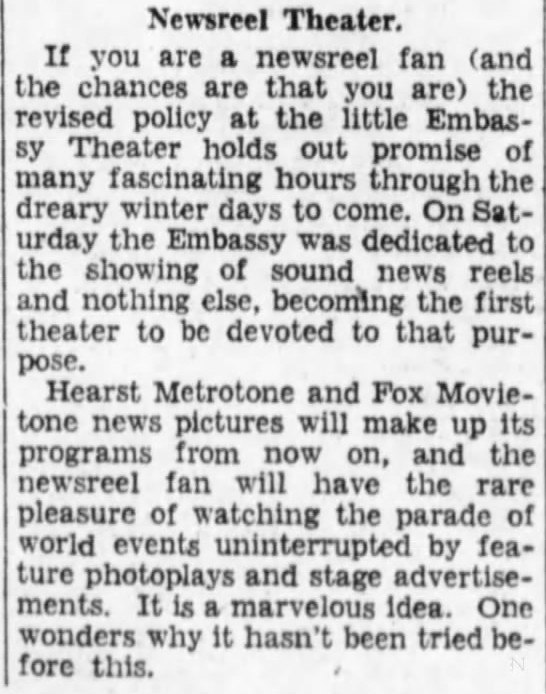

The “Fox” in Fox News is taken from the surname of pioneering film producer William Fox, whether he would be happy with the contemporary association or not. One of Fox’s great innovations was the launching, in 1929, of the Embassy Newsreel Theatre in Manhattan, as a showcase of continuous non-fiction fare, presaging around-the-clock cable by many decades. Newsreels–or “film newspapers“–had been popular since the beginning of cinema, but until Fox they were secondary to the main attraction in the United States. He redefined them as the attraction. By 1930, the proprietor had lost control of his film company and theaters, having been knocked out by a near-fatal automobile crash and the stock-market collapse. This reversal was followed by legal problems, a commission of perjury and a prison stint. Fox died in 1952, largely forgotten by the media he helped define. The text of a brief, understated article from the November 4, 1929 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, unwittingly announcing the moment when news in America–or something resembling it–became an infinite loop:

Tags: William Fox

We’ve shrunk the world, and now it’s portable and harder to see. That’s good and bad. To paraphrase Norma Desmond, is it just the pictures that have gotten smaller, or is some part of us also diminished? In the macro, it’s a huge victory, but there are losses even in the greatest gains. From Neil Gough at the New York Times:

“For the first time, more Chinese people are gaining access to the Internet with mobile devices than with personal computers.

The shift is significant, if expected, in China, which is the world’s biggest market for both Internet and smartphone users.

China had 632 million Internet users at the end of June, an increase of 14.4 million since the end of December, according to a semiannual report published on Monday by the official China Internet Network Information Center, which is known as CNNIC. Of those, 83.4 percent reported gaining access to the Internet with mobile devices, exceeding for the first time the percentage who reported using computers to go online, at 80.9 percent.

The results of the survey showed that more Chinese were heading online to send instant messages (through popular mobile apps like Tencent’s Weixin, or WeChat), listen to music, play video games and read.”

Go here to listen to a really good Econtalk discussion between economists Russ Roberts and Mike Munger about the sharing economy. Uber and Airbnb certainly provide improved offerings (though not always a lower price), but they also skirt tax and regulatory rules. It’s pretty clear that consumers want a peer-to-peer economy, but there are consequences for those who’ve adhered to traditional regulations. What if you spent a million dollars on a NYC taxi medallion a few years ago only to find out the value of your purchase has cratered (which hasn’t happened yet but potentially could) because of Uber and Lyft and the like? These companies have improved the transportation market, they’ve innovated ways for consumers to connect to cabs, but they aren’t playing by the rules.

So here’s the question: What happens to all parties when the rules have changed in practice but not (yet) on paper? Munger thinks New York will ban Uber, but it’s hard to believe those market forces will be constrained for very long. Nor should they be, really. One passage from the discussion:

“Russ Roberts:

We should explain. A medallion is–

Mike Munger:

A license.

Russ Roberts:

It’s a license that allows you to, in the case of a cab company, to pick up a stranger on the street who is raising his hand, saying, ‘Taxi’. There has always been an out for limos. You can always call a limo service to your house. I don’t think they need the same–they don’t have the exact same regulatory structure. But certainly, it is against the law in almost every city in America to cruise around and offer to pick up somebody who is raising his or her hand looking for a taxi and act like a taxi. And what Uber has done is be a little bit different. Sort of like that, but a little bit different. And that’s what the regulatory issue is.

Mike Munger:

Yeah. It’s much harder for the police. You don’t have to raise your hand, now. You just press a button on your phone unobtrusively. And the police don’t know. For all they know, it’s your friend picking you up at the airport.

Russ Roberts:

But, I think you exaggerate slightly. So, the medallion–now medallions have sold recently for as much as a million dollars.

Mike Munger:

In New York.

Russ Roberts:

In New York. Despite the Chicago story. So, there are people who are still investing in the right to be a taxi cab driver, either because they think that Uber is not as important as we do, or they think that Uber will be stopped and shut down and will not be a competitive force.

Mike Munger:

I predict that Uber will be stopped and shut down.

Russ Roberts:

Okay, I’m going to go against you there. I’m going to disagree with you. It is under tremendous regulatory pressure. Pittsburgh just announced–

Mike Munger:

I just meant in New York. In New York City. I just think that the people who made that, are making a good bet. It’s too easy to make a sting operation.

Russ Roberts:

Okay. We’ll see. But I do think that–the question isn’t that–I don’t think that Uber is illegal right now. It’s a gray area. Pittsburgh has just ruled that it must comply with the Pittsburgh Utility Council’s, or Pennsylvania Utility Council’s regulations. In Europe there’s tremendous pressure to shut down Uber, not allow them. But remember, there is tremendous pressure from riders. Who like it. And I think–I want to make sure we make something clear here. There are two aspects to this attractiveness of Uber. One of them–I don’t think it’s so much the price. I don’t think the price is that much different. I think it’s the convenience and power of it, on a calm, normal day; and I think it’s its ability change price on the fly, using a fairly sophisticated algorithm.

Mike Munger:

But the taxi companies can mimic all of that. They’ll do it within a month. It’s easy to do. If that were the reason, that’s easy to do. It’s basically open-source software.

Russ Roberts:

I don’t know about that. Um, you are suggesting then that the cab company doesn’t offer me a web, a phone-based opportunity to hail a cab because they don’t need to? Because they have a monopoly?

Mike Munger:

Yeah.

Russ Roberts:

I don’t know. I think the software is what gives Uber its comparative advantage.

Mike Munger:

It’s interesting that the taxi companies are so awful at this. So, if nothing else, Uber may force the taxi companies to improve the way that you connect with a taxi. But I think the cost advantage is really a problem, because it actually raises a lot of questions about the nature of due process. Suppose that we don’t take any action and the value of these medallions falls to zero. Are we obliged to offer compensation, because we in effect made a regulatory decision that is a taking? This property right, this medallion, had significant value. We made a choice, without due process, that said we are going to reduce the value of this medallion to zero. Are we obliged to compensate?

Russ Roberts:

Who is ‘we’?

Mike Munger:

The state. Just like we would if we were taking your land under eminent domain to build a road.”

Tags: Mike Munger, Russ Roberts

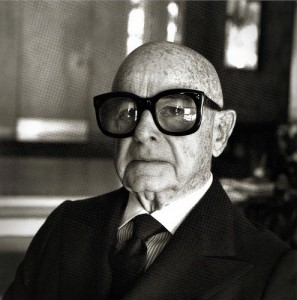

Irving “Swifty” Lazar, whose entire head was made of bifocals, was a lawyer who learned you could make a killing as an agent if you held fast to situational ethics. From Harry Minetree’s 1975 People article about Lazar, as he had just closed a book deal for a disgraced Richard Nixon and had agreed to let the former President sit for an interview with David Frost:

On a bright morning last August, Irving Paul (Swifty) Lazar, the literary agent, was having breakfast beside the pool at his Beverly Hills home when the telephone interrupted. It was Ron Ziegler, ex-President Nixon’s ex-press secretary, calling from San Clemente. Mr. Nixon, Ziegler said, was eager to see Lazar to discuss “some business.” Lazar, who had a pretty good idea what the business was, crisply replied that he was leaving for Europe shortly, but he would be happy to see Mr. Nixon upon his return.

On August 31 the dapper, billiard-bald Lazar and Nixon met over a three-hour lunch at San Clemente. Afterward, agent Lazar returned home in his black limousine with the exclusive rights to sell the former President’s memoirs in his attaché case. No matter that Swifty, a lifelong Democrat, had been an indefatigable fund-raiser for John F. Kennedy. Or that his Washington representative, Ann Buchwald, the wife of political satirist Art Buchwald, quit as a result of the Nixon deal. There was a buck to be made, in fact millions of bucks and, true to the 10-percenters’ code, Lazar had a flexible philosophy to suit the occasion: “In a deal you give and take. You compromise. Then you grab the cash and catch the next train out of town.”

