The contemporary Western attitude toward architecture is to protect the jewels, preserve them. Not so in Japan, a nation of people Pico Iyer refers to in a striking T Magazine essay as “pragmatic romantics.” Iyer writes of ancient buildings being regularly replaced by replicas in the same manner that some citizens hire elderly actors to portray deceased grandparents at family functions. It’s just a different mindset. The opening:

EVERY 20 YEARS, the most sacred Shinto site in Japan — the Grand Shrine at Ise — is completely torn down and replaced with a replica, constructed to look as weathered and authentic as the original structure built by an emperor in the seventh century. To many of us in the West, this sounds as sacrilegious as rebuilding the Western Wall tomorrow or hiring a Roman laborer to repaint the Sistine Chapel once a generation. But Japan has a different sense of what’s genuine and what’s not — of the relation of old to new — than we do; if the historic could benefit from a little help from art, or humanity, the reasoning goes, then wouldn’t it be unnatural not to provide it?

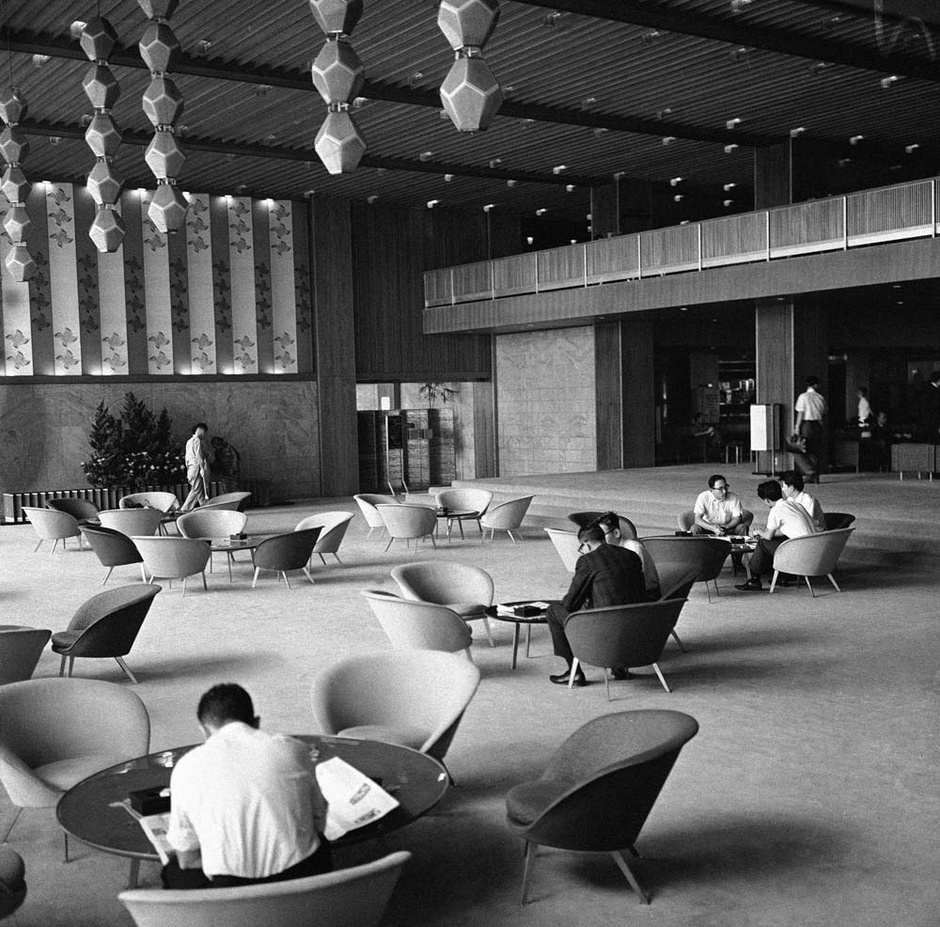

The motto guiding Japan’s way of being might be: New is the new old. For proof, you need only look at three recent high-profile and much-debated demolition jobs in Tokyo. The Hotel Okura, an icon of Japanese Modernism built in 1962 to commemorate the country’s arrival in the major leagues of nations as the host of the 1964 Olympics and cherished for its unique and atmospheric lobby, is currently being reduced to rubble in favor of two no doubt anonymous glass towers, meant to announce Japan’s continuing position in the big leagues, as the host of the 2020 Olympics. The once state-of-the-art National Olympic Stadium, designed by Mitsuo Katayama for the 1964 event, is being replaced by tomorrow’s idea of futurism: a new structure that was, until recently, set to be designed by Zaha Hadid. Even Tsukiji, the world’s largest fish market and the mainstay of jet-lagged sightseers for decades — is being mostly moved to a shopping mall, with the assurance that a copy of a place can sometimes look more authentic than the place itself. These erasures — most notably of the Okura, which became the personal cause of Tomas Maier, the creative director of Bottega Veneta — have elicited protests from devoted aesthetes the world over: What could the Japanese be thinking?

The answer is simple: The Japanese are different from you and me. They don’t confuse books with their covers.•