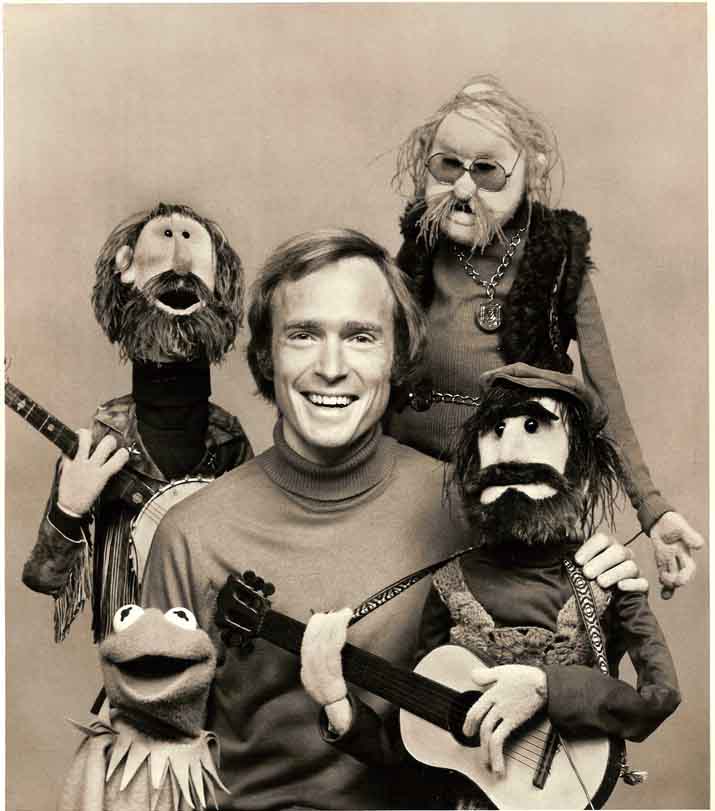

John Adams wasn’t thinking specifically of technology when he said the following, but he might as well have been: “I must study politics and war, that my sons may have the liberty to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, and naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture, in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain.”

