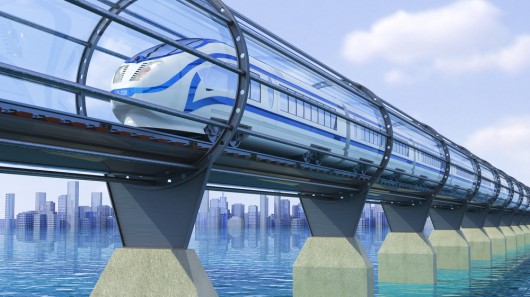

A manufacturing job can disappear, an autonomous machine replacing a human worker, but will people invite the transition, will they hand over the wheel? The technology for driverless cars is close, but questions remain, both legal and practical. In the latter category: Driverless vehicles are so good environmentally because they crash so infrequently that they can be far lighter which means they’ll require less fuel. But how can cars be made so lightweight if we’re still split between autonomous vehicles and human-guided ones? From Kevin Robillard at Politico:

“Driverless cars are poised to begin transforming the nation’s roadways before the end of the decade, a major transportation group said Wednesday, but a top federal transportation official warned things might not be so easy.

The Eno Center for Transportation released a paper that predicted a nation full of driverless ‘autonomous’ vehicles could save $447 billion and 21,700 lives annually by preventing 4.2 million crashes and reducing fuel consumption by 724 million gallons. Still, switching from highways full of drivers to highways full of computers won’t be simple.

‘We’re looking at the introduction of AVs by the end of the decade,’ Daniel Fagnant, the paper’s author, said at an event Wednesday.

The switch to autonomous vehicles comes with enough potential benefits to make transportation policymakers giddy. Computers don’t get drunk, fall asleep or get distracted by text messages. They can stay a precise distance away from the car in front of them, reducing time and fuel wasted by congestion.

The headache comes in getting there.”