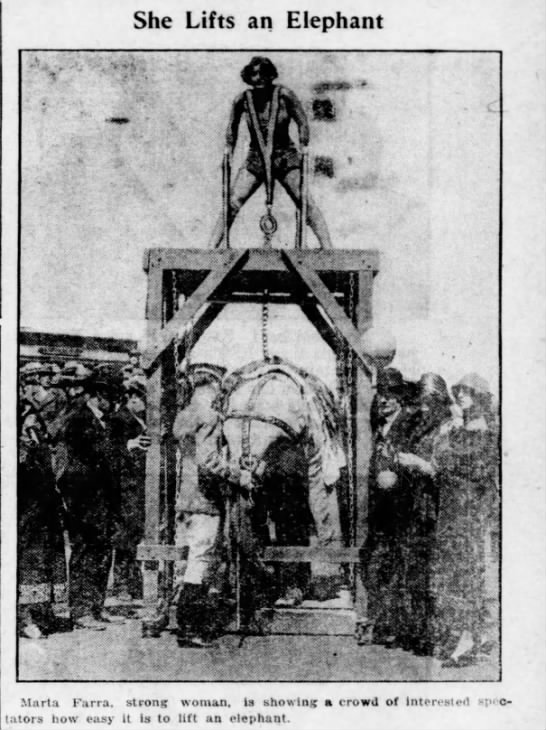

From the April 10, 1924 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Tags: Marta Farra, Martha Cohen, Martha Farra

Anti-Semitism, racism, sexism, xenophobia, Islamophobia and other evils have been ushered into the mainstream by the opportunists and hatemongers who helped enable Donald Trump into the Oval Office, and it makes no difference that some of them fall into the very groups now being targeted (Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump and Stephen Miller, namely).

In the early days of the GOP nomination process, when it seemed done deal that Donald Trump would soon fall from the race after disgracefully gaining attention for his idiotic “brand,” Edward Luce of the Financial Times warned that even if the Mussolini-Lampanelli madman fell from the sky, the dark clouds that had formed would not go away. They would spread, becoming more ominous.

Then the worst of all possible outcomes occurred when Trump won the Electoral College, with the aid of Putin, Comey, neo-Nazis and so-called geniuses like Peter Thiel and David Gelernter. Now we have Indian people shot in Kansas, bigoted domestic terrorists arrested for murderous plots and Jewish cemeteries desecrated. Meanwhile, international scholars are interrogated at airports and undocumented workers flee for the Canadian border, willing to sacrifice fingers and toes to frostbite. That’s the nightmare version of America–the un-America.

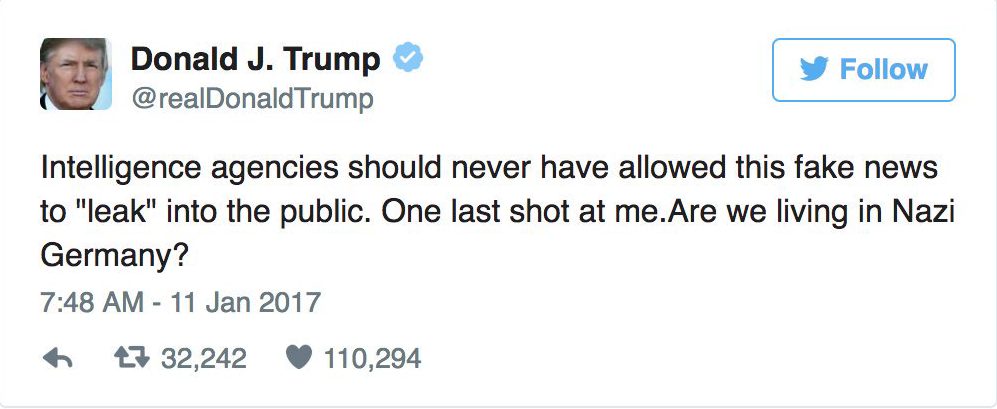

So far, citizens, journalists, judges and the Intelligence Community have stood tall against the threat of tyranny, while the opportunists and regressive minds in the legislature have performed as poorly as has been expected. Trump has targeted news organizations with the zeal of Putin and Erdogan because his type of hatred exists like a barnacle on the back of a created enemy and because the truth is not his friend.

From Klaus Brinkbäumer in Spiegel:

In Trump’s America, meanwhile, the press has been declared an “enemy of the people.” “You are fake news,” the president says when he sees a CNN reporter. A colleague at The Washington Post recently shared how the White House no longer answers any of his questions, only to then start blasting insults every time a story is published. It isn’t until that point that the president’s spokesman actually bothers to return his call, but only to say, “Fuck you, asshole. We’re going to make your life hell.” The effect of all of this is that truth and lies are getting blurred, the public is growing disoriented and, exhausted, it is tuning out.

This, in turn, aids the wrong people. Erdogan and Trump are positioning themselves as the only ones capable of truly understanding the people and speaking for them. It’s their view that freedom of the press does not protect democracy and that the press isn’t reverent enough to them and is therefore useless. They believe, after all, that the words that come from their mouths as powerful leaders are the truth and that the media, when it strays from them, is telling lies. That’s autocratic thinking — and it is how you sustain a dictatorship.

The idea of freedom of speech first came into being hundreds of years ago. The poet John Milton issued a plea for the “liberty of unlicensed printing” in 1644. “The destruction of a good book ends not in the slaying of an elemental life,” he wrote, “but strikes at that ethereal and fifth essence, the breath of reason itself.” The seed had been planted and England moved to eliminate censorship in 1695. In 1776, the state of Virginia in the United States established the freedom of the press in America. The move was bold, enlightened and precious, making it that much more astonishing that some Turks and Americans now allow themselves to be lied to or have simply become too lazy to think critically.•

Tags: Donald Trump, Klaus Brinkbäumer

Bill Gates just conducted one of his wide-ranging Reddit AMAs, touching base on Guaranteed Basic Income, philanthropy, neuroscience, etc.

Like Mark Zuckerberg, who seems to be basing his development as a businessperson and public person on the Gates template, the Microsoft founder says he hopes that digital tools can help bring more citizens together without mentioning that some of these people will form horrible and dangerous blocs. It sure seems like we were better off before fringe Americans–conspiracists, new-wave KKKs and kooks of every stripe–were able to congregate online and form cohesive national movements that could push the agenda into dark corners, especially in a time of dramatic wealth inequality, when billionaires like Robert Mercer can fund hatemongers and fuel disinformation.

A few exchanges follow.

Question:

Any thoughts on the current state of the U.S.?

Bill Gates:

Overall like Warren Buffett I am optimistic about the long run. I am concerned in the short run that the huge benefits of how the US works with other countries may get lost. This includes the aid we give to Africa to help countries there get out of the poverty trap.

Question:

I have a question pertaining to an issue in the U.S. and it’s one that we’re all get sick of hearing.

Do you think social media – and perhaps the internet in general – has played a role in helping divide this country?

Instead of expanding knowledge and obtaining greater understandings of the world, many people seem to use it to

1) seek and spread information – including false information – confirming their existing biases and beliefs, and

2) converse and interact only with others who share their worldview (these are things I’m guilty of doing myself)

Bill Gates:

This is a great question. I felt sure that allowing anyone to publish information and making it easy to find would enhance democracy and the overall quality of political debate. However the partitioning you talk about which started on cable TV and might be even stronger in the digital world is a concern. We all need to think about how to avoid this problem. It would seem strange to have to force people to look at ideas they disagree with so that probably isn’t the solution. We don’t want to get to where American politics partitions people into isolated groups. I am interested in anyone’s suggestion on how we avoid this.

Question:

What do you think is the most pressing issue that we could feasibly solve in the next ten years?

Bill Gates:

A lot of people feel a sense of isolation. I still wonder if digital tools can help people find opportunities to get together with others – not Tinder but more like adults who want to mentor kids or hang out with each other. It is great that kids go off and pursue opportunities but when you get communities where the economy is weak and a lot of young people have left then something should be done to help.

Question:

What kind of technological advancement do you wish to see in your lifetime?

Bill Gates:

The big milestone is when computers can read and understand information like humans do. There is a lot of work going on in this field – Google, Microsoft, Facebook, academia,… Right now computers don’t know how to represent knowledge so they can’t read a text book and pass a test.

Another whole area is vaccines. We need a vaccine for HIV, Malaria and TB and I hope we have them in the next 10-15 years.

Question:

If you could give 19 year old Bill Gates some advice, what would it be?