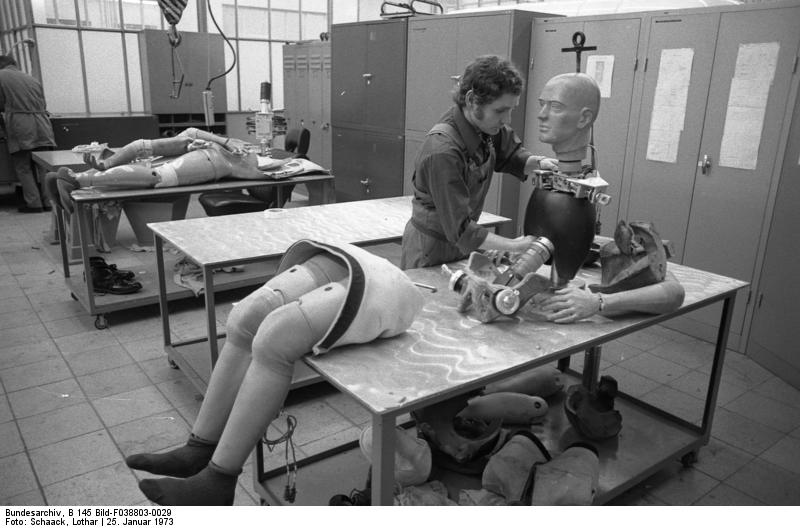

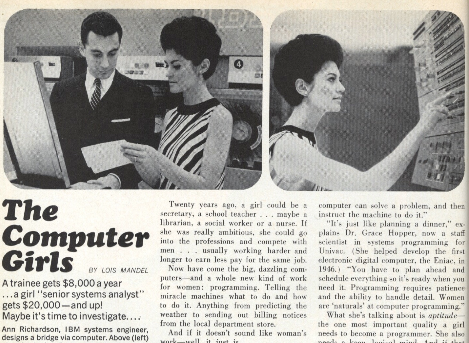

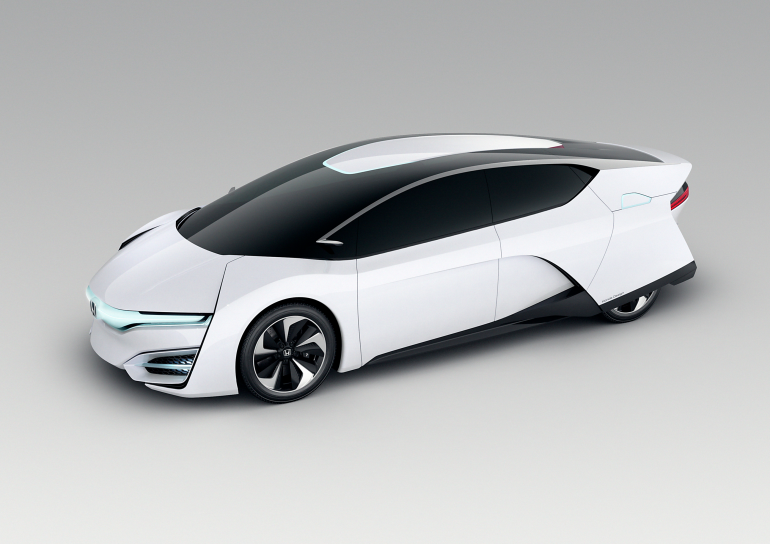

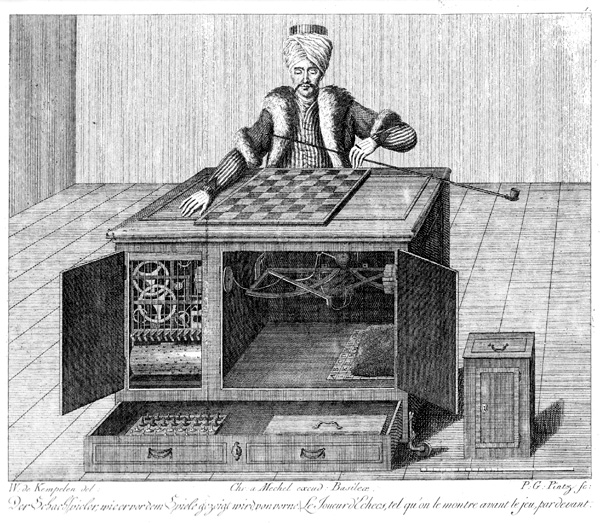

Eventually, and not too far off in the future, Amazon won’t need any human pickers to pull items from their inventory shelves, 3-D printers will allow ideas to spring fully grown from our heads and no one will have much use for a human taxi driver. It will all be AI. That’s great, though it does pose some new problems. Chiefly, how do we reconcile what’s largely a free-market economy with one that’s “post-jobs” to a certain degree, at least if we’re talking about the type of traditional work that our society is built on? We may become wealthier as a people, but how does that wealth reach the people? That could make for a messy transition, and to some extent it already has. Another question is what do we do with ourselves if toil is a thing of the past, and other challenges we thought were our own are assumed by silicon?

From Ray Kurzweil’s site, an exchange between a reader and the futurist about molecular assemblers, which may take building out of our hands, freeing them perhaps for painting and statuary but more likely for some yet unknown tasks:

“Question:

Suppose molecular assemblers are indeed proven to be feasible on a large scale and we are given an infinite abundance to produce as much as we want — limited only by the amount of matter in our vicinity — with minimal effort.

If this scenario comes to fruition, how will humans be able to cope with the lack of challenges in their lives? It seems like with assemblers there will be very little incentive to do anything.

Since everything could be obtained effortlessly through assemblers, there appears to be little purpose to hold a job, since all possessions could be obtained for free.

Ray Kurzweil:

Future molecular assemblers will make physical things, but not create new knowledge.

We are doubling knowledge about every year and that will remain a challenge requiring increasing levels of intelligence.”