten like pork during the Depression) are run over on the roads by Texans, but are valuable for medical research. But to Michener, “The fact that they are so visibly ancient and that they have migrated north from Mexico becomes related to everything I’m writing about.” Promising that an armadillo will figure prominently in his novel, he strides forth to the wire coop where 26 of them are burrowing under hay. “Hello, little fella,” he clucks delightedly and swoops one up. His wife lets out a squeal of protest. “Oh, Cookie,” he says (the Micheners call each other “Cookie”), “they don’t scratch badly. I have handled wild hyenas, so I can handle this.”

Unscathed and overeducated with facts about the armadillo’s eating, reproductive and sleeping habits (they devour June bugs and dog food, breed four identical offspring from one egg, and emerge primarily at night), Michener is off again. After a stop at a restaurant for liver and onions (“I keep hoping I’ll find an edible chicken-fried steak,” he says of one prized Texas delicacy) and a visit to a Union war memorial in Comfort, he arrives at the ranch of Bob Ramsey and his wife, Willie. Michener, who likes to visit places two and three times, has already gone deer hunting near the Ramsey spread. Family and friends have gathered to welcome him back and proffer books to be signed. Michener inscribes them all. (“I only put my initials in paperbacks,” he jokes.) He is given a jar of venison jerky, a piece of hill country flint, Mrs. Ramsey’s etching, on a limestone slab, of a turkey, quail and armadillo, and a leather hatband adorned with arrowheads for his Stetson.

Visibly pleased, Michener pushes on to the nearby Frio River, a shallow waterway with such a smooth riverbed that a car can be driven down its center. Jim, naturally, tries it out, riding in the back of Bob Ramsey’s pickup. He then resumes his trip, gazing out at the cattle pastures and the windmills turning lazily against the darkening sky. “I love the expansiveness of this world,” he says. “I can hardly wait to get up in the morning and see it all. I’ve never been bored.”

In the course of his two-day trip, Michener will pace the boundaries of the Alamo so that he can better understand the battle, visit the Spanish Governor’s Palace and stroll the grounds of San Antonio’s San Juan Capistrano mission, which dates from 1731. He will also knock off some spicy Mexican meals, over which he discourses eloquently—for example, on the country with the most beautiful women (Burma) and on his literary influences (Milton, Dickens, Keats, the Bible, Wordsworth). He can describe in detail the floor plan of the Louvre or the Prado and can sing many of the world’s great operatic arias. Proud of his erudition, the Swarthmore-educated Michener quips that his epitaph will read: “Here lies James A. Michener, a man who never showed home movies or drank vin rosé.”

Back in his Austin study, he entertains himself with tapes of Bach or his new discovery, Willie Nelson, and sips pineapple juice. Then he diligently resumes work on his book, typing with two fingers. “I have never been big on the agony of writing,” he says. “I see no evidence that Tolstoy suffered from writer’s block.” Still, he frets that this novel will be his last. “I often think: ‘How will I hold all this together?’ ”

Most likely he will, and then go on to another epic.•