Question:

Fintan O’Toole, in an essay that I thought was very perceptive about your work in the New York Review, wrote that in your plays darkness is inextricable from the popular entertainment – that wrapped up in the smooth consolations of prime time is a core of utter cruelty. I’m wondering, what do you think explains this relationship between entertainment and cruelty?

Wallace Shawn:

Well, cruelty is often expressed in entertainment …

Question:

Spectacle.

Wallace Shawn:

… obviously, the most famous being the Romans, who openly had people being killed in front of an audience.

Question:

Or lynching in the States, as well.

Wallace Shawn:

Yes. And, of course, public executions, which are still common in many countries. I mean, human beings have, one might say, in infinite well of sadism somewhere inside them, and our, you know, challenge is to try to prevent that from having everyone annihilate everyone else. But obviously there’s a tremendous amount of vicarious killing, beating and insulting that forms a large part of film and television entertainment. I mean, you know, you have to … you have to work hard to find popular pieces of entertainment – I mean, of television or films – that don’t contain those elements. But it’s … you know, when I was, I suppose … maybe nine or so, and my brother was five, we had a little Super 8 movie camera, and we made little films – and we were not very rough boys, to put it mildly, but we had guns and fist-fights, and our father tried to encourage us to make up a story that had no violence in it, and I think he gave us a head-start, you know, some suggestions on how to go about it.

Question:

This isn’t a violent story, but you do talk, in one of your essays, in a very affecting scene where you’re riding in a cab with your dad – I think you’re about ten years old – and you see some awkward, miserable-looking kid, and you start laughing at him, and your father breaks down in tears.

Wallace Shawn:

Well, he was a sensitive guy. And I don’t know if there’s any ten-year-old who is very sensitive – maybe there are. He was … yeah, it was a funny-looking, overweight kid who would have been, you know, bullied in school, and I didn’t know him, but I was indirectly bullying him just by laughing at his appearance. And, you know, that was a powerful lesson from my father, which, you know, one has to … I have to re-learn it all the time – certainly, as a short actor, I’m offered … well, I’m no longer offered many parts, because I’m declining in my popularity, but I … I have been, over the years, offered an enormous number of parts where my character, the short guy, is being bullied, and it’s supposed to be funny – and then, at a certain point, I sort of realised that was what it was, and started turning those down – along with the parts with the bullied short guy realises that he, too, can be a bully.

Question:

And turns his aggression against the other?

Wallace Shawn:

Exactly – maybe with a gun, or maybe through some clever tactic such as kicking him in the testicles, whatever.

Question:

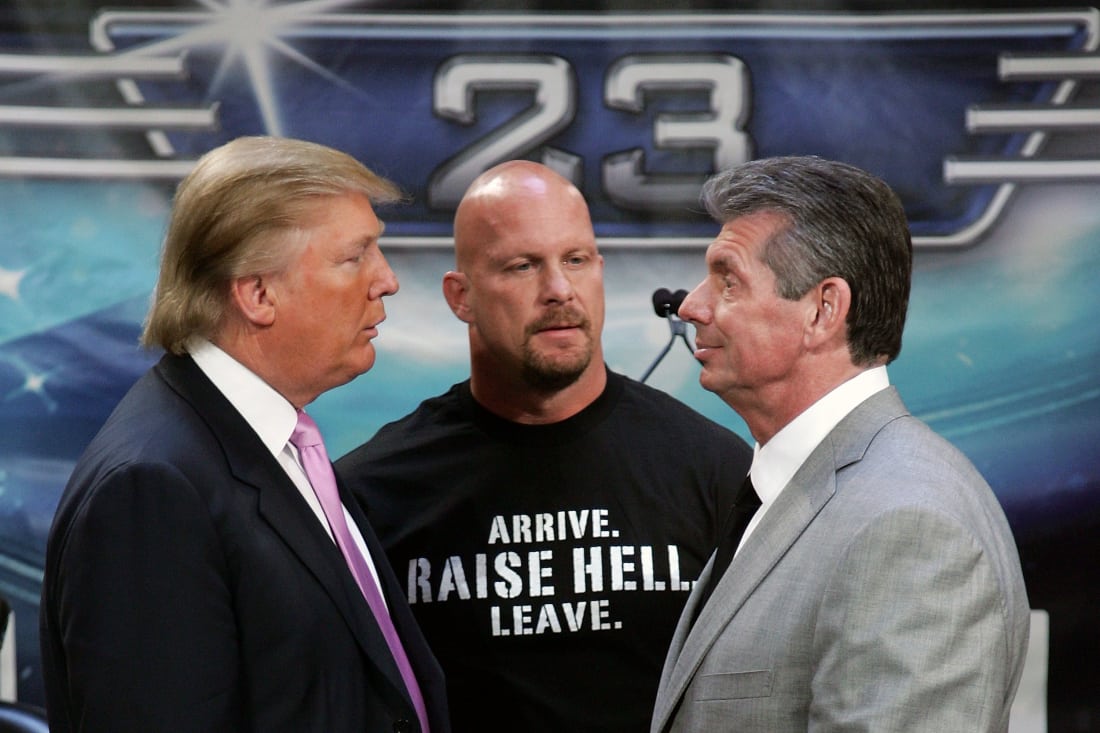

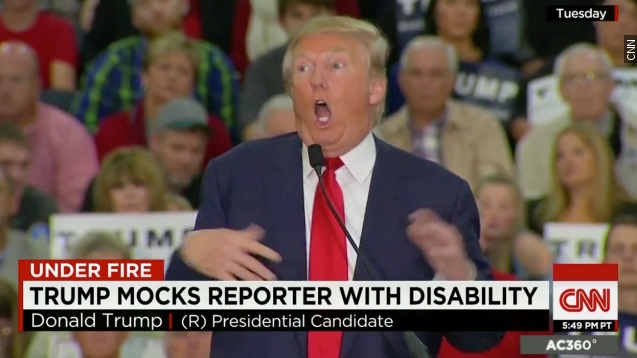

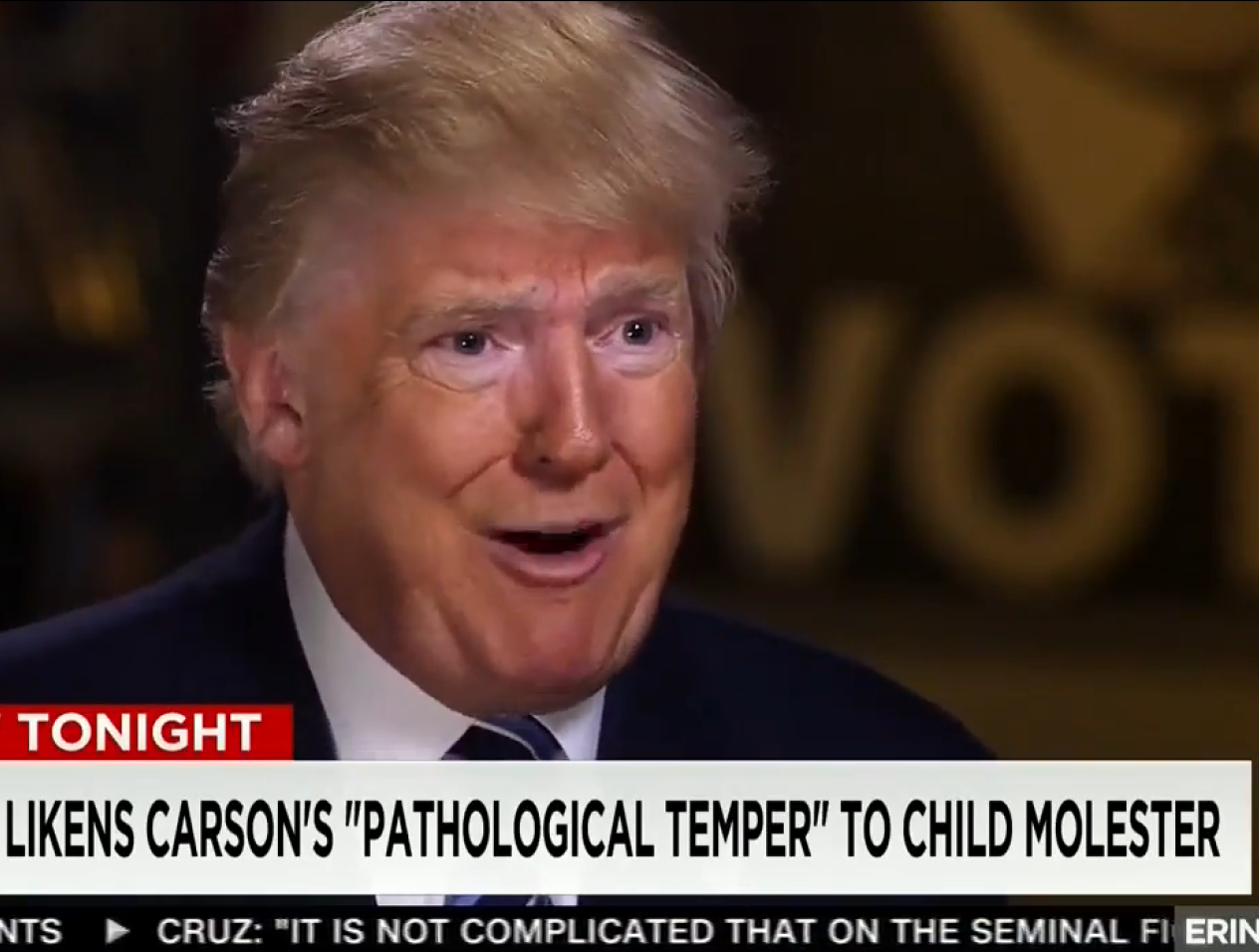

One of the things that makes your work striking and disturbing, your plays, is that you often describe the dark allure and the pleasure that people take in cruelty, and I think, for that reason, the plays are not accusatory or pious, because you’re writing about the seductions of amorality – and the seduction of amorality is a big theme, certainly, in The Designated Mourner. Do you think that this pleasure in cruelty and aggression is a big part of Trump’s appeal? You spoke about him earlier as ‘the boot’.

Wallace Shawn:

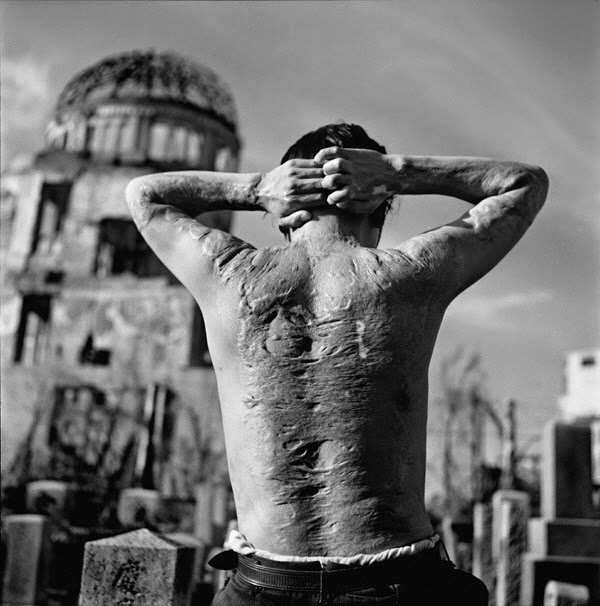

Well, I think he certainly has concluded that that is the side of him that has made him president. I personally found his speech the other day to the policemen at the Police Academy, where he said, Don’t be too nice, one of the more horrifying moments in his presidency. I think that the pleasure that people take in cruelty, or what you would call sadism, is a very under-discussed motive for a tremendous amount of what goes on in the world – not just in our country. I mean, people take at face value the verbal explanation for why someone is being beaten up or shot, or hundreds of people being beaten up or shot, or people are being are being tortured. There are a million explanations, as there have been for every war that’s ever been fought, going back to the beginning of humanity. These … you know, there are different explanations – the explanation that is ignored is the one that isn’t put into words: the human love of cruelty, the desire to kill, the desire to torment other humans – that’s not included. I mean, the Americans say, We are fighting for freedom and democracy, and the Isis people say, We’re fighting for God, and … I mean, there have been a million explanations. But there is … an irrational desire to hurt or kill other people that is, for reasons we don’t fully understand, sometimes quiet inside humans and sometimes comes to the fore.•