Bill Gates:

I would explain that smartness is not single dimensional and not quite as important as I thought it was back then. I would say you might explore the developing world before you get into your forties. I wasn’t very good socially back then but I am not sure there is advice that would fix that – maybe I had to be awkward and just grow up….

Question:

If you could create a new IP and business with Elon Musk, what would you make happen?

Bill Gates:

We need clean, reliable cheap energy – which we don’t have. It is too bad the sun doesn’t shine all the time and the wind doesn’t blow all the time. The Economist had a good piece on this this week. So we need some invention – perhaps miracle batteries or super safe nuclear or making sun into gasoline directly.

Question:

What are the limits of money when it comes to philanthropy?

Bill Gates:

Philanthropy is small as a part of the overall economy so it can’t do things like fund health care or education for everyone. Government and the private sector are the big players so philanthropy has to be more innovative and fund pilot programs to help the other sectors. A good example is funding new medicines or charter schools where non-obvious approaches might provide the best solution.

One thing that is a challenge for our Foundation is that poor countries often have weak governance – small budgets, and the people in the ministries don’t have much training. This makes it harder to get things done.

If we had more money we could do more good things – even though we are the biggest foundation we are still resource limited.

Question:

What do you think about Universal Basic Income?

Bill Gates:

Over time countries will be rich enough to do this. However we still have a lot of work that should be done – helping older people, helping kids with special needs, having more adults helping in education. Even the US isn’t rich enough to allow people not to work. Some day we will be but until then things like the Earned Income Tax Credit will help increase the demand for labor.

Question:

What are you most curious about, Bill?

Bill Gates:

I still find the creation of life and the way the brain works the most fascinating areas. Nick Lane has some great books exploring what we know about how life started. It is amazing how little we know about the brain still but I expect we will know a lot more in 10 years.•

Tags: Bill Gates

In a vital Guardian article that ties together online-media manipulation, psychological profiling of voters, Trump and Brexit, reporter Carole Cadwalladr follows a byzantine trail that leads to the right-wing machinations of computer scientist and billionaire Robert Mercer, the single biggest donor in the 2016 U.S. Presidential race.

Mercer, an old friend of fellow anti-government zealots Steve Bannon and Nigel Farage, has often futilely thrown money at his ultra-conservative causes, but when you have that much to wager, you can keep trying until you break the bank. In 2016, he did just that.

The Renaissance Technologies CEO offered the services of data research firm Cambridge Analytica to both Trump and Leave.EU, which helped them game Facebook and Google in a large-scale way, create extensive individual profiles of citizens and destabilize genuine journalism. It permitted mud to be thrown with precision on both sides of the pond, creating propaganda to fit the Digital Age. As a ranking member of Leave.EU tells the Guardian: “What they were trying to do in the US and what we were trying to do had massive parallels.”

Mark Zuckerberg wants us to believe that Facebook, despite its many failings, should play a leading role in saving global democracy, but who will save it from Facebook?

From Cadwalladr:

Which is how, earlier this week, I ended up in a Pret a Manger near Westminster with Andy Wigmore, Leave.EU’s affable communications director, looking at snapshots of Donald Trump on his phone. It was Wigmore who orchestrated Nigel Farage’s trip to Trump Tower – the PR coup that saw him become the first foreign politician to meet the president elect.

Wigmore scrolls through the snaps on his phone. “That’s the one I took,” he says pointing at the now globally famous photo of Farage and Trump in front of his golden elevator door giving the thumbs-up sign. Wigmore was one of the “bad boys of Brexit” – a term coined by Arron Banks, the Bristol-based businessman who was Leave.EU’s co-founder.

Cambridge Analytica had worked for them, he said. It had taught them how to build profiles, how to target people and how to scoop up masses of data from people’s Facebook profiles. A video on YouTube shows one of Cambridge Analytica’s and SCL’s employees, Brittany Kaiser, sitting on the panel at Leave.EU’s launch event.

Facebook was the key to the entire campaign, Wigmore explained. A Facebook ‘like’, he said, was their most “potent weapon”. “Because using artificial intelligence, as we did, tells you all sorts of things about that individual and how to convince them with what sort of advert. And you knew there would also be other people in their network who liked what they liked, so you could spread. And then you follow them. The computer never stops learning and it never stops monitoring.”

It sounds creepy, I say.

“It is creepy! It’s really creepy! It’s why I’m not on Facebook! I tried it on myself to see what information it had on me and I was like, ‘Oh my God!’ What’s scary is that my kids had put things on Instagram and it picked that up. It knew where my kids went to school.”

They hadn’t “employed” Cambridge Analytica, he said. No money changed hands. “They were happy to help.”

Why?

“Because Nigel is a good friend of the Mercers. And Robert Mercer introduced them to us. He said, ‘Here’s this company we think may be useful to you.’ What they were trying to do in the US and what we were trying to do had massive parallels. We shared a lot of information. Why wouldn’t you?” Behind Trump’s campaign and Cambridge Analytica, he said, were “the same people. It’s the same family.”•

10 search-engine keyphrases bringing traffic to Afflictor this week:

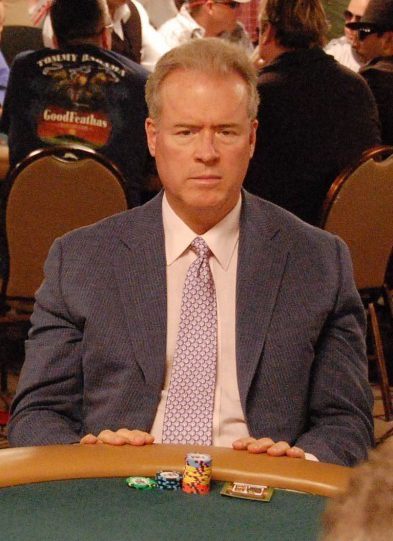

- legendary film producer robert evans

- phone numbers resemble gene sequences

- new hate groups like the kkk

- human cannonballs

- late talk show host stanley siegel

- our minds connected to devices

- tad friend profile of sam altman

- oldest man in the world

- aubrey de grey creating immortality

- russian politician vladimir kara-murza poisoned

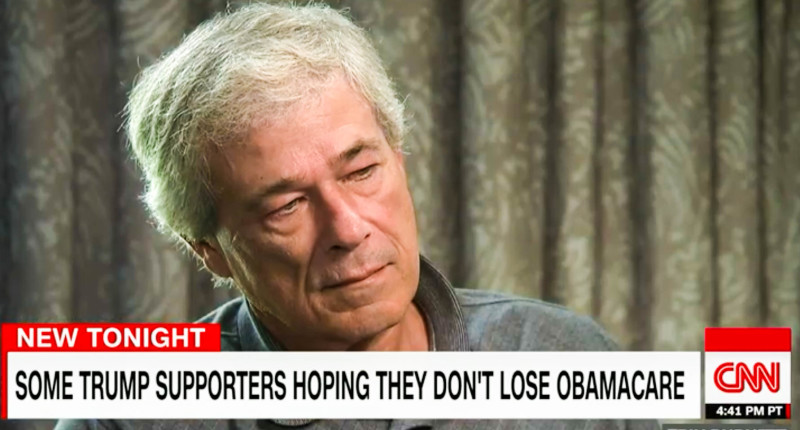

This week, it became apparent to Trump voters they may lose their Obamacare, though I’m sure the doctors they’ll be able to afford without it will be fine.

- An Ahab’s in the Oval Office and the ship is in trouble, writes Eliot A. Cohen.

- Henry Ford was as bigoted as the Andrew “Dice” Jackson who’s now President.

- Trump’s manipulation of CEA numbers is intellectually dishonest.

- Tim Wu did an AMA that covered net neutrality in the time of the Trump.

- In 1952, Alistair Cooke worried about tyranny in a post-newsprint age.

- Lawrence Summers discusses globalization and social insurance.

- Walter Scheidel writes of the high price of combating wealth inequality.

- Luciano Floridi analyzes addressing inequality through taxing robots.

- A NYT editorial tackles robotics and the American Dream has some blind spots.

- Philosopher David Chalmers conducted an AMA on consciousness + technology.

- Nicholas Carr responds to Mark Zuckerberg’s “Building Global Community.”

- Laurie Penny says the climate-change apocalypse will be unevenly distributed.

- In addition to the huge moral failing, Muslim bans are terrible for the economy.