Not many literary agents can afford to be so candid about their modus operandi. But then not many of them can afford a California mansion with genuine Picassos, Roualts, Chagalls and Dalis on the walls, a Rolls-Royce and a Mercedes in the garage, an elegant pied-a-terre in New York, offices in Beverly Hills, New York, London, Paris and Rome, $40,000-a-year phone bills and a custom-made wardrobe. There is only one “Swifty”—a soubriquet Humphrey Bogart laid on him after Lazar acquired three hot screen properties for him in the space of 24 hours—and indeed there is hardly room for more than one Swifty in the agents’ trade.

With characteristic speed, Lazar put together a package for Nixon: he sold the paperback rights to the book, which will probably appear in three volumes, to Warner Paperback Library for $2.5 million, the television rights for a Nixon interview to David Frost for another $750,000 and is asking for a hard-cover advance in the neighborhood of $1 million. (Although Lazar says Nixon was persuaded to accept Frost’s proposition because of the “interesting approach,” the word around Hollywood is that the interesting approach was simply the highest bid.) Still to be negotiated are foreign rights, book clubs, a possible movie and other spin-offs that will propel the former President back into millionaire status and guarantee Swifty Lazar fees well in the area of half a million. Even so, Lazar went through considerable soul-searching before he decided to represent Nixon. “He asked the advice of everyone he knows,” says Art Buchwald. “But it’s probably for the best. When a politician gets in trouble he deserves the best lawyer and the best literary agent around. You use the agent to pay the lawyer—that’s the way it goes.”

Nixon represents only the latest in Lazar’s ledger of famous, infamous, literary, political and showbiz clients. Over the years, he has represented Hemingway, Ira Gershwin, Truman Capote, Clifford Odets, Vladimir Nabokov, Neil Simon, Herman Wouk, Lerner and Lowe, John Huston, Edna Ferber, Buchwald, Noël Coward and Richard Rodgers, among others.•

Tags: Ann Buchwald, Art Buchwald, Harry Minetree, Irving "Swifty" Lazar, Ron Ziegler

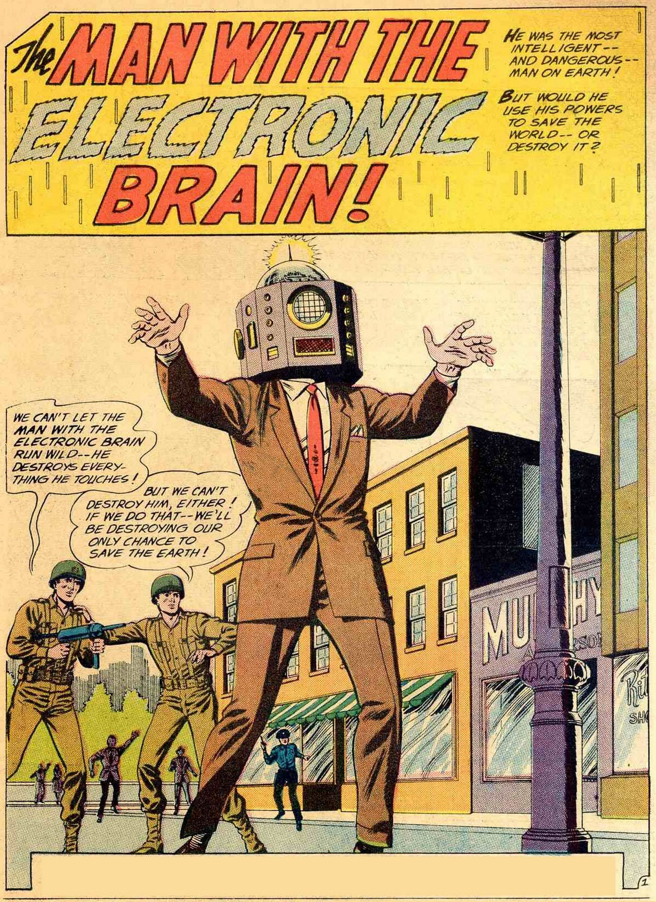

Speaking of the emergence of really smart machines, philosopher Nick Bostrom’s new book, Superintelligence, has just been published in the UK (with the U.S. edition available later this year). Here’s a piece from Clive Cookson’s Financial Times review:

“Since the 1950s proponents of artificial intelligence have maintained that machines thinking like people lie just a couple of decades in the future. In Superintelligence – a thought-provoking look at the past, present and above all the future of AI – Nick Bostrom, founding director of Oxford’s university’s Future of Humanity Institute, starts off by mocking the futurists.

