We like to think we have empathy, but how can we truly see things through someone else’s eyes, especially if their reality has known extremes ours hasn’t? To help us, some of them paint a picture.

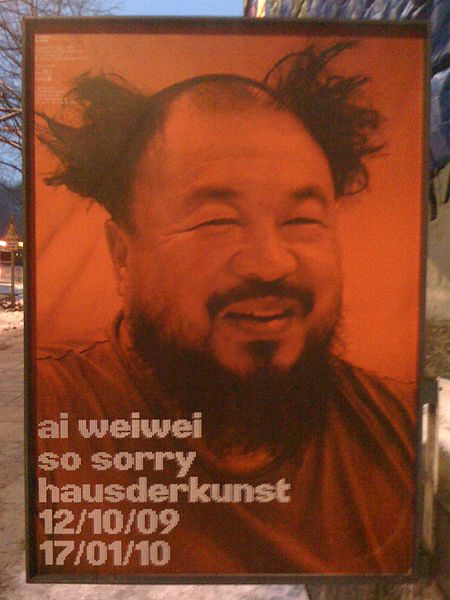

Ai Weiwei does that, in many different ways. The Chinese artist has been imprisoned and beaten and detained, continually detained. There seems to be some sort of detente in his current state of relations with government authorities, but his experiences don’t go away–they shape him. So he may view consumerism and technology differently than I do, but his feelings from within his context are just as valuable. Maybe more so.

For a NYRB article, Ian Johnson facilitated a pizzeria lunch in Berlin between Ai Weiwei, his passport in hand once again, and exiled writer Liao Yiwu. The artist believes China, viewed broadly, is better for its modernization, and that the world is mostly improved by social media. An excerpt:

Question:

What do you think of think of the modernization theory—that when people get to a certain standard of living, when people are no longer just concerned with food or shelter, they start to demand things. We could see that historically in South Korea, or Taiwan, say thirty years ago. Does that have any relevance to China today?

Ai Weiwei:

It does, very obviously. If you see those young kids, they’re better off than their parents. They’ve been sent to study abroad. They can travel more freely. They get on the internet. They get iPhones and iPads and video games.

Question:

Are the Chinese authorities aware of it?

Ai Weiwei:

They are aware of it, but I don’t know to what degree, and I don’t know if they have the right measures. To understand the crisis you need a philosophical mind and the system never really had that kind of discussion—like the one we’re having now, and to openly discuss it. To openly discuss it means first you have a balanced view and you get every mind involved, so the solution will be more democratic rather than some authoritarian solution, which will just create more problems. All they care about are results, but life is about more than results. It’s about our involvement, our passive involvement in each individual’s mind, and that’s why we can say we love it or we hate it.

Question:

One way people engage is through social media. Obviously that’s changed things a lot but it also seems to encourage a bit of a, not civil society, but uncivil society—people cursing each other and so on.

Ai Weiwei:

It does much more good than evil. Of course, if you have a society that never had a public platform or public property, it’s something new. It becomes an outlet for huge pressure. It’s like an explosion, but only because the building is not well-designed. If you had ten outlets [of expression], people would be much more friendly and courteous.

That’s why a modern structure is so important to deal with contemporary problems. It’s not about ideology. All those concepts of democracy or freedom of speech. It’s really about efficient tactics to solve modern problems. That problem is to recognize and protect each individual’s rights and to contribute them to society. Of course China is far from that. First it needs a philosophical understanding and then it needs laws to protect those rights and legislation designed for separate powers. All of that is not established in China now and that’s why I say China is not a modern society.•