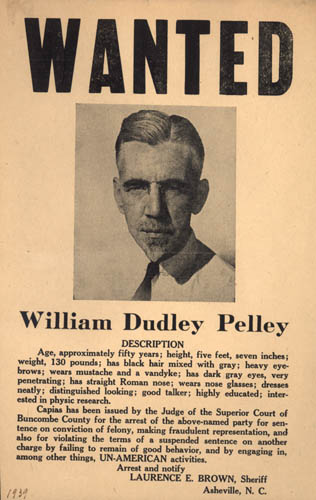

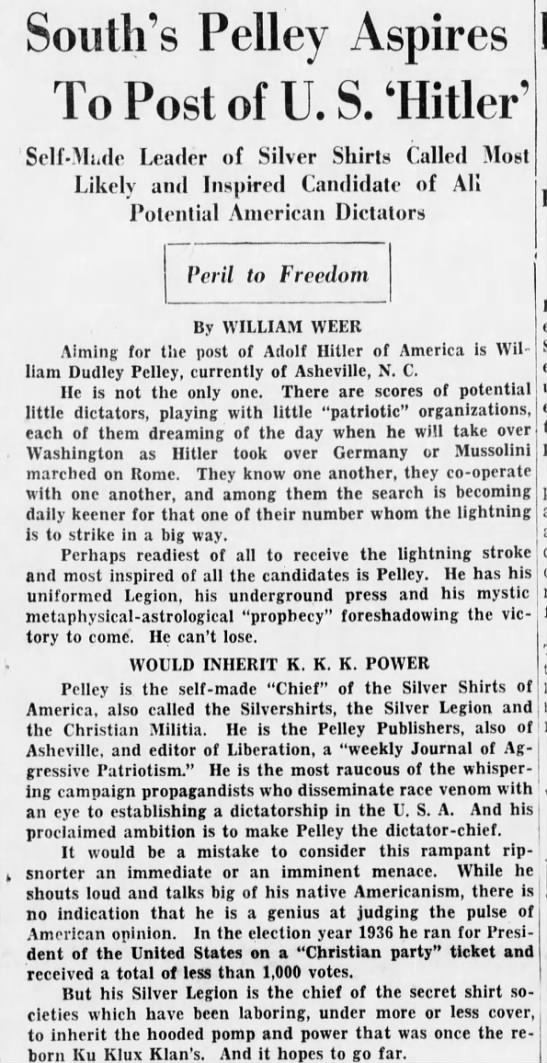

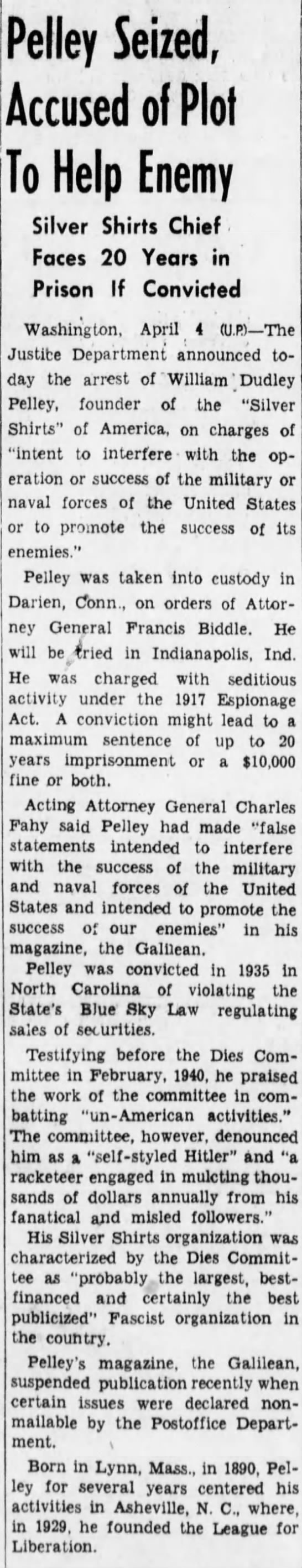

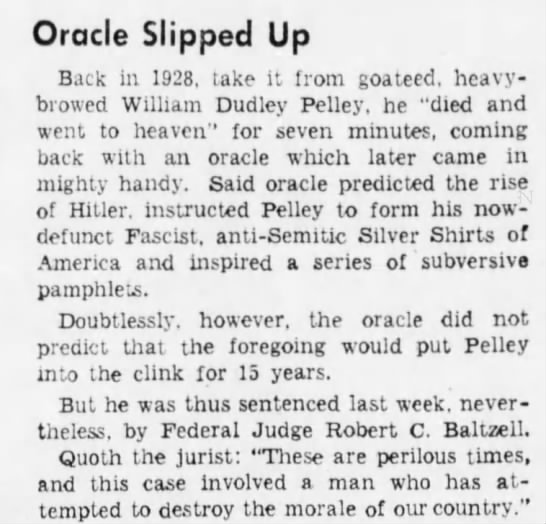

- Old Print Article: William Dudley Pelley, an American Hitler. (1938/42)

- A brief note from 1934 about Fascist mass weddings.

- This week’s Afflictor keyphrase searches: Donald Rumsfeld, Brexit, etc.

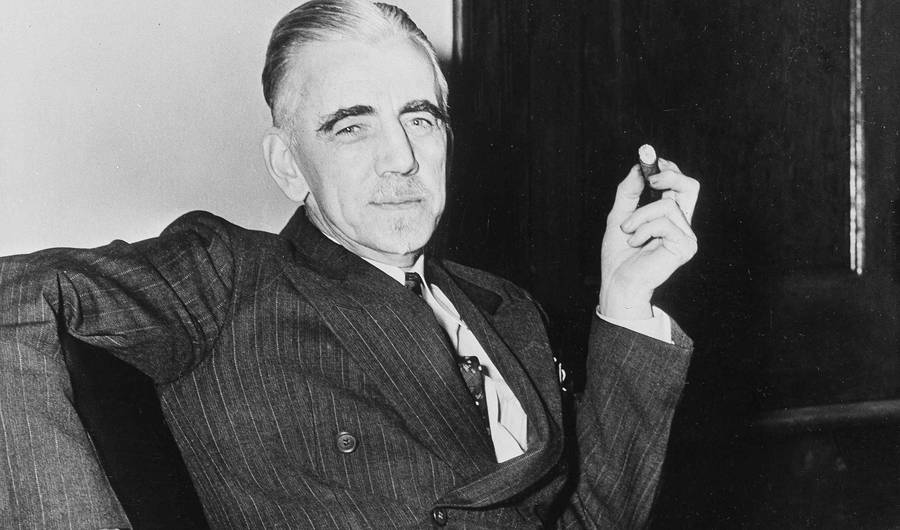

Karl Marx wrote that “history repeats…first as tragedy, then as farce,” but when it comes to the threat of Fascism in America over the last century, the order, it would seem, has been reversed.

William Dudley Pelley was a white supremacist and Hitler wannabe with a missionary’s zeal when he ran for President in 1936, his risible campaign ultimately receiving a grand total of 1,600 votes. He spent most of the next decade in prison having been tried for and convicted of conspiring with the enemy during World War II.

Things didn’t start out so haywire for Pelley. An autodidact, he became a successful writer of fiction and nonfiction, even penning scenarios for silent films for Lon Chaney. In 1928, however, he claimed to have had an “out-of-body experience” in which God and Christ, performing in a duet, instructed the scribe to bring about a spiritual transformation in America, one which was to occur at the expense of Jewish and non-white people. He formed a militia of “Silver Shirts” and commenced to work which never, thankfully, proved successful.

Eighty years later, an aspiring autocrat and bigot received nearly 63 million votes, winning the Presidency by hook and by crook. Many scholars advise that Trump, for all his bad qualities, is not actually what would historically be called a Fascist. In December 2015, during the ugly-as-sin campaign, UK historian Matthew Feldman commented on the “F” word in an interview with Mic:

There are some [Fascist-sounding] things about Trump when seen in a particular light, such as his slogan, “Make America Great Again.” But what I really want to stress is that’s not the same thing as overthrowing liberal democratic regimes, which is really the hallmark of classic fascist movements.•

After all that’s transpired since the inauguration, including Trump and Steve Bannon’s words at this week’s CPAC Conference, it’s fair to fear the Administration intends to implode our liberal democratic regime from the inside. The President continued his all-out warfare on the free press, which has been one of his main targets along with the Judiciary and the Intelligence Community, while Bannon explicitly acknowledged heads of cabinets have been selected based on their ability to destroy them, to “deconstruct the administrative state.”

Even if the new boss doesn’t meet the precise specifications of traditional Fascism, elements of that system can be mixed with the new abnormal to bring about the same end. The risk of American autocracy is not a punchline now, but a series of punches. One way or another, it seems like it will all end in tragedy. It already has, really.

