Does democracy know its limits?

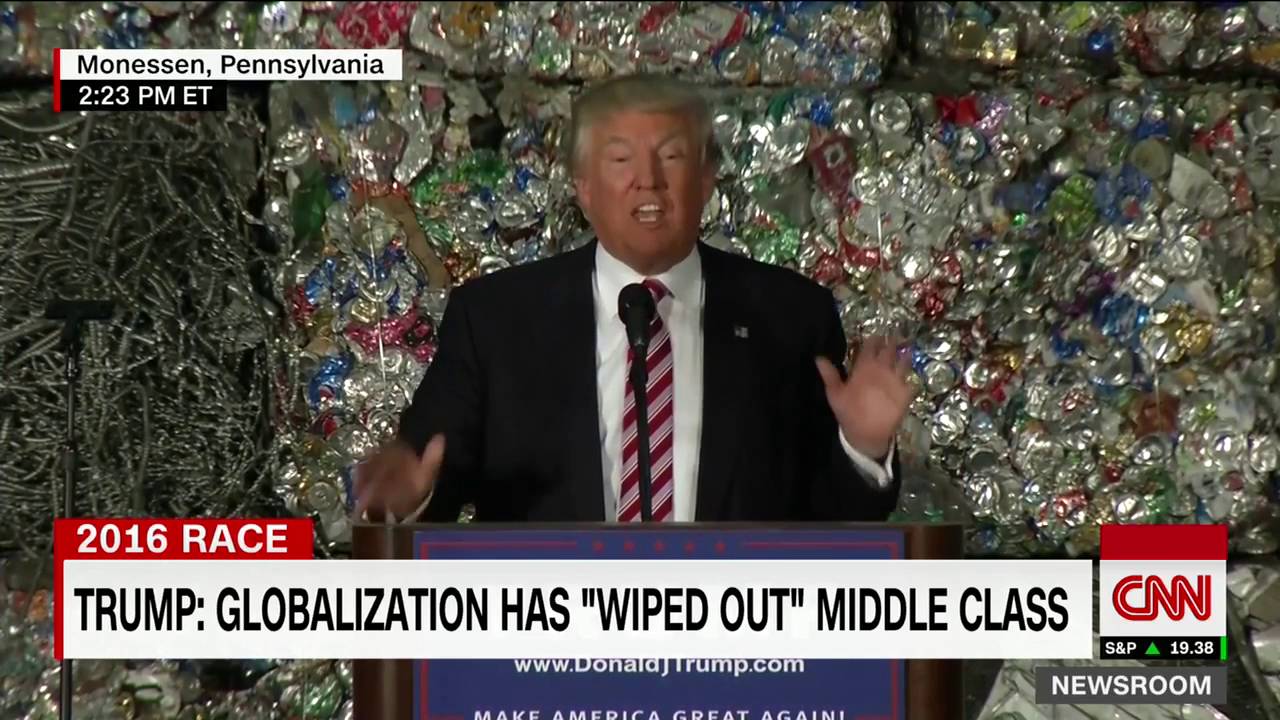

As long as Donald Trump, a preferred artist at KKK karaoke night, isn’t in the White House, America can look askance at England and its self-defeating Brexit. But what if, say, Texas had the opportunity to vote to become independent after the election or reelection of President Obama? The state may be shockingly purplish this time around, but it would have already exited the nation if such a referendum was permitted in 2008 or 2012. Direct democracy seems like such an inviting idea. Who doesn’t want more democracy? But maybe it’s best we don’t vote on everything.

Three excerpts from: 1) Michael Sauga’s Spiegel editorial about the downside of direct democracy, 2) Andrew Sullivan’s New York piece about what he feels may be democracy’s breaking point, and 3) the late Michael Kelly’s 1992 New York Times article about Ross Perot’s long-held McLuhan-ish dream of an electronic voting booth of sorts.

From Sauga:

Boris Johnson has always had a playful relationship with power. During his time at university, it is said that the conservative politician pretended to be a member of the Labour Party in order to have better chances in the student union. As a journalist, he had a penchant for criticizing EU laws that didn’t even exist. And when the world was recently left scratching its head over how Britain could have voted to leave the EU, the leader of the Brexit camp unceremoniously dismissed the historical vote by 17 million Brits as a non-event. For now, the former London mayor concluded, “nothing will change over the short term.”

The success of political gambler Johnson represents a defeat not only for supporters of the European Union in Britain, but also for those who believe in direct democracy. Even here in Germany, citizens initiatives along with a broad spectrum of political parties — from the conservative Christian Social Union to the Green Party — have supported the idea of holding the greatest possible number of referendums as an antidote to the crisis in Western parliamentarianism. The hope is that calling voters to the polls will not only bring about the purest possible expression of the electorate’s preference, but also that it will provide clarity on issues of importance and create the foundation for a new societal consensus on the strength of a majority vote. The idea is that more votes translate into more democracy.

Rarely, though, have the limitations of plebiscites been shown so clearly as in the British vote. Not because most experts believe the result to be misguided. Voters have the undeniable right to value the supposed advantages of increased sovereignty over the obvious economic and political disadvantages.•

From Sullivan:

What the 21st century added to this picture, it’s now blindingly obvious, was media democracy — in a truly revolutionary form. If late-stage political democracy has taken two centuries to ripen, the media equivalent took around two decades, swiftly erasing almost any elite moderation or control of our democratic discourse. The process had its origins in partisan talk radio at the end of the past century. The rise of the internet — an event so swift and pervasive its political effect is only now beginning to be understood — further democratized every source of information, dramatically expanded each outlet’s readership, and gave everyone a platform. All the old barriers to entry — the cost of print and paper and distribution — crumbled.

