Jackie Collins was the ultimate Hollywood insider, yet she was, British-born, also a stranger, possessing a distance that served her well when writing of the morals (or lack thereof) of the glittering stars in that particularly bawdy time when the Sexual Revolution made Los Angeles even more louche. She wasn’t writing Nathanael West but instead focused south of the belt, and it served her well. From an appropriately very lively (and sadly unbylined) postmortem in the Economist:

There was probably no one in the room who knew Hollywood better. She was its resident anthropologist, anatomiser and guide. The Grill for lunch. Mr Chow’s or Cecconi’s for dinner. Soho House for the best view of the whole staggeringly beautiful city of Los Angeles. Neiman-Marcus in Beverly Hills for shoes and jewels.

But this was only the start. Jackie C. also knew the places of furtive whispers and hot sheets. All of them. She had experienced 90210’s wicked side ever since the age of 15, when she made Errol Flynn chase her round a table in the louche Chateau Marmont Hotel and fought off Sammy Davis Jr. Ever since she’d two-timed a couple of car mechanics on Sunset Boulevard. And ever since Marlon Brando, at a party, had admired her magnificent 39-inch breasts at the start of their brief but fabulous affair. Now for trysts she recommended the Bel-Air (“very discreet”) and Geoffrey’s at the Beach for waves, lights and general sexiness.

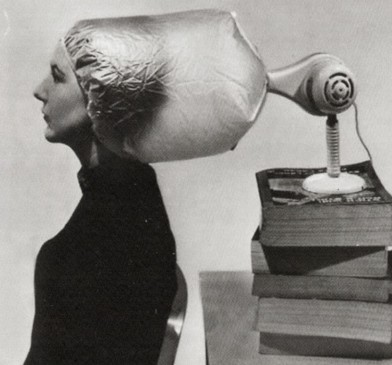

Yet this was still not why she was the most potent and dangerous person in the room. She was a writer. Over the years, quietly and intently, she had watched what the denizens of Hollywood were doing, and listened to what they were saying. Who had ditched whom. Who was eyeing up whom. Who had slept with whom, and full details. From her corner table at Spago’s, or half-hidden by a drape in a night-club, or under the dryer at Riley’s hair and nail salon, she would gather every last crumb of gossip and rush to the powder room to write it down. She turned it into sizzling novels in which, every six pages or so, enormous erections burst out of jeans, French lace panties were torn off and groans of delight rang through the palm-fringed Hollywood air. There were 32 books in all, with titles like The Stud, The Bitch, Lethal Seduction and Hollywood Divorces. She had sold half a billion of them worldwide. Anyone she met might turn up there. Stars would beg her not to put them in her stories, and she would tell them they were there, toned down, already. Hard luck.•