The following are a series of articles about Pelley from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

From April 5, 1938:

From April 5, 1942:

From August 16, 1942:

Tags: William Dudley Pelley

Tim Wu, the Columbia law professor who coined the term “network neutrality” and recent candidate for New York State Lieutenant Governor, just conducted a predictably intelligent and engaging Reddit Ask Me Anything.

Net neutrality, which was supported by the FCC during the Obama Administration, is likely on the chopping block with all three branches of the government in the hands of Republicans, and often extremely conservative ones at that.

Regardless of what happens in the immediate future, it’s still an idea that makes sense if we are to be a democracy with equal opportunities for all. Just imagine if there were two national highway systems, one that allowed 55 mph for those that can pay more and another that permitted 25 mph for those who were poor. While airlines offer different options–first class, business class, coach–everyone arrives at the same time. If we’re not all permitted a roughly similar ETA at reasonable cost, the inequality we’re now experiencing will only grow.

A few exchanges follow.

Question:

Do you have (in your mind’s eye) a moment when American society reached it’s proverbial “fork in the road” leading us on this dark path?

Tim Wu:

That is an interesting question. There is a danger in always thinking that previous times were “golden” and now is dark. Nonetheless I do think now has an objective sense of darkness, where fear and loathing seem to be the currency of daily life.

On the question of whether America took a fork in the road. Here are a few candidates, one public one private:

In the 1990s, when progressives (myself included) were too sanguine about the effects of trade, various forms of deregulation and other policies on the middle and working classes. It was predicted and well known that inequality would result, but the argument that we needed a bigger pie that could then be redistributed. The redistribution never came. And led to the election of a demagogue.

Private: The 1980s – 90s, when corporate leadership at large lost any sense of noblese oblige — a duty to the country and began to feel that their only real duties were to shareholders and maximization of executive compensation. I think this also led us to mass inequality, which I see as the root cause of most of what ails us today.

Question:

With a Republican in the White House, one would assume antitrust enforcement is dead, but Trump seems to be far more interventionist (starting trade wars, threatening private enterprises who cut jobs, etc) than traditional hands-off-the-market, laissez faire Republicans. Meanwhile, Obama’s own Council of Economic Advisors conceded the US economy became more concentrated under his watch. Do you think antitrust could actually improve under Trump? If possible, please break out your prognosis for both the US economy at large vs the internet economy.

Tim Wu:

It is hard to predict anything related to Trump. My main fear is that if there is more enforcement, that it is arbitrary and capricious, based on the beefs the administration has with its perceived enemies.

There is some sense, already, that Trump wants to use the Time – AT&T proposed merger to “punish” CNN — have it sold to someone who will do what he says. This is not the kind of antitrust policy that I support.

Question:

Do you think net neutrality can be reinstated if it’s lost or will it be near impossible to reinstate?

Tim Wu:

The idea will always be around.

Question:

Do you also want to make it illegal for UPS and Amazon to offer priority mail at a premium?

Tim Wu:

As it stands, premium delivery is a user-selected option that does not strike me as a major factor in competition among the vendors of goods

I would be concerned if…

(1) If there were evidence of limited bandwidth capacity in the delivery system, and evidence that UPS wanted to slow down mail generally to promote their “premium product” (2) If UPS and Amazon charged vendors, not consumers, to have things delivered faster (i.e., charged Fischer Price to deliver toys faster than its rivals) (3) If there was a sense that Amazon / UPS were likely to use premium mailing to entrench a monopoly incumbent (4) If premium mailing had a discernible effect on the quality of the product once it arrived.•

Tags: Tim Wu

In America, quantity matters.

Peter Thiel’s billions has impressed all manner of serious people, economists and social scientists and politicos, dollar signs making them somehow ignore that this “genius” was sure that there were WMDs in Iraq and certain that an unqualified sociopath should lead the nation. He may be smart about business, but he’s stupid about life, and it’s the kind of stupid that can get people killed. Thiel’s a rich man and a poor one.

His fellow Silicon Valley billionaire Mark Zuckerberg is also sanctified for large numbers. Not only does he have oodles of money, but reportedly close to two billion people are active on Facebook, that quasi-nation, which is part surveillance state and also the world’s largest sweatshop.

Despite years of dubious business moves, comments and “social experiments,” Zuckerberg may not be a bad person, but he also isn’t necessarily a wise one, despite what the shallowest of scoreboards may say. His recent religious revival and 50-state “listening tour” provoked speculation that he’d watched another (perhaps) billionaire celebrity snake his way into the Oval Office and decided he wanted to get into the game. He certainly would be better than Trump, but maybe we should actually elect someone who’s qualified?

But why settle for a petty bureaucrat’s position like President when you can lord over a multi-national empire?

In Zuckerberg’s recent 5,700-word position paper, “Building Global Community,” he asserts that his company must lead the way in building an Earth-sized social fabric, something that doesn’t take into consideration that a) many of us want no part of Facebook, b) many of the users possess bigoted and anti-social views, c) having for-profit companies play such a role is huge potential for abuses and d) there’s no substitute for good government or actual (rather than virtual) political movements. Moreover, social media is as much a bane to democracy as a boon–and that may be a hopeful reading of its effects–so such an initiative may be akin to treating a poisoning victim with more poison.

The opening of Nicholas Carr’s outstanding Rough Type post about the Facebook founder’s massive missive, which eviscerates its “self-serving fantasy about social relations”:

The word “community” appears, by my rough count, 98 times in Mark Zuckerberg’s latest message to the masses. In a post-fact world, truth is approached through repetition. The message that is transmitted most often is the fittest message, the message that wins. Verification becomes a matter of pattern recognition. It’s the epistemology of the meme, the sword by which Facebook lives and dies.

Today I want to focus on the most important question of all: are we building the world we all want?

It’s a good question, though I’m not sure there is any world that we all want, and if there is one, I’m not sure Mark Zuckerberg is the guy I’d appoint to define it. And yet, from his virtual pulpit, surrounded by his 86 million followers, the young Facebook CEO hesitates not a bit to speak for everyone, in the first person plural. There is no opt-out to his “we.” It’s the default setting and, in Zuckerberg’s totalizing utopian vision, the setting is hardwired, universal, and nonnegotiable.

Our greatest opportunities are now global — like spreading prosperity and freedom, promoting peace and understanding, lifting people out of poverty, and accelerating science. Our greatest challenges also need global responses — like ending terrorism, fighting climate change, and preventing pandemics. Progress now requires humanity coming together not just as cities or nations, but also as a global community. …

Facebook stands for bringing us closer together and building a global community. When we began, this idea was not controversial.

The reason the idea — that community-building on a planetary scale is practicable, necessary, and altogether good — did not seem controversial in the beginning was that Zuckerberg, like Silicon Valley in general, operated in a technological bubble, outside of politics, outside of history. Now that history has broken through the bubble and upset the algorithms, history must be put back in its place. Technological determinism must again be made synonymous with historical determinism.•

Tags: Mark Zuckerberg, Nicholas Carr

In Carl Sagan’s 1969 article “Mr. X,” the physicist wrote of his marijuana experience, summing it up most colorfully this way: “When I closed my eyes, I was stunned to find that there was a movie going on the inside of my eyelids.” Dude!

A movie going on inside the head is one metaphor the Australian philosopher David Chalmers uses to try to describe that inscrutable thing called consciousness. He comes up with several other analogies in a Reddit AMA about the hard problem. Below are some of the more accessible exchanges.

Question:

In your TED talk you metaphorically characterized consciousness as “a movie playing inside your head,” and more comically in an IAI video as “that annoying thing between naps”. Do you have or have you come across any other metaphors of consciousness that you find fruitful when trying to get across just exactly what consciousness is?

David Chalmers:

um, the virtual reality inside our head? (probably better than a movie!) the thing mary wouldn’t know about from inside her black and white room, despite knowing all about the physical processes in the brain? the thing that makes us different from zombies or robots without an inner life? the first-person point of view?

Question:

When we talk about the dangers of AI, we may be talking about the danger of having a self-driven car and its decision making, or a more general AI and whether it will lead to an AI+, and ultimately to a larger danger concerning all of us. I am interested when philosophers (specifically) talk about the imminent dangers of the second type of AI, based on recent achievements (general Atari game playing, beating Go champion, usage in medical environments etc) and my question is: What do you think should be the relationship between academic philosophers, who focus on how imminent the AI danger is, and the actual engineering behind the aforementioned achievements? Should academic philosophers incorporate into their arguments what are the specific modelling techniques or search algorithms (eg monte carlo tree search, back-propagation, deep neural nets) and how they work when they argue about how close to the possible danger we are? If not, is the imminent part argued in a satisfactory way in your opinion?

