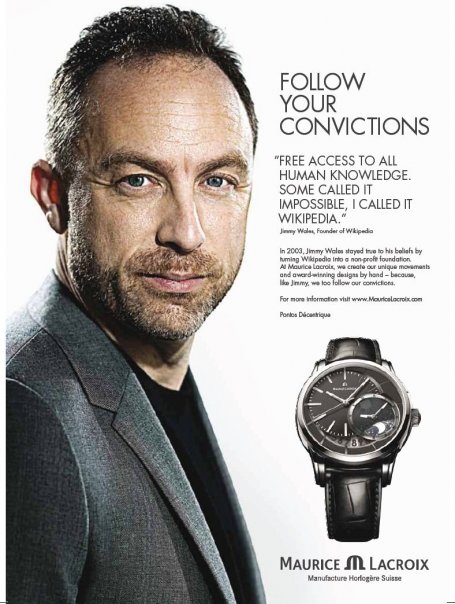

“Jimmy Wales Is Not an Internet Billionaire” is the title of Amy Chozick’s short, sharp New York Times Magazine portrait of the Wikipedia founder, a singular figure in the Information Age, who was right about crowdsourcing knowledge when almost everyone else thought he was wrong, when he was treated like a punchline. The collective nature of the virtual encyclopedia made it impossible for Wales to cash in, but somehow I think he’ll slide by. Let’s weep for others. An excerpt:

“Wikipedia, which is now available in 285 languages, gets more than 20 billion page views and roughly 516 million unique visitors a month. It is the fifth-most-visited Web site in the world behind Google, Yahoo, Microsoft and Facebook; and ahead of Amazon, Apple and eBay. Were Wikipedia to accept banner and video ads, it could, by most estimates, be worth as much as $5 billion. But that kind of commercial sellout would probably cause the members of the community, who are not paid for their contributions, to revolt. ‘The paradox,’ says Michael J. Wolf, managing director at Activate, a technology-consulting firm in New York and a member of the Yahoo! board, ‘is that what makes Wikipedia so valuable for users is what gets in its way of becoming a valuable, for-profit enterprise.’

Wales suffers from the same paradox. Being the most famous traveling spokesman for Internet freedom brings in a decent living, but it’s not Silicon Valley money. It’s barely London money. Wales’s total net worth, by most estimates, is just above $1 million, including stock from his for-profit company Wikia, a wiki-hosting service. His income is a topic of constant fascination. Type ‘Jimmy Wales‘ into Google and ‘net worth’ is the first pre-emptive search to pop up. ‘Everyone makes fun of Jimmy for leaving the money on the table,’ says Sue Gardner, the executive director of the Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit that runs Wikipedia.

Wales is well rehearsed in brushing off questions about his income. In 2005, Florida Trend magazine reported that he made enough money in his brief stint as an options-and-futures trader in Chicago, before starting Wikipedia, that he would never have to work again. But that was before he had to pay child support and rent for homes in Florida and London. When I brought up the topic recently, Wales seemed irritated. ‘It rarely crosses my mind,’ he said. ‘Reporters ask me all the time and expect me to say: ‘I’m heartbroken. Where’s my billion dollars?’ On two occasions, he compared himself to an Ohio car salesman. ‘There are car dealers in Ohio who have far more money than I’ll ever have, and their jobs are much, much less interesting than mine,’ he said during one conversation. When his net worth came up again, he brought up Ayn Rand. ‘Can you imagine Howard Roark saying, ‘I just want to make as much money as possible?’ Wales asked rhetorically.

Wales likes to invoke the higher purpose of Wikipedia.“

•••••

Encyclopedia Britannica infomercial, 1992: