We should always err on the side of whistleblowers like Edward Snowden because they’ve traditionally served an important function in our democracy, but that doesn’t mean the former NSA employee has changed America for the better–or much at all.

In the wake of 9/11, most in the country wanted to feel safe and were A-OK with the government taking liberties (figuratively and literally). Big Brother became the favorite sibling. The White House position and policy has shifted somewhat since Snowden went rogue, but I believe from here on in we’re locked in a cat-and-mouse game among government, corporations and citizens, with surveillance and leaks a permanent part of the landscape. The technology we have–and the even more powerful tools we’ll have in the future–almost demands such an arrangement. We’re all increasingly inside a machine now, one that moves much faster than legislation. That’s the new abnormal.

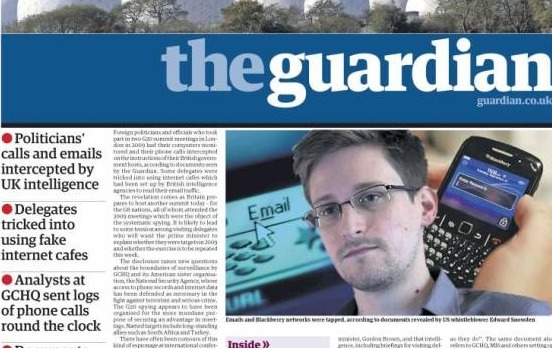

The Financial Times set up an interview with Snowden conducted by Alan Rusbridger, former EIC of the Guardian, the publication that broke the story. The subject is unsurprisingly much more hopeful about the impact of his actions than I am. An excerpt:

Alan Rusbridger:

It’s now, what, three years since the revelations?

Edward Snowden:

It’s been more than three years. June 2013.

Alan Rusbridger:

Tell me first how the world has changed since then. What’s changed as a result of what you did, from your perspective? Not from your personal life, but the story you revealed.

Edward Snowden:

The main thing is that our culture has changed, right? There are many different ways of approaching this. One is we look at the structural changes, we look at the policy changes, we look at the fact that the day the Guardian published the story, for example, the entire establishment leaped out of their chairs and basically said ‘This is untrue, it’s not right, there’s nothing to see here’. You know, ‘Nobody’s listening to your phone calls’, as the president said very early on. Do you remember? I think he sort of spoke with the voice of the establishment in all of these different countries here, saying, ‘I think we’ve drawn the right balance’.

Then you move on to later in the same year when the very first court verdicts began to come forward and they found that these programmes were ‘unlawful, likely unconstitutional’ — that’s a direct quote — and ‘Orwellian in their scope’ — again a quote. And this trend continued in many different courts. The government realising that these programmes could not be legally sustained and would have to be amended if they were to keep any of these powers at all. And to avoid a precedent that they would consider damaging, which is that the Supreme Court basically locks the power of mass surveillance away from them forever, they need a pretty substantial pivot, whereby January of 2014 the president of the US said that, well, of course you could never condone what I did. He believes that this has made us stronger as a nation and that he was going to be recommending changes to a law of Congress, which then later, again this is Congress, they don’t do anything quickly, they actually did amend the law.

Now, they would not likely have made these changes to law on their own without the involvement of the Courts. But these are all three branches of government in the US completely changing their position. In March of 2013, the Supreme Court flushed the case, right, saying that this is a state secret, we can’t talk about it and you can’t prove that you were spied on. Then suddenly when everyone can prove that they had been spied on, we see that the law changed. So that’s sort of the policy side of looking at that. And people can look at the substance there and say, ‘This is significant’. Even though it didn’t solve the problem, it’s a start and, more importantly, it empowers people, it empowers the public; it shows that, for the first time in four years, we can actually start to impose more oversight on intelligence agencies, on spies, rather than giving them a free pass to do whatever, simply because we’re scared, which is understandable but clearly not ethical.

As online threats race up national security agendas and governments look at ways of protecting their national infrastructures a cyber arms race is causing concern to the developed world. Then there’s the other way of looking at it, which is in terms of public awareness.•