David Chalmers:

i don’t know if philosophers are the best judges of just how imminent human-level AI or AI+ is. in my own work on the topic (e.g., the paper on the singularity) i’ve stressed that a lot of the philosophical issues are fairly independent of timeframe. of course it’s true that the question of imminence is highly relevant for practical purposes. i think that to assess it one has to pay close attention to the current state of AI as well as related fields: e.g. in the current situation, to try to figure out just what deep learning can and can’t do, what are the main obstacles, and what are the prospects for overcoming them. but the fact is that even experts in this area have widely varied views about the timeframe and are wary of making confident predictions. i chaired a panel on just this topic at the recent asilomar conference on beneficial AI, with eight leading AI researchers, and few of them were willing to make confident predictions (though consensus high-confidence area seems to be somewhere between 20 and 100 years). so i think that we should think about and plan for human-level AI in a way that is fairly robust over different timeframes.

Question:

Do you watch Westworld? It’s an amazing TV show that covers topics like AI and consciousness. If yes, what do you think about it?

David Chalmers:

i love westworld. it’s really well-done. i do think its reliance on julian jaynes’ long-discarded theory of consciousness (that it involves realizing the voices in your head are your own) is disappointing, though perhaps it’s somewhat cinematic. in general i think although the show presents itself as a meditation on consciousness in AIs and others, i think it’s much more of an exploration of free will. it seems to me that the AIs in the show are pretty obviously conscious, but there are real questions of what sort if any of free will they might have, given the way their actions are grounded in routines. and the “journey” of the AIs seems more like a journey toward free will and perhaps toward greater self-consciousness than toward consciousness per se. of course there are also very rich materials in the show for thinking about the ethics of AI.

Question:

Do you think any substantial progress on the hard problem of consciousness will be made in time for the debate on AI rights? If by that time we still haven’t made any progress on the hard problem of consciousness, how should humanity value the life of an “apparently sentient” AI, especially relative to a human life?

David Chalmers:

i hope so, but there are no guarantees. on the other hand, we can have an informed discussion about the distribution of consciousness even without solving the hard problem. we’re doing that currently in the case of consciousness in non-human animals, where most people (including me) agree that there is strong evidence of consciousness in many soecies. i think it’s conceivable we could get into a situation like that with AI, though there would no doubt be many hard cases. i do think that when an AI is “apparently sentient” based on behavior, we should adopt a principle of assuming it is conscious, unless there’s some very good reason not to. and if it’s conscious in the way that we are, i think prima facie its life should have value comparable to ours (though perhaps there will also be all sorts of differences that make a moral difference).

Question:

Do you think sustained consciousness will be worth it without the pleasures of the body?

David Chalmers:

i hope we don’t have to choose!•

Tags: David Chalmers

In the Digital Age, robots aren’t easy to identify.

That’s a problem since some, including Bill Gates, have recently suggested America tax them. On the face of it, that seems like a good idea, but the picture gets fuzzier the longer you stare at the situation.

Consider Uber, for instance. The company, using just algorithms, disrupted the taxi industry, undermining solid working-class jobs and replacing them with piecemeal precariousness, while employing very few workers in its own middleman function. Because it doesn’t utilize what we’d traditionally define as robots, it wouldn’t be taxable by the Gates standard. Even if we classify these computer systems as robotics and wanted to levy algorithm-centric companies like Uber–or Netflix or Amazon or Spotify–their effect on the economy, while real, is also amorphous.

Let’s say now that driverless becomes realistic within a decade. This capability would remove Uber’s freelance drivers from behind the wheel. Because autonomous cars are considered robotics, they could be taxed, which would create more resources for education and social-welfare programs. But in that scenario, couldn’t Uber just delay its transition until a more politically advantageous moment? That would be a lose-lose outcome from a purely economic viewpoint, since companies in other countries would likely move forward with this innovation and outstrip its U.S.-based counterpart.

Even with actual robots, it’s not so simple. For instance: Are Roombas taxed? We don’t know if they’re actually eliminating jobs or just toil. I don’t have any good answer in regards to this problem, but I don’t know that anyone else, Gates included, currently has one either.

In a smart Financial Times piece, philosopher Luciano Floridi cuts to the heart of the matter, arguing that seemingly easy answers to the situation just birth far more thorny questions. An excerpt:

We are laying down foundations for the mature information societies of the near future, so we need new ethical frameworks to determine which forms of artificial agency we are happy to see flourishing in them. Against this background, the EU’s initiative provokes mixed feelings: excitement at the aspiration but disappointment at the implementation. There is too much fantasy and too little realism.

Consider two key issues: jobs and responsibilities. Robots replace human workers. Retraining unemployed people was never easy, but it is more challenging now that technological disruption is spreading so rapidly, widely and unpredictably. There will be many new forms of employment in other corners of the infosphere — think of how many people have opened virtual shops on eBay. But new and different skills will be needed. More education and a universal basic income may mitigate the impact of robotics on the labour market.

Society will need more resources. Unfortunately, robots do not pay taxes. And more profitable companies are unlikely to pay enough extra taxes to compensate for the loss of revenues. So robots cause a higher demand for taxpayers’ money and a lower supply of it.

How can one get out of this tailspin? The report correctly identifies the problem. But its original recommendation of a robo tax on companies that employ robots — a proposal that did not survive into the final text approved the parliament — may not be feasible, for what counts as a robot? It may also work as a disincentive to innovation.•

Tags: Bill Gates, Luciano Floridi

Speaking of bigoted public businessmen, not even the Andrew “Dice” Jackson currently in the White House could hold a taillight to Henry Ford, who was such a virulent anti-Semite that he actually published a newspaper to disseminate his hateful views. The Model-T magnate purchased the Dearborn Independent in 1919, and until it was sued out of existence eight years later, he helped to fan the flames of intolerance that eventually led to the greatest tragedy of the twentieth century. At least, though, he never became President.

Retro racism isn’t the only aspect of Ford’s worldview that’s ascendant once more. Like today’s Libertarian sea-steaders and deep-pocketed New Zealand zealots, the industrialist dreamed of skirting rules and regulations and building a haven according to his narrow worldview far from the madding crowd. Fordlândia, as he modestly called it, was established in 1928 in the Amazon Rainforest to create a cheap supply of rubber for automobile parts.

It wasn’t long before the locals hired for the project bristled under the incredibly severe lifestyle requirements laid down by the plutocrat. Open revolt began. These uprisings and poor planning ultimately forced the settlement into failure by 1934, when it was abandoned.

From Simon Romero in the New York Times:

From the start, ineptitude and tragedy plagued the venture, meticulously documented in a book by the historian Greg Grandin that I read on the boat as it made its way up the Tapajós. Disdainful of experts who could have advised them on tropical agriculture, Ford’s men planted seeds of questionable value and let leaf blight ravage the plantation.

Despite such setbacks, Ford constructed an American-style town, which he wanted inhabited by Brazilians hewing to what he considered American values.

Employees moved into clapboard bungalows — designed, of course, in Michigan — some of which are still standing. Streetlamps illuminated concrete sidewalks. Portions of these footpaths persist in the town, near red fire hydrants, in the shadow of decaying dance halls and crumbling warehouses.

“It turns out Detroit isn’t the only place where Ford produced ruins,” said Guilherme Lisboa, 67, the owner of a small inn called the Pousada Americana.

Beyond producing rubber, Ford, an avowed teetotaler, anti-Semite and skeptic of the Jazz Age, clearly wanted life in the jungle to be more transformative. His American managers forbade consumption of alcohol, while promoting gardening, square dancing and readings of the poetry of Emerson and Longfellow.

Going even further in Ford’s quest for utopia, so-called sanitation squads operated across the outpost, killing stray dogs, draining puddles of water where malaria-transmitting mosquitoes could multiply and checking employees for venereal diseases.

“With a surety of purpose and incuriosity about the world that seems all too familiar, Ford deliberately rejected expert advice and set out to turn the Amazon into the Midwest of his imagination,” Mr. Grandin, the historian, wrote in his account of the town.

These days, the ruins of Fordlândia stand as testament to the folly of trying to bend the jungle to the will of man.•

Tags: Henry Ford, Simon Romero

Was planning on stopping by my favorite bookstore on Wednesday or Thursday to pick up a copy of Walter Scheidel’s The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Just as an extra nudge, the author published an article on the topic today in The Atlantic. As you might have guessed from the subtitle, it is not a hopeful piece. “With the rarest of exceptions, great reductions in inequality were only ever brought forth in sorrow,” the author writes.

