If your reflexive response to the Grenfell Tower Fire tragedy, expressed even before all the charred bodies have all been recovered and identified, is to pen an essay-form cost-benefit analysis of the sprinkler system that the British government didn’t force the public-housing builder to install, you probably will be inundated with criticism online. You should be.

Megan McCardle did just that in Bloomberg View earlier this year in a column that ran with the subheading: “Perhaps safety rules could have saved some residents. But at what cost to others’ lives?” It’s unlikely the essayist herself came up with that line, but the editor who did perfectly captured the gist of the piece. It’s one of the more stunning examples of McCardle’s Libertarian delusions, in which the invisible hand of the free market will magically guide us to the correct decisions, something proven to be utter bullshit from the Shirtwaist Triangle Fire to Grenfell and many terrible moments in between.

An excerpt:

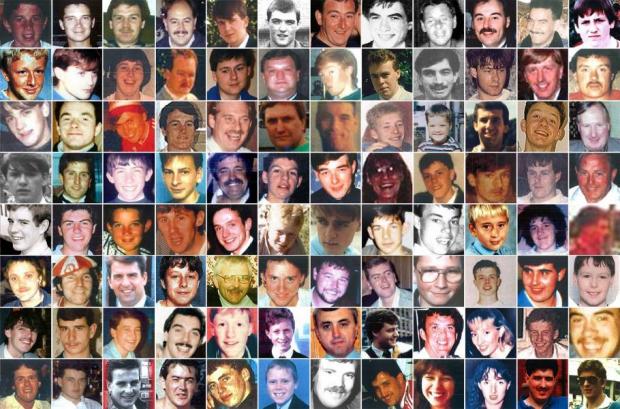

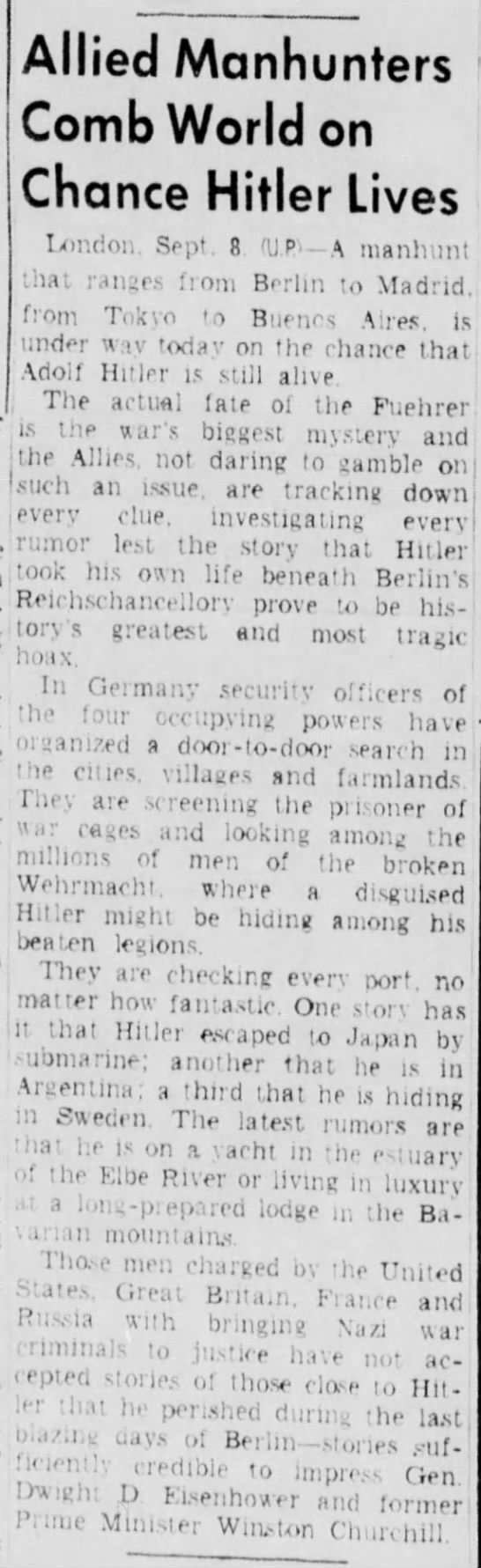

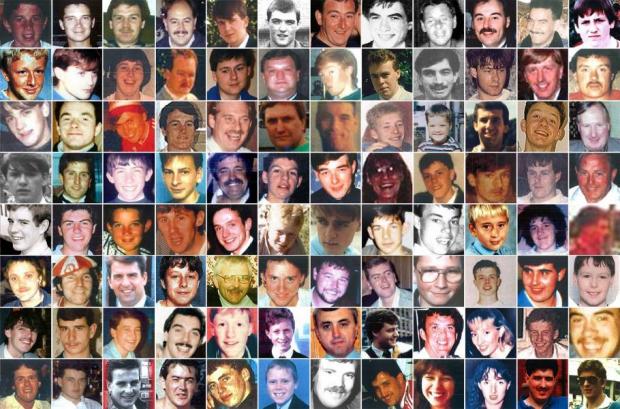

A few days ago fire swept through Grenfell Tower, a large apartment building in London. It’s not yet known what caused the fire, and we aren’t conclusively sure how it spread so quickly, consuming the entire 24-story building. Nor is it known how many died in the fire; as of Friday, the count is at least 30.