So much of this was welcome. I relished it myself in the early aughts, starting a blog and soon reaching as many readers, if not more, as some small magazines do. Fusty old-media institutions, grown fat and lazy, deserved a drubbing. The early independent blogosphere corrected facts, exposed bias, earned scoops. And as the medium matured, and as Facebook and Twitter took hold, everyone became a kind of blogger. In ways no 20th-century journalist would have believed, we all now have our own virtual newspapers on our Facebook newsfeeds and Twitter timelines — picking stories from countless sources and creating a peer-to-peer media almost completely free of editing or interference by elites. This was bound to make politics more fluid. Political organizing — calling a meeting, fomenting a rally to advance a cause — used to be extremely laborious. Now you could bring together a virtual mass movement with a single webpage. It would take you a few seconds.

The web was also uniquely capable of absorbing other forms of media, conflating genres and categories in ways never seen before. The distinction between politics and entertainment became fuzzier; election coverage became even more modeled on sportscasting; your Pornhub jostled right next to your mother’s Facebook page. The web’s algorithms all but removed any editorial judgment, and the effect soon had cable news abandoning even the pretense of asking “Is this relevant?” or “Do we really need to cover this live?” in the rush toward ratings bonanzas. In the end, all these categories were reduced to one thing: traffic, measured far more accurately than any other medium had ever done before.

And what mainly fuels this is precisely what the Founders feared about democratic culture: feeling, emotion, and narcissism, rather than reason, empiricism, and public-spiritedness. Online debates become personal, emotional, and irresolvable almost as soon as they begin. Godwin’s Law — it’s only a matter of time before a comments section brings up Hitler — is a reflection of the collapse of the reasoned deliberation the Founders saw as indispensable to a functioning republic.•

From Kelly:

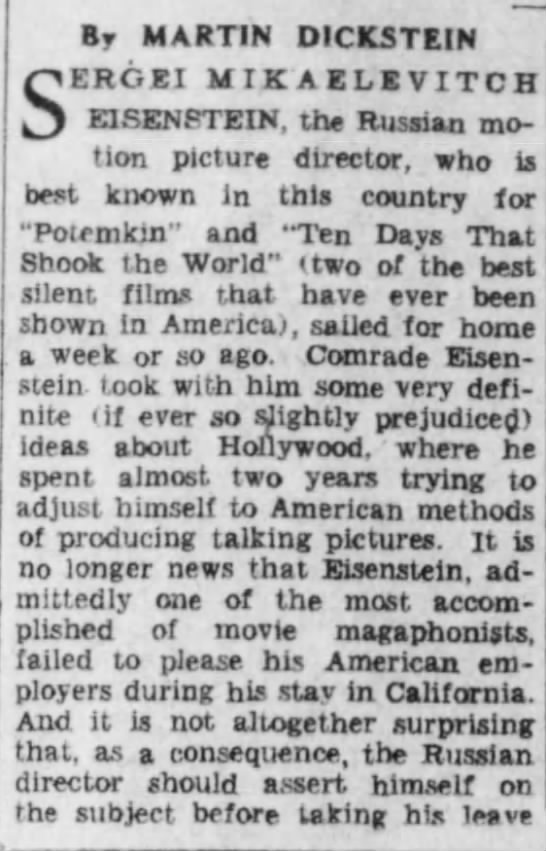

WASHINGTON, June 5— Twenty-three years ago, Ross Perot had a simple idea.

The nation was splintered by the great and painful issues of the day. There had been years of disorder and disunity, and lately, terrible riots in Los Angeles and other cities. People talked of an America in crisis. The Government seemed to many to be ineffectual and out of touch.

What this country needed, Mr. Perot thought, was a good, long talk with itself.

The information age was dawning, and Mr. Perot, then building what would become one of the world’s largest computer-processing companies, saw in its glow the answer to everything. One Hour, One Issue

Every week, Mr. Perot proposed, the television networks would broadcast an hourlong program in which one issue would be discussed. Viewers would record their opinions by marking computer cards, which they would mail to regional tabulating centers. Consensus would be reached, and the leaders would know what the people wanted.

Mr. Perot gave his idea a name that draped the old dream of pure democracy with the glossy promise of technology: “the electronic town hall.”

Today, Mr. Perot’s idea, essentially unchanged from 1969, is at the core of his ‘We the People’ drive for the Presidency, and of his theory for governing.

It forms the basis of Mr. Perot’s pitch, in which he presents himself, not as a politician running for President, but as a patriot willing to be drafted ‘as a servant of the people’ to take on the ‘dirty, thankless’ job of rescuing America from “the Establishment,” and running it.

In set speeches and interviews, the Texas billionaire describes the electronic town hall as the principal tool of governance in a Perot Presidency, and he makes grand claims: “If we ever put the people back in charge of this country and make sure they understand the issues, you’ll see the White House and Congress, like a ballet, pirouetting around the stage getting it done in unison.”

Although Mr. Perot has repeatedly said he would not try to use the electronic town hall as a direct decision-making body, he has on other occasions suggested placing a startling degree of power in the hands of the television audience.

He has proposed at least twice — in an interview with David Frost broadcast on April 24 and in a March 18 speech at the National Press Club — passing a constitutional amendment that would strip Congress of its authority to levy taxes, and place that power directly in the hands of the people, in a debate and referendum orchestrated through an electronic town hall.•