No candidate was particularly honest about the economy and wealth inequality in the recent Presidential election. In one debate during the Democratic primary, Hillary Clinton argued that the free markets had allowed post-war America to create an upward trajectory for those seeking a solid middle-class existence. Well, not exactly.

The free market was important, sure, but it can’t be forgotten that progressive tax rates reached 90% during the Eisenhower Administration, a figure even your average liberal today would say is draconian, and that money was redistributed via investment in those who had less, often through education, social welfare and infrastructure development. Without flourishes from both capitalism and socialism, the level playing field that inched into the 1970s never would have existed for more than two decades. And if you remove World War II from the equation, it never would have happened at all.

Scheidel doesn’t relate his thoughts on the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era in this article, though hopefully he does in his book.

The opening:

Calls to make America great again hark back to a time when income inequality receded even as the economy boomed and the middle class expanded. Yet it is all too easy to forget just how deeply this newfound equality was rooted in the cataclysm of the world wars.

The pressures of total war became a uniquely powerful catalyst of equalizing reform, spurring unionization, extensions of voting rights, and the creation of the welfare state. During and after wartime, aggressive government intervention in the private sector and disruptions to capital holdings wiped out upper-class wealth and funneled resources to workers; even in countries that escaped physical devastation and crippling inflation, marginal tax rates surged upward. Concentrated for the most part between 1914 and 1945, this “Great Compression” (as economists call it) of inequality took several more decades to fully run its course across the developed world until the 1970s and 1980s, when it stalled and began to go into reverse.

This equalizing was a rare outcome in modern times but by no means unique over the long run of history. Inequality has been written into the DNA of civilization ever since humans first settled down to farm the land. Throughout history, only massive, violent shocks that upended the established order proved powerful enough to flatten disparities in income and wealth. They appeared in four different guises: mass-mobilization warfare, violent and transformative revolutions, state collapse, and catastrophic epidemics. Hundreds of millions perished in their wake, and by the time these crises had passed, the gap between rich and poor had shrunk.•

Tags: Walter Scheidel

The main reason I preferred Hillary Clinton to Bernie Sanders was simple math.

In addition to his impossible pledge of America no longer having the highest incarceration rate of Western nations by the end of his first term, Sanders based his extraordinary spending plans on fanciful economic growth numbers (5.3%) that he couldn’t possibly deliver. That promise made Sanders policies seem less debt-heavy than they were, a dishonest way of doing business.

Although Donald Trump is promising a smaller if still out-of-reach 3.0-3.5%, he’s doing something the Vermont Senator would have never done: Ordering the Council of Economic Advisers to backfill all of its projections at his unrealistic rate. That intellectually deceptive gaming, he hopes, will be the smoke and mirrors he needs to cover the exorbitant cost of the tax cuts he plans for the nation’s highest earners.

From Catherine Rampell at the Washington Post:

Astonishingly, the White House still hasn’t released details for any of the major economic initiatives Trump promised during the campaign (a “terrific” Obamacare replacement, a top-to-bottom tax overhaul, massive infrastructure investment). But thanks to recent leaks about the administration’s economic book-cooking, we at least know that whatever Trump ultimately proposes will be very, very expensive.

After the election, the Trump transition team began the long, arduous process of putting together the presidential budget. As is always the case, it worked with the (non-political) career staffers at the Council of Economic Advisers.

Normally this process starts by asking the CEA staff to estimate baseline economic growth under current policies. These professionals then build on this baseline to forecast how the president’s proposals will affect the overall economy, as well as budget deficits.

The end results are often more optimistic than what independent forecasters predict — the White House is factoring in new policies it believes are pro-growth, after all — but not wildly so. The numbers still need to be credible.

Like I said, that’s how things normally work. Not this time around.

As the Wall Street Journal first reported (and as I’ve independently confirmed through my own sources), the Trump transition team instead ordered CEA staffers to predict sustained economic growth of 3 to 3.5 percent. The staffers were then directed to backfill all the other numbers in their models to produce these growth rates.•

The robot threat is being taken to lightly

— Jose Canseco (@JoseCanseco) February 20, 2017

Robots will not attack and kill us physically like in the movies

— Jose Canseco (@JoseCanseco) February 20, 2017

For 60 years Robots have been systematically destroying us in clandestine economy based war started when eniac was turned on

— Jose Canseco (@JoseCanseco) February 20, 2017

Listen to ME all humans we need to wake the fuck up

— Jose Canseco (@JoseCanseco) February 20, 2017

Already today a fully robotized factory reduces human jobs 90% and increases production 250% and reduces defects 80% while doubling profit

— Jose Canseco (@JoseCanseco) February 20, 2017

Robots control every industry our food supply our transportation systems our health care and education systems EVERYTHING

— Jose Canseco (@JoseCanseco) February 20, 2017

robots are stealing our jobs bringing economic ruin to us human by human starving us to death one by one

— Jose Canseco (@JoseCanseco) February 20, 2017

All that will be left is uber technical humans trained to service robots.

— Jose Canseco (@JoseCanseco) February 20, 2017

Nothing pleases me more than the smart-stupid tweets from the account of Jose Canseco, which serves as its own parody. The former baseball player and amateur chemist has, it would seem, recently become aware of the Second Machine Age and has addressed its arrival in the most dystopian 140-character bursts possible.

In “No, Robots Aren’t Killing the American Dream,” the New York Times has a more sober Editorial Board take on the topic that gets a lot right, but it skates over some troubling points. The Times is correct in saying that robotics is good for a society’s wealth in the aggregate and that it should be a boon for all if robust public policy is done properly. But it makes that seem too simple.

“The response in previous eras was quite different,” the op-ed declares, suggesting yesteryear’s politicians were nimble with answers to the challenges that attended the Industrial Age. Not so. The rise of Labor Unions was born (quite literally) of blood, and the G.I. Bill, which the essay lauds, was labeled as “welfare” by those on the right who wanted to kill it.

The path to a fairer country was always a jagged one, and Times also fails to mention, perhaps most importantly, that the pace of change is poised to be far faster now as robotics matures, a dynamic that will put further stress on even good policy. Additionally, thinking of automation in a vacuum neglects an important part of the contemporary Labor story, as Internet companies with few employees have been able to disrupt industries formerly full of steady middle-class work. That’s another ingredient missing from the twentieth-century’s struggles.

Yes, policy is the answer. No, it never was so simple in our capitalist society and won’t be now.

An excerpt:

And yet, the data indicate that today’s fear of robots is outpacing the actual advance of robots. If automation were rapidly accelerating, labor productivity and capital investment would also be surging as fewer workers and more technology did the work. But labor productivity and capital investment have actually decelerated in the 2000s.

While breakthroughs could come at any time, the problem with automation isn’t robots; it’s politicians, who have failed for decades to support policies that let workers share the wealth from technology-led growth.

The response in previous eras was quite different.

When automation on the farm resulted in the mass migration of Americans from rural to urban areas in the early decades of the 20th century, agricultural states led the way in instituting universal public high school education to prepare for the future. At the dawn of the modern technological age at the end of World War II, the G.I. Bill turned a generation of veterans into college graduates.

When productivity led to vast profits in America’s auto industry, unions ensured that pay rose accordingly.

Corporate efforts to keep profits high by keeping pay low were countered by a robust federal minimum wage and time-and-a-half for overtime.

Fair taxation of corporations and the wealthy ensured the public a fair share of profits from companies enriched by government investments in science and technology.•

One troubling aspect of globalization is that those not adversely affected by the flow of international trade and actually helped by it (most Americans) are often opposed to a smaller world because of prejudice or some other irrational fear.

One troubling aspect of globalization is that those not adversely affected by the flow of international trade and actually helped by it (most Americans) are often opposed to a smaller world because of prejudice or some other irrational fear.

While financial concerns in the Rust Belt may have put Trump over the top (along with Russian hacking and FBI machinations), the bigoted President’s voters enjoy an overall higher household income than the average U.S. resident. Many were turning the lever for something else, and that was nationalism, which is sadly something most dear to many among us.

In an excellent Five Questions interview, Lawrence Summers discusses the strictly economic repercussions of globalization. He acknowledges that while he thinks the process still works in the big picture, our bumpy ride is just beginning, meaning we’ll need to strengthen “systems of social insurance,” something which seems to not be on the horizon in the U.S. Sooner or later, though, people will tire of bread and Kardashians.

An excerpt:

Question:

Finally, a title from last year. Richard Baldwin’s The Great Convergence (2016). Please give us a precis.