What we do know is that there are ways to help control the spread of fire in apartment buildings, such as sprinkler systems. This has the makings of a scandal for Prime Minister Theresa May’s beleaguered government. Her immigration minister, Brandon Lewis, was formerly the housing minister. He declined to require developers to install sprinklers. The Independent quotes him as telling Parliament in 2014: “We believe that it is the responsibility of the fire industry, rather than the Government, to market fire sprinkler systems effectively and to encourage their wider installation. … The cost of fitting a fire sprinkler system may affect house building — something we want to encourage — so we must wait to see what impact that regulation has.”

People who died in the Grenfell fire might be alive today if regulators had required sprinkler systems. This does not play well for the Tories.

But before we start hanging them in effigy, there are a couple of things we should consider. The first is that, even if the regulation had passed, and required existing developers to retrofit sprinklers into older buildings, Grenfell Tower might not have gotten a sprinkler system before the fire occurred. Regulations are not implemented like instant coffee; they take time to formulate, and further time for businesses to comply. All the political will in the world cannot conjure up enough sprinkler systems, and sprinkler-system installers, to instantly transform a nation’s housing stock.

This, however, is only a quibble; even if Grenfell Tower could not have been saved, there are surely other buildings where fires will soon occur that would benefit from sprinklers. Must we wait for those deaths before we can say that his was a bad calculation?

Well, no. But we should wait until we can establish that it was actually a bad calculation.

It may sound heartless to discuss life-saving measures as a calculation. But the fact is that we all make these sorts of calculations every day, about ourselves and others. We just don’t like to admit that we’re doing it. …

Back to the case at hand: Maybe sprinkler systems should be required in multifamily dwellings. It’s completely possible that the former housing minister made the wrong call. But his comment indicates he was thinking about the question in the right way — taking seriously the fact that safety regulations come at a cost, which may exceed their benefit. Such calculations have to be made, no matter how horrified the tut-tutting after the fact.

And he is certainly right about one thing: When it comes to many regulations, it is best to leave such calculations of benefit and cost to the market, rather than the government. People can make their own assessments of the risks, and the price they’re willing to pay to allay them, rather than substituting the judgment of some politician or bureaucrat who will not receive the benefit or pay the cost.

Grenfell Tower, of course, was public housing, which changes the calculation somewhat. And yet, even there, trade-offs have to be made.•

In a recent EconTalk podcast, Russ Roberts, a scholar at the Mercatus Center, a think tank funded by the regulation-loathing Koch brothers, discussed “Internet shaming and online mobs” with McCardle, who still doesn’t seem to get the effect her polite essays in legitimate publications can have on the lives of others. She’s certainly correct that nobody should be harassing others online or off with death threats over ideas, even ugly ones, but she comes across far more concerned about the standing of those who try to oppress others than the oppressed ones fighting back. Case in point: She’s worried about the earning power of amateur biologist and former Googler James Damore more than the women he dismissively and falsely depicted. Perhaps the free hand of the market gave him just the slap he needed?

An excerpt:

Russ Roberts:

Before we go on, I want to challenge one thing at the root of your concerns; and then I want to talk about some of what I think we can do about it. And then you can suggest whether you agree or what your own ideas are. But, the thing I want to raise is: Some would argue, perhaps legitimately–I don’t agree, but I’m not sure how I feel about this, actually–that shaming is good. That, all of this stuff that you are worried about–yes, people are scared about what they say: Well, they should be scared, goes this argument. Because, words can hurt people. Words are important. And, it’s a glorious thing that we have made people sensitized about the harmful effects of their words. And, the things that you are decrying, Megan, are actually good. One extreme version of this would be–and this drives me crazy, but I’ll put it forward anyway: ‘Well, if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing–if you don’t say anything bad–there’s nothing–you are not going to get hurt.’ All this shaming is to punish people who tell disgusting jokes, write grotesque memos that say things at the water cooler that intimidate and harm people. And those people should be shamed.

Megan McArdle:

So, I think that that is actually true up to a point. I’ve made this point before. In fact, the first column I ever wrote on online shaming, which was based on Jon Ronson’s excellent book on the topic, in which I coined the term “shame-storming,” which sadly failed to catch on, denying—

Russ Roberts:

I’m surprised. It’s a great name—

Megan McArdle:

Yeah. Somehow, I try to coin these things periodically, as all writers do. And mine never catch on. Julian Sanchez, on the other hand, like, just tosses them offhand and they are always amazing, you know, apt and meaty. But, yeah. Look. When people tell racist jokes, and their friends turn around and say, “That’s not funny and you shouldn’t say that,” right? That’s useful. Completely useful.

