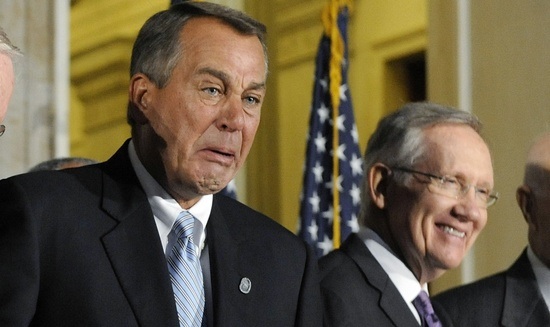

One of the more awful things about the current (and manufactured) American economic crisis is that it has nothing to do with economics. Republicans will say that they’re shutting down the government to force spending cuts to correct long-tern budget deficits. Except that there likely are no long-term budget deficits, and a little more government investment would probably make that certain. This conflict is driven rather by ideology; it’s about wanting to enact punitive measures against our most vulnerable people to teach them a lesson of some sort. The opening of “The Battle Over the US Budget Is the Wrong Fight,” a new Lawrence Summers piece in the Financial Times:

“This month Washington is consumed by the impasse over reopening the government and raising the debt limit. It seems likely that this episode, like the 1995-96 government shutdowns and the 2011 debt limit scare, will be remembered mainly by the people directly involved. But there is a chance future historians will see today’s crisis as the turning point when American democracy was to shown to be dysfunctional – an example to be avoided rather than emulated.

The tragedy is compounded by the fact that most of the substance being debated in the current crisis is only tangentially relevant to the main challenges and opportunities facing the country. This is the case with respect to the endless discussions about the precise timing of continuing resolutions and debt limit extensions, and to the proposals to change congressional staff healthcare packages and cut a medical device tax that represents only about 0.015 per cent of gross domestic product.

More fundamental is this: budget deficits are now a second-order problem relative to more pressing issues facing the US economy. Projections that there is a major deficit problem are highly uncertain. And policies that indirectly address deficit issues by focusing on growth are sounder economically and more plausible politically than the long-term budget deals with which much of the policy community is obsessed.”