Lawrence Summers:

It’s the newest of the books and it’s a very powerful description of the newest phase of globalization. Two ideas about this newest phase of globalization that Baldwin emphasizes are hugely important.

The first is that we used to think very much in terms of trade in goods—some country exports washing machines, some other country exports dryers. Increasingly, goods are produced with global supply chains. Part of a good is produced in one country, part of a good is produced in another country and assembly takes place in a third country. So trade is part of the production process, whether it takes place within a multi-national corporation or between companies. Trade is part of production through supply chains.

The other idea that is emphasized is the role of trade and globalization in sharing knowledge. Baldwin uses a very powerful analogy. He says it’s one thing for a soccer team in one country to play against a soccer team in another country. It’s a very different thing if the coach in one country starts to coach teams in many countries and therefore promotes convergence. Baldwin argues that the second type of openness may be more problematic than the first. And, increasingly, trade is taking that form.

Question:

Please explain the challenges to politics and economic policy presented by this “great convergence” he describes.

Lawrence Summers:

The challenge is that there are likely to be more winners associated with global convergence, but there are also likely to be more losers and more potential volatility. In this latest stage of globalization, ideas can be traded and support production elsewhere, leading to less identification of entrepreneurship with location. The example I like to give is when George Eastman invented the instamatic camera, he got rich and Rochester, New York, where he founded his company, had a strong middle class for several generations. When Steve Jobs made equally powerful innovations, involving the iPhone and the iPad, the result was that he got very, very rich and there was an increase in the demand for labor globally, primarily in Asia, with no similarly broad increase in local wealth.

Question:

In recent years, you have been sounding an alarm about the role of globalization in contributing to local dislocations and inequality. What caused your worries and what are your solutions for globalization going forward.

Lawrence Summers:

I’ve said, for some years, that global integration won’t work if it means local disintegration. Unfortunately, that proved prescient.•

Tags: Lawrence Summers, Richard Baldwin

- The meek were promised they would inherit the earth, but policies change.

- Trump’s Administration, fueled by Exxon and coal, is eager to deregulate as many environmental protections as possible and embrace what will be the death of us. The willful ignorance of the ruling party may not kill off all of humanity–not immediately, anyway–but you better have a large bankroll or be especially lucky if you want a chance at persisting in life.

- I wrote last month on Evan Osnos’ New Yorker article about members of the financial elite planning on escaping a large-scale calamity, readying themselves for the Big Withdrawal from a disaster that will envelop their less-well-funded friends. Perhaps they’ll relocate away from the worst of a heating planet or maybe the wars that will likely attend higher mercury. Peter Thiel has a backup plan if the sociopath he enabled into the White House is the final nail in our coffin, but for most there will be no avoiding the creeping disaster of climate change.

- It’s the worst possible moment for the most destructive American political uprising in memory. The earth is cracked and so are the people.

In “The Slow Confiscation of Everything,” an excellent Baffler essay, Laurie Penny analyzes how the meaning of end-of-world scenarios have changed through the ages and the political undertones of the current ruinous impulses among the masses.

An excerpt:

This month, in a fascinating article for The New Yorker, Evan Osnos interviewed several multi-millionaires who are stockpiling weapons and building private bunkers in anticipation of what preppers glibly call “SHTF”—the moment when “Shit Hits The Fan.” Osnos observes that the reaction of Silicon Valley Svengalis, for example, is in stark contrast to previous generations of the super-rich, who saw it as a moral duty to give back to their community in order to stave off ignorance, want and social decline. Family names like Carnegie and Rockefeller are still associated with philanthropy in the arts and sciences. These people weren’t just giving out of the goodness of their hearts, but out of the sense that they too were stakeholders in the immediate future.

Cold War leaders came to the same conclusions in spite of themselves. The thing about Mutually Assured Destruction is that it is, well, mutual—like aid, or understanding, or masturbation. The idea is that the world explodes, or doesn’t, for everyone. How would the Cuban Missile Crisis have gone down, though, if the negotiating parties had known, with reasonable certainty, that they and their families would be out of reach of the fallout?

Today’s apocalypse will be unevenly distributed. It’s not the righteous who will be saved, but the rich—at least for a while. The irony is that the tradition of apocalyptic thinking—religious, revolutionary or both—has often involved the fantasy of the destruction of class and caste. For many millenarian thinkers—including the puritans in whose pinched shoes the United States is still sneaking about—the rapture to come would be a moment of revelation, where all human sin would be swept away. Money would no longer matter. Poor and privileged alike would be judged on the riches of their souls. That fantasy is extrapolated in almost every modern disaster movie—the intrepid survivors are permitted to negotiate a new-made world in which all that matters is their grit, their courage, and their moral fiber.

A great many modern political currents, especially the new right and the alt-right, are swept along by the fantasy of a great civilizational collapse which will wash away whichever injustice most bothers you, whether that be unfettered corporate influence, women getting above themselves, or both—any and every humiliation heaped on the otherwise empty tables of men who had expected more from their lives, economic humiliations that are served up and spat back out as racism, sexism, and bigotry. For these men, the end of the world sounds like a pretty good deal. More and more, it is only by imagining the end of the world that we can imagine the end of capitalism in its current form. This remains true even when it is patently obvious that civilizational collapse might only be survivable by the elite.•

Tags: Laurie Penny

Tried to imagine a President worse than Trump and all I could come up with was someone identical to him but competent and disciplined. Imagine that?

The new President and putative Putin puppet held a campaign rally this weekend, just four weeks after being inaugurated, because he never wanted to be President–he just wanted to run for the position. The trail is where the applause and consequence-less boasts are, while the Oval Office is the location of the hard work that never ceases. Of course, his inability to focus on the job, while it may impede some of his worst policy, can also get lots of people killed, right now and in the future.

This horrid time, however long it should last, will have all sorts of repercussions for tomorrow, especially since our foreign policy now is an ad hoc collection of ever-changing postures and trade wars, which will reduce the efficacy of our soft power even if we retain our military might. Additionally: Lots of people can get blown up.

Two excerpts below about the vacuum which now exists on the world stage where American doctrine formerly resided.

From Eliot A. Cohen’s Atlantic piece “The Rudderless Ship of State“:

There are two theories of the future of President Trump’s foreign policy and the National Security Council. In one, the good ship NSC, like a Nantucket whaler of old, has had a hard shakedown cruise, but is coming to. A couple of misfits have been tossed overboard, and the captain has given up trying to run the ship. He periodically shows up on deck to shake his fist at the moon and order a summary flogging, but for the most part he stays in his cabin emitting strange barks while competent mates and petty officers sail the NSC. It’s not pretty—the ship rolls and lurches alarmingly—but it gets where it needs to go.

This could happen. Trump, overwhelmed by a leadership task far beyond his experience and personality, will focus his efforts on infrastructure projects and the like, and quietly concede the direction of foreign policy to his sober secretaries of state and defense, with a retired general or admiral to reassemble something like an orderly White House process. He is erratic but not stupid: he knows he is in over his head, hates the bad publicity his first few weeks bought him, and has family members nudging him in this direction.

Unfortunately, another possibility is more likely: The ship is in serious trouble. The first reason is that the system cannot function with an absent commander in chief. Since World War II, the United States has evolved a system for making foreign policy that depends on an effective White House operation in the form of the National Security Council staff. (The NSC itself consists of Cabinet secretaries and the like, not aides and bureaucrats.) The elaborate hierarchy of interagency committees that evolved actually works rather well most of the time, but it depends critically on the ability of a competent staff working directly for the president to orchestrate it.•

From Jon Finer’s Politico article “Trump Has No Foreign Policy“:

What is different is that right now not only is there no discernible doctrine guiding President Donald Trump’s foreign policy, the United States currently has no real foreign policy at all. By that I mean not that the policies are objectionable, or that the Trump team is struggling with the learning curve each new administration faces at the outset, as it reviews its predecessors’ approach and settles on its own. Rather, I mean that we are experiencing an unprecedented degree of policy incoherence on virtually every major issue the country faces.

And so it was left to Vice President Mike Pence on Saturday to travel to the Munich Security Conference, the most important annual gathering of politicians and national security wonks, to reassure America’s increasingly nervous European partners that things in Washington are under control. The meetings can be insufferable, but they are also an important chance, especially at the start of an administration, to help the world understand what policies it will pursue.

Pence did perfectly well, in what must have felt like Mission Impossible. He told America’s allies what they wanted—actually, needed—to hear: that the United States would continue to “hold Russia accountable” for its aggression in Ukraine, that we remained deeply committed to the NATO alliance, that the values underpinning transatlantic relations remain sacrosanct.

