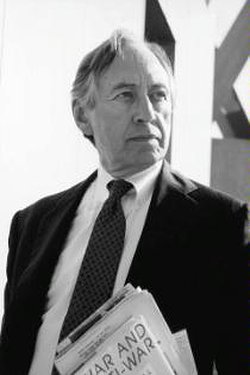

Alvin Toffler, the sociological salesman who anticipated and feared tomorrow, just died at 87.

Has there ever been a biography written about the man whose pants were forever being scared off? I’d love to know what it was about his life that positioned him, beginning in the 1960s, to look ahead at our future and be shocked. There was always a strong sci-fi strain to his work, though it’s undeniably important to think about how science and technology could go horribly wrong. By imagining the worst, perhaps we can avoid it. Like anyone else who toiled in speculative markets, Toffler was sometimes way off the mark, though he was also incredibly prescient on other occasions.

Below is an excerpt from his BBC obituary and a few Afflictor posts about Toffler from over the years.

From the BBC:

Online chat rooms

Although many writers in the 1960s focused on social upheavals related to technological advancement, Toffler wrote in a page-turning style that made difficult concepts easy to understand.

Future Shock (1970) argued that economists who believed the rise in prosperity of the 1960s was just a trend were wrong – and that it would continue indefinitely.

The Third Wave, in 1980, was a hugely influential work that forecast the spread of emails, interactive media, online chat rooms and other digital advancements.

But among the pluses, he also foresaw increased social alienation, rising drug use and the decline of the nuclear family.

Space colonies

Not all of his futurist predictions have come to pass. He thought humanity’s frontier spirit would lead to the creation of “artificial cities beneath the waves” as well as colonies in space.

One of his most famous assertions was: “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn and relearn.”•

“Who Is To Write The Evolutionary Code Of Tomorrow?”

A passage about genetic engineering, a fraught field but one with tremendous promise, from a 1978 Omni interview with Toffler conducted by leathery beaver merchant Bob Guccione:

Omni:

What’s good about genetic engineering?

Alvin Toffler:

Genetic manipulation can yield cheap insulin. It can probably help us solve the cancer riddle. But, more important, over the very long run it could help us crack the world food problem.

You could radically reduce reliance on artificial fertilizers–which means saving energy and helping the poor nations substantially. You could produce new, fast-growing species. You could create species adapted to lands that are now marginal, infertile, arid, or saline. And if you really let your long-range imagination roam, you can foresee a possible convergence of genetic manipulation, weather modification, and computerized agriculture–all coming together with a wholly new energy system. Such developments would simply remake agriculture as we’ve known it for 10,000 years.

Omni:

What is the downside?

Alvin Toffler:

Horrendous. Almost beyond our imagination, When you cut up genes and splice them together in new ways, you risk the accidental escape from the laboratory of new life forms and the swift spread of new diseases for which the human race no defenses.

As is the case with nuclear energy we have safety guidelines. But no system, in my view, can ever be totally fail-safe. All our safety calculations are based on certain assumptions. The assumptions are reasonable, even conservative. But none of the calculations tell what happens if one of the assumptions turns out to be wrong. Or what to do if a terrorist manages to get a hold of the crucial test tube.

A lot of good people are working to tighten controls in this field. NATO recently issued a report summarizing the steps taken by dozens of countries from the U.S.S.R. to Britain and the U.S. But what do we do about irresponsible corporations or nations who just want to crash ahead? And completely honest, socially responsible geneticists are found on both sides of an emotional debate as to how–or even whether–to proceed.

Farther down the road, you also get into very deep political, philosophical, and ecological issues. Who is to write the evolutionary code of tomorrow? Which species shall live and which shall die out? Environmentalists today worry about vanishing species and the effect of eliminating the leopard or the snail darter from the planet. These are real worries, because every species has a role to play in the overall ecology. But we have not yet begun to think about the possible emergence of new, predesigned species to take their place.•

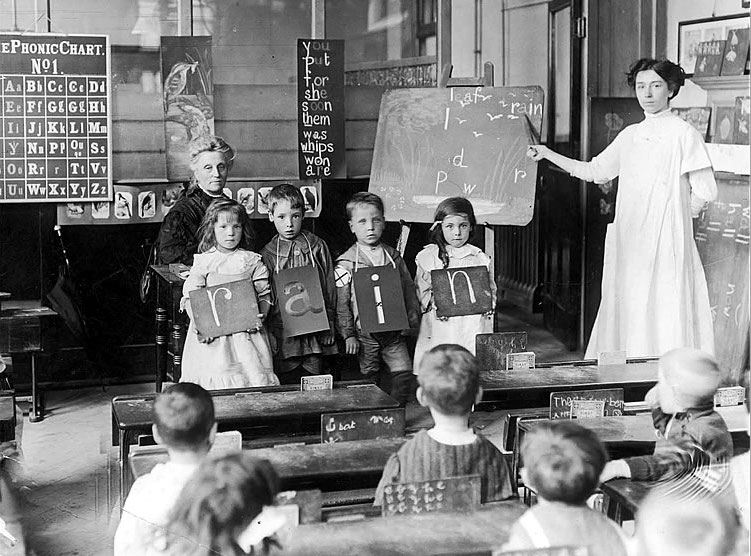

“Shut Down The Public Education System”

Toffler called for the dismantling of the U.S. public-education system in a 2007 interview at Edutopia. An excerpt:

Edutopia:

You’ve been writing about our educational system for decades. What’s the most pressing need in public education right now?

Alvin Toffler:

Shut down the public education system.

Edutopia:

That’s pretty radical.

Alvin Toffler:

I’m roughly quoting Microsoft chairman Bill Gates, who said, “We don’t need to reform the system; we need to replace the system.”

Edutopia:

Why not just readjust what we have in place now? Do we really need to start from the ground up?

Alvin Toffler:

We should be thinking from the ground up. That’s different from changing everything. However, we first have to understand how we got the education system that we now have. Teachers are wonderful, and there are hundreds of thousands of them who are creative and terrific, but they are operating in a system that is completely out of time. It is a system designed to produce industrial workers….

The public school system is designed to produce a workforce for an economy that will not be there. And therefore, with all the best intentions in the world, we’re stealing the kids’ future.

Do I have all the answers for how to replace it? No. But it seems to me that before we can get serious about creating an appropriate education system for the world that’s coming and that these kids will have to operate within, we have to ask some really fundamental questions.

And some of these questions are scary. For example: Should education be compulsory? And, if so, for who? Why does everybody have to start at age five? Maybe some kids should start at age eight and work fast. Or vice versa. Why is everything massified in the system, rather than individualized in the system? New technologies make possible customization in a way that the old system — everybody reading the same textbook at the same time — did not offer.•

“This Technology Is Exacting A Heavy Price”

Orson Welles narrates this 1972 documentary that McGraw-Hill produced about sociologist Toffler‘s gargantuan 1970 bestseller, Future Shock. Toffler caused a sensation with his views about the human incapacity to adapt in the short term to remarkable change, in this case of the technological variety. The movie is odd and paranoid and overheated and fun.