Russ Roberts:

It’s how society evolves. Those are the norms–

Megan McArdle:

How society has to happen. There is no society–

Russ Roberts:

Those are the Smithian norms of judgment. And people’s desire to be lovely, and to be respected by their friends. And it constrains behavior. It is great.

Megan McArdle:

There is no society that gets along without that. That’s not what we’re doing at this point, though. Right? We’re not just–look, I have been on the Internet 15 years. I have said some things I should not have said, and gotten people screeching at me. Justifiably. And then sometimes not justifiably. I have had pictures of my house even mailed to me with a gun-sight over the house. I have had death threats. I have had all this stuff. You shouldn’t send death threats to people; you should not make even photographic even kind of pseudo-death threats. But I get—”I hope you and your family die”; “I hope etc., etc.” I get that all the time. And, some of it is productive. Some of it is not. But, that’s all, to me, kind of all in the game. And it’s terrible—I feel terrible for this, that girl at Yale who got filmed saying some really intemperate and unwise things to her professor–screaming profanity at her professor–

Russ Roberts:

In a moment of emotion—

Megan McArdle:

In a moment when–she should not have screamed profanity at her professor; I will say that. But I will also say that the Internet definitely should not have deluged her with horrible, ugly messages. Right? And I’ve been through it; and I know, like, the first 10 or 20 times it happens to you it’s really terrible. Now, it just rolls off my back. I can’t even—

Russ Roberts:

That’s because that comes with the territory. And it shouldn’t come with being an 18-year-old in college as a freshman, or a junior, or a senior and having to deal with it out of the blue, unexpectedly. It’s not right.

Megan McArdle:

But, it’s also a different thing. However terrible it is, you move on. You kind of huddle for a few days. You feel bad; you tell all your friends how bad you feel. And then, a year later–yeah, it was bad, but you’ve gotten over it. Right? The difference now is–there’s a couple of things. One of them has to go to that tweet that you talked about–the global warming tweet. It’s like a year old. And periodically it just comes back to life. And how it comes back to life? Someone finds it; someone retweets it; there’s a whole new level of people screaming at you. And again, for me, this is my job. It’s all in the game. You want to scream at me, go right ahead. But, that happens to these people who get Internet shamed. But, more than that, there’s a lot of economic consequences here. You look at someone like Memories Pizza, the pizza place in Indiana that told people they wouldn’t do, cater gay weddings. Like, what are the odds that a pizza place in a small town in Indiana was actually ever going to be asked to cater gay weddings? But, the Internet went crazy. And these people were just deluged with horrible messages. The ultimately had to close down. Then they got a lot of donations. So, there’s two camps; and there can be counter-benefits as well. But, when you are talking about depriving someone of their livelihood–and this goes back to Brezhnev, right? If someone told the Brezhnev joke and all of your friends said, “That’s not funny, and you should not question our fearless leader,” you know, that would be creepy. Maybe you would want to get new friends. But, it would be within the kind of bounds of normal, human, social reaction. The problem is when you are actually afraid they are going to take away the means by which I make my living. That is an enormous amount of power. And that is ultimately what I ended up talking about in this article–is that, classical liberals, and libertarians, of which I think you and I are both one–we normally have two categories: Private power, which is fine, because it’s bounded; because there’s exit. And then there’s Public power, which has guns behind it, and it’s not bounded; and is a different animal; and that’s the animal that we focus on. Right? And there can be some cases of companies that kind of get so much monopoly power that they start acting like governments. But it’s actually pretty rare. This is a third creature, that seems to be in between those two things. Right? Because it’s not one company. Someone Google–this guy just got fired from Google. Well, you go work for another company that’s–maybe doesn’t care so much. Where you haven’t made your co-workers angry, or whatever. All companies are probably going to be afraid to hire this guy.

Russ Roberts:

I think small companies might take a chance on it, if his skills are such.

Megan McArdle:

Sure, but he’s never going to get a–

Russ Roberts:

He’s damaged—

Megan McArdle:

He’s damaged. In a way that was not true 10 years ago when it was just, you said something bad on the Internet and then people screamed at you and felt bad. And sometimes you said, “Yes, I shouldn’t have said that.” And sometimes you earned it back. But either way, it was bounded. When you threaten someone’s economic livelihood, you are threatening pretty close to killing them. Right? If you can’t make money to survive, then–it’s not the same as threatening to kill them, but it’s probably the next worst thing a government can do, is after bodily harm and threat or death, what can the state threaten you with? They can take away all of your money. They can take, freeze your bank accounts. They can make it impossible for you to live in society. And that is a thing that this power is starting to approach. And when we talking about freezing accounts, a Southern Poverty Law Center designated a small, kind of religious values institute–they are quite conservative; the head of the institute seems to be Catholic and quite traditional Catholic. They were rated a hate group and their payment provider cut them off. So, they couldn’t take donations. Those kinds of powers, when they are ubiquitous–when it isn’t just, this happens and then like it was just, you know, “My bank didn’t want to deal with me because of my views, so I went and got another bank.” Right? That is a fundamentally different thing from ‘Now, all the banks don’t want to touch me.”•