The problem is, no one really knows if Pence speaks for the administration on foreign policy—or, for that matter, if anyone does. Policy is, at its core, a function of what the government does and what it says. While it is too soon for the Trump administration to have done much, what is being said is either nothing or completely contradictory things. Pence’s message about shared values was undercut both before and minutes after his remarks by President Trump, with his latest tweets attacking the mainstream media as “fake news” and, more outrageously, “the enemy of the American people.”

There are many more such examples of incoherence.•

Tags: Eliot A. Cohen, Jon Finer

Newspapers could simply fade in America, unable to make the post-print transition, but what if they’re able to turn a profit from a much smaller readership and sustain themselves, even thrive, in that fashion?

If companies can monetize this tinier base without touching the masses, that could lead to the present polarization becoming permanently entrenched, a battle between those largely informed and those not nearly. You don’t have to ban books if most people aren’t reading, and you needn’t censor the news if enough eyes are closed.

On his blog, journalist Clive Davis posted a pertinent quote from Alistair Cooke, who wondered in 1952 how fascism would be received when newsprint was no longer prominent, when a Hitler wouldn’t even have to bother to wrest control of the presses. An excerpt:

We don’t know yet what the televising of the conventions will do to American politics, to elections, to the convention system itself. Some of us fear what one good demagogue with a fine voice and a rousing profile might do to the tyranny of popular government…. The only time that I ever saw Adolf Hitler was at a big rally outside the Brauhaus in Munich in 1931. I was a student who had only just heard of him. I got jammed in there and I watched him and soon felt my heart begin to pound. He was – all morals, politics aside – a superb performer. When he got to his peroration, he ended on a practically meaningless sentence. He shouted, “It is five minutes to twelve.” Nobody knew in his head what Hitler meant. But they felt they had been slapped on the back and a sword put in their hands. Hitler paid a direct physical compliment to the nervous system. I had to fight my frightened way out over fainting women and cheering, sobbing men.

I was glad the next morning to sit down and see it in the newspaper and know that most Germans could sit back and read, and judge the speech unmoved, unseduced by the physical experience of the thing itself. The next Hitler will not suffer from this restraint.•

Tags: Alistair Cooke

10 search-engine keyphrases bringing traffic to Afflictor this week:

- henry kissinger donald trump

- donald rumsfeld donald trump

- you won’t like what comes next after america

- ta-nehisi coates playboy interview

- certainly we are at peak dystopia

- don lemon gq profile

- brexit and its aftermath

- vladimir nabokov u.s. road trip

- virtual reality empathy machine

- first american killed in auto accident

This week, Florida car salesman Gene Huber told CNN he salutes a life-size cutout of Donald Trump every day.

- Intel leaks may be the best bet to prevent the end of American democracy, but an enduring “Deep State” could emerge.

- Yale historian Timothy Snyder talks Trump’s dictatorial threat.

- Garry Kasparov advises on how to prevent American autocracy.

- Jared Kushner isn’t a mitigating force but an enabler of Breitbart bigotry.

- Elon Musk, a Trump patsy, discusses cyborgism and Basic Income.

- Bradley Tusk has deeply amoral advice for Silicon Valley in the Trump Era.

- Trump’s myopia on terrorism may have dangerous consequences.

- Trump chair Steve Schwarzman’s birthday party featured acrobats and camels.

- America’s future shouldn’t be manufacturing but instead the “caring industry.”

- The Philippines is under the perilous sway of demagogue Rodrigo Duterte.

- Bad medicine and bad journalism fueled needless fears about vaccines.

-

The UAE announced it intends to build the first Martian city by 2117.

- Old Print Article: Russia or robots may ruin America. (1950)

- Two brief notes from 1938 about a love potion.

- This week’s Afflictor keyphrase searches: Trump’s Russian business deals, etc.

“You’re far better off affecting policy if you’re in the room” is a true statement in U.S. politics if we’re talking about your average conservative, liberal or moderate elected official, but it doesn’t extend to this moment in our history, with a reckless, dangerous, kleptocratic and, perhaps, traitorous sociopath in the White House.

In this case, it’s better to be outside the room, refusing to lend your reputation to an aspiring autocrat and raising your voice in protest, especially if you have a giant megaphone like Travis Kalanick or Elon Musk. The former did the morally correct thing in resigning from Trump’s economic advisory council, while the latter still sees this un-American Administration as a game he can officiate.

In a jaw-dropping BuzzFeed article, William Alden reports on political consultant Bradley Tusk’s work advising Silicon Valley titans on how to deal with a deeply irregular White House, encouraging them to ignore their consciences at all costs and do what’s best for the bottom line. It’s not shocking there are people so amoral they can’t see beyond business as usual even in these desperate times, but it is surprising to hear someone so publicly announce such a dicey position.

An excerpt:

Last week, he sent a memo to clients outlining a strategy for dealing with Trump, advising them to take a deep breath and think before engaging in political protest. Taking a stand against Trump might be the right choice, Tusk said, but only if it makes business sense.

“If the business demands immediate action, that’s one thing. If it’s your conscience, that’s another,” he wrote in the memo. Pressure from the media or even from employees, he added, wouldn’t necessarily be a sufficient reason to speak out, especially if it would create other problems.

The memo came just days after Tusk’s flagship client, Uber CEO Travis Kalanick, resigned from President Trump’s economic advisory council. More than 200,000 Uber customers had deleted their accounts, according to The New York Times, after the ride-hailing company was accused of trying to undermine a taxi strike over Trump’s immigration order. Uber also came under pressure from employees and drivers, many of whom are immigrants. Kalanick’s resignation from the advisory council contrasted with the decision of another tech titan, Elon Musk, to stay there.

“This is one of those cases where the symbolism and the emotion on both sides of it took everything in such an incredible direction that people like Travis, like Elon, who are pretty well intentioned, and are saying, ‘O.K., let’s see if we can help things,’ got put in a really, really impossible position,” Tusk told BuzzFeed News. “And they’re handling it in different ways. But that’s kind of why I wrote this memo.”

Tusk said Kalanick made the right decision in this case, but he expressed regret that it had to be that way. “I think Travis joined the council for the right reasons,” Tusk said. “You’re far better off affecting policy if you’re in the room.”•

Tags: Bradley Tusk, Elon Musk, Travis Kalanick, William Alden

Another repercussion of having a Constitution-shredding sociopath in the Oval Office is the possibility that a foundation will be laid for a long-term bifurcated government, with the executive branch and the intelligence community constantly angling to undermine one another.

The concern of a “Deep State” in Washington or worries of the White House operating a shadow National Security Agency speak to the fathomless rift orchestrated by a deeply polarizing President. Intel leaks about the Administration’s involvement in Russia have become a deluge, spies are reportedly withholding information from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue for fear they’ll be shared with the Kremlin and Trump has threatened a review of the intelligence community to be spearheaded by one of his billionaire buddies.

Agents anonymously leaking the truth may be the best bet to prevent the end of American democracy, but in the long term (should there be one) the intelligence community being put in a position where it has to go rogue could have serious ramifications. As Karl Rove said: Elections have consequences.

From “As Leaks Multiply, Fears of a ‘Deep State’ in America,” by Amanda Taub and Max Fisher of the New York Times:

Though the deep state is sometimes discussed as a shadowy conspiracy, it helps to think of it instead as a political conflict between a nation’s leader and its governing institutions.

That can be deeply destabilizing, leading both sides to wield state powers like the security services or courts against one another, corrupting those institutions in the process.

In Egypt, for instance, the military and security services actively undermined Mohamed Morsi, the country’s democratically elected Islamist president, contributing to the upheaval that culminated in his ouster in a 2013 coup.

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has battled the deep state by consolidating power for himself and, after a failed coup attempt last year, conducting vast purges.

Though American democracy is resilient enough to resist such clashes, early hints of a conflict can be tricky to spot because some push and pull between a president and his or her agencies is normal.

In 2009, for instance, military officials used leaks to pressure the White House over what it saw as the minimal number of troops necessary to send to Afghanistan.

Leaks can also be an emergency brake on policies that officials believe could be ill-advised or unlawful, such as George W. Bush-era programs on warrantless wiretapping and the Abu Ghraib detention facility in Iraq.

“You want these people to be fighting like cats and dogs over what the best policy is, airing their views, making their case and then, when it’s over, accepting the decision and implementing it,” said Elizabeth N. Saunders, a George Washington University political scientist. “That’s the way it’s supposed to work.”

“Leaking is not new,” she said, “but this level of leaking is pretty unprecedented.”•

Tags: Amanda Taub, Donald Trump, Max Fisher