What’s easier, de-extincting an average example of a bygone species or engineering a superior version of one still in existence?

The counterintuitive answer is that they may be equally difficult even though it might be assumed the latter would be relatively simpler. Creating a Mammoth from scratch could be no harder than “building” another Secretariat. Those new mammoths, however, won’t be exactly the same as their “ancestors” nor would a new champion be exactly like the Triple Crown winner of yore. There are just too many variables. But exactitude isn’t as important as progress. These creatures will be new and different, and the same will be said eventually of enhanced humans. That’s where we’re headed. It’s a brave new world, and a fraught one, but we probably won’t survive without such experimentation.

Excerpts follows from two new articles: “The Mammoth Cometh,” Nathaniel Rich’s excellent New York Times Magazine piece which will surely have a place on my “Great 2014 Nonfiction Pieces Online For Free” list if I’m still doing this blog by the end of the year; and “Can Science Breed the Next Secretariat?” Adam Piore and Katie Bo Williams’ Nautilus article about recreating an incredibly rare natural mutation.

___________________________

From “The Mammoth Cometh”:

There is no authoritative definition of “species.” The most widely accepted definition describes a group of organisms that can procreate with one another and produce fertile offspring, but there are many exceptions. De-extinction operates under a different definition altogether. Revive & Restore hopes to create a bird that interacts with its ecosystem as the passenger pigeon did. If the new bird fills the same ecological niche, it will be successful; if not, back to the petri dish. ‘It’s ecological resurrection, not species resurrection,’ Shapiro says. A similar logic informs the restoration of Renaissance paintings. If you visit The Last Supper in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, you won’t see a single speck of paint from the brush of Leonardo da Vinci. You will see a mural with the same proportions and design as the original, and you may feel the same sense of awe as the refectory’s parishioners felt in 1498, but the original artwork disappeared centuries ago. Philosophers call this Theseus’ Paradox, a reference to the ship that Theseus sailed back to Athens from Crete after he had slain the Minotaur. The ship, Plutarch writes, was preserved by the Athenians, who “took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their place.” Theseus’ ship, therefore, “became a standing example among the philosophers . . . one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same.”

What does it matter whether Passenger Pigeon 2.0 is a real passenger pigeon or a persuasive impostor? If the new, synthetically created bird enriches the ecology of the forests it populates, few people, including conservationists, will object. The genetically adjusted birds would hardly be the first aspect of the deciduous forest ecosystem to bear man’s influence; invasive species, disease, deforestation and a toxic atmosphere have engineered forests that would be unrecognizable to the continent’s earliest European settlers. When human beings first arrived, the continent was populated by camels, eight-foot beavers and 550-pound ground sloths. “People grow up with this idea that the nature they see is ‘natural,’ ” Novak says, “but there’s been no real ‘natural’ element to the earth the entire time humans have been around.”

The earth is about to become a lot less “natural.” Biologists have already created new forms of bacteria in the lab, modified the genetic code of countless living species and cloned dogs, cats, wolves and water buffalo, but the engineering of novel vertebrates — of breathing, flying, defecating pigeons — will represent a milestone for synthetic biology. This is the fact that will overwhelm all arguments against de-extinction. Thanks, perhaps, to Jurassic Park, popular sentiment already is behind it. (“That movie has done a lot for de-extinction,” Stewart Brand told me in all earnestness.) In a 2010 poll by the Pew Research Center, half of the respondents agreed that “an extinct animal will be brought back.” Among Americans, belief in de-extinction trails belief in evolution by only 10 percentage points. “Our assumption from the beginning has been that this is coming anyway,” Brand said, “so what’s the most benign form it can take?”

What is coming will go well beyond the resurrection of extinct species. For millenniums, we have customized our environment, our vegetables and our animals, through breeding, fertilization and pollination. Synthetic biology offers far more sophisticated tools. The creation of novel organisms, like new animals, plants and bacteria, will transform human medicine, agriculture, energy production and much else.•

__________________________

From “Can Science Breed the Next Secretariat?”:

Any trainer with good horse sense could have told you that Trading Leather was something special before he raced from the pack, overtook Galileo Rock, and galloped to victory in the prestigious Irish Derby last June. All one needed to do was take in the magnificent crevasse of muscle running down the back of his hindquarters, the length and architecture of his limbs, his inimitable dignity of motion.

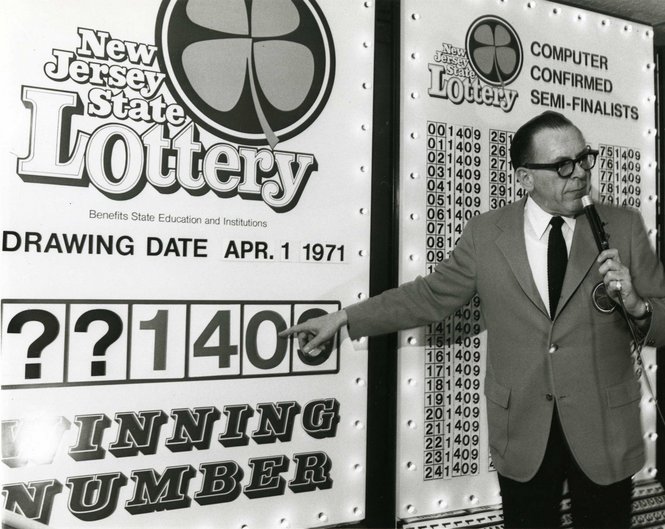

But the legendary trainer who bred him, Jim Bolger, 72, had an extra reason to believe his prized colt was suited for the mid-distance race on the storied track at County Kildare. Bolger had Trading Leather tested for the “speed gene.” He knew, like an expectant mother who has an embryo tested to find out the sex of her baby, what distance Trading Leather was optimally suited to run and at about what age he’d be ready to run it.

Genetics testing has arrived in the world of thoroughbred horse racing. Bolger, whose name is synonymous with success in the fickle game of horse racing, has called it “the most important thing that has happened to breeding since it began over 300 years ago.” The speed gene is now central to the decisions Bolger makes every year when he sits down to pencil out which of his roughly 100 thoroughbreds to mate, and when to begin training his most promising yearlings. Merging specific gene types from his sires and mares, he believes, can result in new lines of lucrative champions. He’s so sure of the science behind the speed gene that he opened a company to sell a speed gene test to his fellow breeders and trainers.

Genetic testing has long been a dream of the sports industry. Since the human genome was mapped in 2000, sports scientists have been racing to identify genes that contribute to athletic superiority. The first test purporting to evaluate human athletic potential hit the market in Australia back in 2004 (arriving in the United States in 2008), a year after a team of researchers published a study linking a single gene to a type of muscle fiber involved in producing the explosive, short-duration bursts of energy needed for sports like power lifting and sprints. This January, Uzbekistan became the first nation to announce a plan to use genetic tests to evaluate future Olympians. The tests of children as young as 10 will be overseen by a team of geneticists who have been studying the genes of the nation’s best athletes for two years, and are preparing a report detailing 50 genes that will form the basis of their talent search.

Every new announcement of a ‘sports gene’ seems to stir up a debate about science and culture, nature and nurture. Can genes account for athletic performance? Are they any match for expert training?•