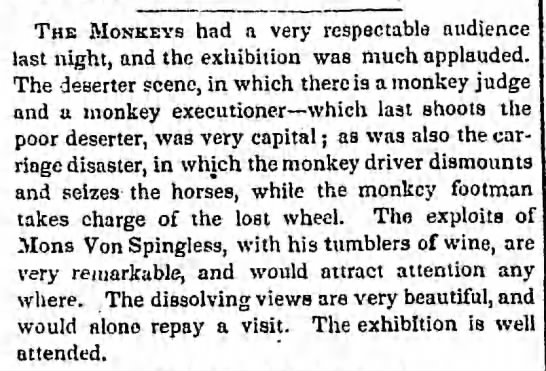

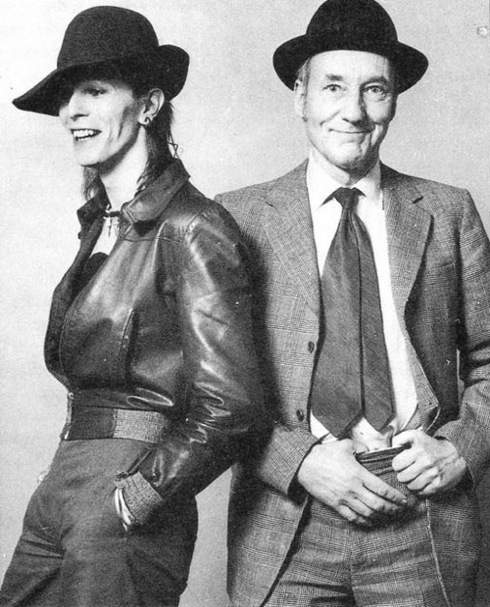

Talk-show host Stanley Siegel just died, and at one point that would have been huge news in New York City.

Before Howard Stern and Reality TV, venues that encourage emotionally damaged recruits to act out every last pathology to pump up the ratings, television host Siegel and his questionable taste and utter neuroses were considered controversial. During the 1970s, his raucous live morning show on the local ABC affiliate made his name as famous in New York as any politician, athlete or Broadway star.

Siegel invited his therapist to psychoanalyze him each week on the air, allowed a wasted Truman Capote to sit down as a guest when he was clearly in no condition to do so and angered a good number of politicos and entertainers with his brash, often-insulting questions. He was the anti-Carson, and it worked wonderfully well for a while.

In the 1977 New York magazine article, “Give Us a Kiss, Stanley,” which was written by journalist and playwright Jonathan Reynolds, Siegel was analyzed a little bit more, captured at the height of his entertaining narcissism. An excerpt:

Every day, Siegel wallows guiltlessly in his own persona, exulting in the dust, high jinx and cobwebs he reveals. He is funny, frightened, confused, weepy, sexual, evangelistic, and overbearing right in front of everybody’s eyes. In terms of emotional exhibitionism, Stanley Siegel makes Jack Paar look like Thomas Pynchon.

In the nearly two years he has been on WABC-TV at 9am, he has sextupled the ratings of his dreary predecessors, increased WABC’s rate card from $35 to $100 for every 30-second spot sold, knocked the venerable Not for Women Only and mega-venerable Concentration out of their time slots, and gained a host of admirers from Robert Evans to Eleanor Holmes Norton.

People tune in to the Stanley Siegel Show to see how Stanley feels–for if there is one predictable element in the program, it is that it will always be clear just how Stanley feels — for if there is one predictable element in the program, it is that it will always be clear just how Stanley feels. He has turned famous guests, WABC-TV’s employees and batches of stay-at-homes into an army of psychotherapists, and how can a psychotherapist not tune in to see how the patient is progressing–or deteriorating?•

________________________

Art Linkletter’s daughter Diane plunged to her death from a six-story window in 1969, perhaps influenced to suicide by LSD. Timothy Leary was, of course, the most famous proponent of the drug, so Siegel, that button-pusher, thought it a good idea in 1977 to have Linkletter and the guru speak by phone on live TV.

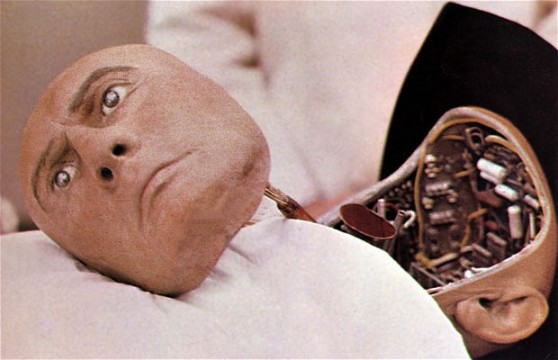

At the 4:30 mark a passage from one of the most infamous TV interviews ever, Siegel questioning a seriously inebriated Truman Capote in 1978, a time before the commodification of dysfunction was prevalent.

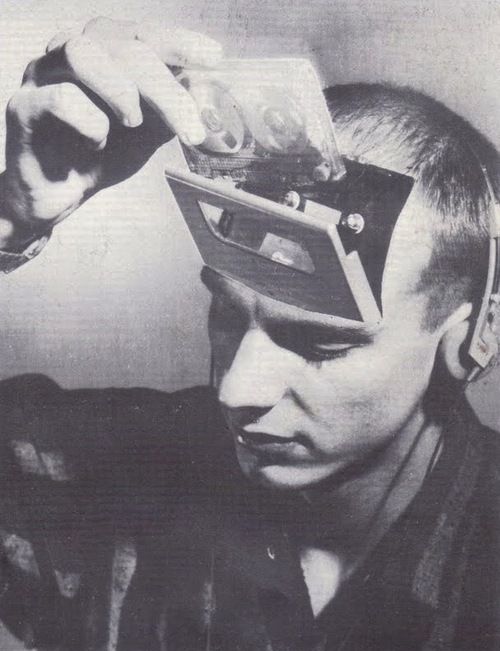

One of my favorite video clips of all time: Smartmouth Siegel interviews labia salesman Al Goldstein and comedian Jerry Lewis in 1976. When not busy composing the world’s finest beaver shots, Goldstein apparently had a newsletter about tech tools. He shows off a $3900 calculator watch and a $2200 portable phone. Lewis, easily the biggest tool on the stage, flaunts his wealth the way only a truly insecure man can.