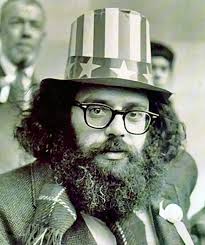

Allen Ginsberg was a great poet and performer, if a dubious person in other ways. Here he is in 1965 giving one of his rapturous readings at the Royal Albert Hall.

You are currently browsing articles tagged Allen Ginsberg.

Tags: Allen Ginsberg

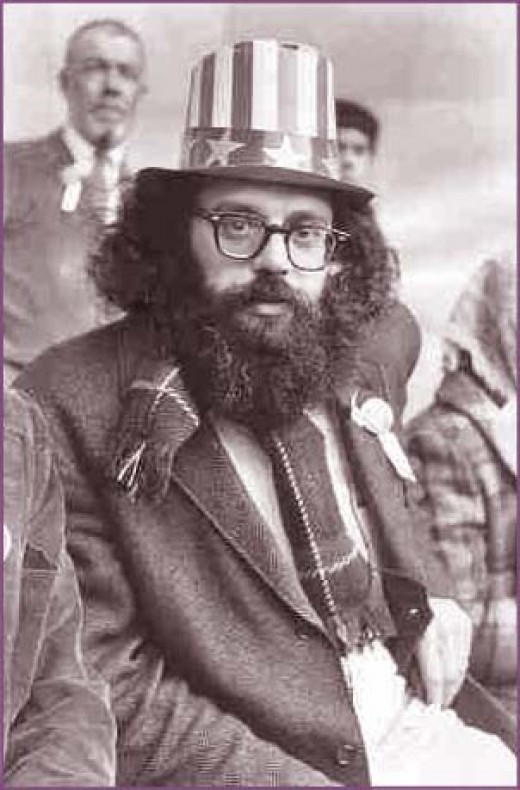

Allen Ginsberg in London in 1967, talking about how communication via technology changes the meaning, alters the context. And as the screens have gotten smaller and more ubiquitous, we’re not just lost in our own surroundings but in our own heads as well.

Tags: Allen Ginsberg

I suppose the best argument for a war on drugs is that using narcotics is thought to lower IQ and if enough people in a society make themselves less intelligent, it puts that society at a disadvantage in the global marketplace. But here’s the problem with the prohibition of drugs: It doesn’t work. Not at all. Criminalizing something that consenting adults want to do just serves to enable a black market. And if people don’t have access to street drugs, they’ll abuse Oxycodone and the like. The war on drugs is not going to stop usage so we should stop the war on drugs. At Tom Dispatch, Lewis Lapham recalls his sole encounter with acid:

“So too in the 1960s, the prudent becoming of an American involved perilous transmigrations, psychic, spiritual, and political. By no means certain who I was at the age of 24, I was prepared to make adjustments, but my one experiment with psychedelics in 1959 was a rub that promptly gave me pause.

Employed at the time as a reporter at the San Francisco Examiner, I was assigned to go with the poet Allen Ginsberg to the Stanford Research Institute there to take a trip on LSD. Social scientists opening the doors of perception at the behest of Aldous Huxley wished to compare the flight patterns of a Bohemian artist and a bourgeois philistine, and they had asked the paper’s literary editor to furnish one of each. We were placed in adjacent soundproofed rooms, both of us under the observation of men in white coats equipped with clipboards, the idea being that we would relay messages from the higher consciousness to the air-traffic controllers on the ground.

Liftoff was a blue pill taken on an empty stomach at 9 a.m., the trajectory a bell curve plotted over a distance of seven hours. By way of traveling companions we had been encouraged to bring music, in those days on vinyl LPs, of whatever kind moved us while on earth to register emotions approaching the sublime.

Together with Johann Sebastian Bach and the Modern Jazz Quartet, I attained what I’d been informed would be cruising altitude at noon. I neglected to bring a willing suspension of disbelief, and because I stubbornly resisted the sales pitch for the drug — if you, O Wizard, can work wonders, prove to me the where and when and how and why — I encountered heavy turbulence. Images inchoate and nonsensical, my arms and legs seemingly elongated and embalmed in grease, the sense of utter isolation while being gnawed by rats.

To the men in white I had nothing to report, not one word on either the going up and out or the coming back and down. I never learned what Ginsberg had to say. Whatever it was, I wasn’t interested, and I left the building before he had returned from what by then I knew to be a dead-end sleep.”

Tags: Allen Ginsberg, Lewis Lapham

Allen Ginsberg shares an LSD-inspired poem with William F. Buckley in the first video. Buckley entertains a drunk Jack Kerouac in the second clip.

More William F. Buckley posts:

- Buckley meets Groucho Marx. (1967)

- Buckley interviews Muhammad Ali. (1968)

- Buckley debates James Baldwin. (1965)

"He was literally and figuratively behind the wheel of our bus, driving it the way Charlie Parker worked the saxophone." (Image by Joe Mabel.)

In a 1994 Paris Review Q&A, Ken Kesey explains how Beat muse Neal Cassady wound up driving Furthur, the Merry Pranksters’ bus:

“Cassady was around us often. There was one incident in particular when he truly impressed me not only as a madman, genius, and poet but also as an avatar—someone in contact with other powers. He took me to a racetrack near San Francisco. He was driving and talking very fast, checking his watch frantically, hoping we would get to the track on time. If we got to the track just before the last three races, we’d get in free. We made it just in time and we bet on the last two races. Cassady had a theory about betting he’d learned in jail from someone named Knee-Walking Jackson. His theory was that the third favorite at post time is often the horse most likely to upset the winner and make big money. Cassady’s strategy was to step up to the tellers at the ticket booths just at post time. He’d glance up to see who was third favorite and put money on that horse. He didn’t look at the horses, the jockeys, or the racing sheets. He said to me, This is going to be the one, I can feel it. He asked me for ten bucks and I gave it to him. He put three dollars down with my ten. Given the odds we would have made some good money. We went right down to the line to watch, and it was a close race, neck and neck. I’m no horse fan, but I was getting into it because it looked like the third favorite could win. There was a photo finish and Cassady suddenly tore up his tickets and left. I followed him back to the car and could hear the announcement: We have a photo finish and the winner is . . . It turned out to be the favorite. Neal was so confident of his vision that if he lost, he never waited around or looked back.

Cassady was a hustler, a wheeler-dealer, a conniver. He was a scuffler. He never had new clothes but was always clean, and so were his clothes. He always had a toothbrush and was always trying to sell us little things and trying to find a place where he could wash up. Cassady was an elder to me and the other Pranksters, and we knew it. He was literally and figuratively behind the wheel of our bus, driving it the way Charlie Parker worked the saxophone. When he was driving he was improvising an endless monologue about what he was seeing and thinking, what we were seeing and thinking, and what we had seen, thought, and remembered. Proust was his literary hero and he would quote long passages from Proust and Melville from memory, lacing his revelations with passages from the Bible. He was a great teacher and we all knew it and were affected by him.”

••••••••••

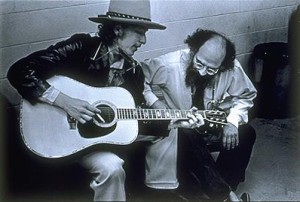

Cassady in conversation with Allen Ginsberg, 1965:

Tags: Allen Ginsberg, Ken Kesey, Neal Cassady

Great find by the Essayist, which uncovered an online version of “The Great Marijuana Hoax,” Allen Ginsberg’s 1966 Atlantic essay in defense of the illegal herb, which was then vilified to hysterical proportions. An excerpt:

“This essay, conceived by a mature middle-aged gentleman, the holder at present of a Guggenheim Fellowship for creative writing, a traveler on many continents with experience of customs and modes of different cultures, is dedicated to those who have not smoked marijuana, who don’t know exactly what it is but have been influenced by sloppy, or secondhand, or unscientific, or (as in the case of drug-control bureaucracies) definitely self-interested language used to describe the marijuana high pejoratively. I offer the pleasant suggestion that a negative approach to the whole issue (as presently obtains in what are aptly called square circles in the USA) is not necessarily the best, and that it is time to shift to a more positive attitude toward this specific experience. If one is not inclined to have the experience oneself, this is a free country and no one is obliged to have an experience merely because friends, family, or business acquaintances have had it and report themselves pleased. On the other hand, an equal respect and courtesy are required for the sensibilities of one’s familiars for whom the experience has not been closed off by the door of Choice.”

Tags: Allen Ginsberg