For all the flak the government takes–even by plenty of those in the government–its record of research investment is pretty spectacular. We’re not talking about only the Internet but the transistor itself, among many other innovations. As the anti-government forces have chipped away at such state-sponsored R&D, larger tech companies are trying to birth their own Bell Labs. From Claire Cain Miller at the New York Times:

“Silicon Valley, where toddler-aged companies regularly sell for billions, may be the most vibrant sector of the U.S. economy, fueling a boom in markets from housing to high-end toast (how many $4-a-slice artisanal bread bars does a place really need?). But as recent innovations — apps that summon cabs, say, or algorithms that make people click on ads — have been less than world-changing, there is a fear that the idea machine is slowing down. And while Silicon Valley mythology may suggest that modern-day innovation happens in garages and college dorm rooms, its own foundations were laid, in large part, through government research. But during the recession, government funding began to dwindle. The federal government now spends $126 billion a year on R. and D., according to the National Science Foundation. (It’s pocket change compared with the $267 billion that the private sector spends.) Asian economies now account for 34 percent of global spending; America’s share is 30 percent.

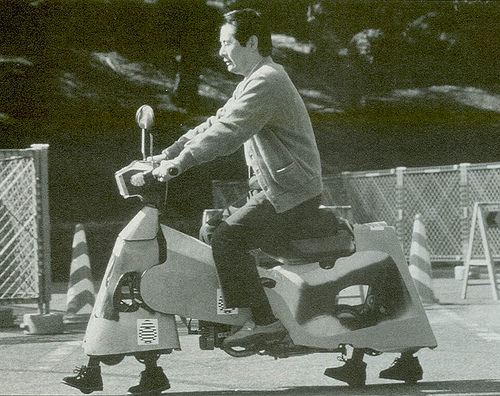

Perhaps more crucial, the invention of much of the stuff that really created jobs and energized the economy — the Internet, the mouse, smartphones, among countless other ideas — was institutionalized. Old-fashioned innovation factories, like Xerox PARC and Bell Labs, were financed by large companies and operated under the premise that scientists should be given large budgets, a supercomputer or two and plenty of time to make discoveries and work out the kinks of their quixotic creations. Back then, after all, Xerox and AT&T, their parent companies, made so much money that few shareholders cared about the cost. ‘It’s the unique ingredient of the U.S. business model — not just smart scientists in universities, but a critical mass of very smart scientists working in the neighborhood of commercial businesses,’ says Adrian Slywotzky, a partner at Oliver Wyman, the global management consulting firm. ‘Then that investment was cut way back.’ By the ’80s, AT&T was being taken apart by the government; Xerox PARC, like other labs, was diminished by impatient shareholders and, in some cases, the very technology it helped create.

Most of the insurgent tech companies, with their razor focus on advancing the Internet, were too preoccupied to set up their own innovation labs. They didn’t have much of an incentive either. Start-ups became so cheap to create — founders can just rent space in the cloud from Amazon instead of buying servers and buildings to house them — that it became easier and more efficient for big companies to simply buy new ideas rather than coming up with the framework for inventing them. Some of Google’s largest businesses, like Android and Maps, were acquired. ‘M. and A. is the new R. and D.’ became a popular catchphrase.

But in the past few years, the thinking has changed, and tech companies have begun looking to the past for answers. In 2010, Google opened Google X, where it is building driverless cars, Internet-connected glasses, balloons that deliver the Internet and other things straight out of science fiction.”