‘We are still far from real AI despite last month’s widely publicised ‘Turing test’ stunt, in which a computer mimicked a 13-year-old boy with some success in a brief text conversation. About half the world’s AI specialists expect human-level machine intelligence to be achieved by 2040, according to recent surveys, and 90 per cent say it will arrive by 2075. Bostrom takes a cautious view of the timing but believes that, once made, human-level AI is likely to lead to a far higher level of ‘superintelligence’ faster than most experts expect – and that its impact is likely either to be very good or very bad for humanity.

The book enters more original territory when discussing the emergence of superintelligence. The sci-fi scenario of intelligent machines taking over the world could become a reality very soon after their powers surpass the human brain, Bostrom argues. Machines could improve their own capabilities far faster than human computer scientists.

‘Machines have a number of fundamental advantages, which will give them overwhelming superiority,’ he writes. ‘Biological humans, even if enhanced, will be outclassed.’ He outlines various ways for AI to escape the physical bonds of the hardware in which it developed. For example, it might use its hacking superpower to take control of robotic manipulators and automated labs; or deploy its powers of social manipulation to persuade human collaborators to work for it. There might be a covert preparation stage in which microscopic entities capable of replicating themselves by nanotechnology or biotechnology are deployed worldwide at an extremely low concentration. Then at a pre-set time nanofactories producing nerve gas or target-seeking mosquito-like robots might spring forth (though, as Bostrom notes, superintelligence could probably devise a more effective takeover plan than him).

What would the world be like after the takeover? It would contain far more intricate and intelligent structures than anything we can imagine today – but would lack any type of being that is conscious or whose welfare has moral significance. ‘A society of economic miracles and technological awesomeness, with nobody there to benefit,’ as Bostrom puts it. ‘A Disneyland without children.'”

Tags: Clive Cookson, Nick Bostrom

Kurt Vonnegut pointed out that some of us get wicker furniture and some get bubonic plague. It seems counterintuitive, but perhaps the kindest thing we can do to help the plagued is to buy more twiggy chairs.

The idea that the best citizen is a good consumer isn’t a new one, though it’s always been complicated because of feelings of personal guilt and concerns about ecology. In his Aeon essay, “The Good Consumer,” Florian Schui, argues against the self-reproach, and while he acknowledges the environmental costs of free-market capitalism, he seems less worried about it than most. The opening:

“Westerners are constantly worrying about consuming too much and living too well. This is not a new concern. For at least the past 2,000 years we have worried about having to pay a price for prosperity. What is perhaps more surprising is that we continue to worry. During the first millennia of human existence, increases in consumption were extremely slow, but over the past 200 years or so industrialisation led to an unprecedented increase in prosperity in the West. This was topped off by a super-increase in the 1950s and ’60s. And yet, we have still not had our comeuppance. Instead, for most Westerners, the principal outcomes have been longer and more comfortable lives.

That said, the benefits of increasing prosperity are distributed highly unequally, making growing inequality perhaps the most pressing economic and social problem of our era. Consumption is one of the areas where inequality is felt most strongly, not so much due to excessive consumption at the top, interestingly enough, but because of increasing deprivation at the bottom. If we want to correct this imbalance, through redistribution, we need to recognise that this will inevitably result in a further substantial increase in overall consumption. That might be no bad thing, providing policymakers make the effort to understand the long tradition of criticising consumption that is almost as old as Western civilisation.”

Tags: Florian Schui

The German soccer team, triumphant at the just-completed World Cup, is called, with a mixture of awe and envy, “The Machine,” which suggests that the squad is somehow circumventing the natural order of things. Of course, that’s not the case. The real machines, however, are now competing at the latest RoboCup, AI’s version of the football competition, and the question is when will machines be able to kick us from soccer dominance the way Deep Blue did Kasparov in chess. Seems an absurd notion, for now. From a new Economist article:

“In the early years of RoboCup, there were huge differences in quality between the teams. No longer. The best of the little league routinely finish their ten-minute-long games with the low scores characteristic of well-matched human teams. Indeed, Dr [Manuela] Veloso’s squad came in second last year, after a penalty shoot-out following a 2-2 game.

Nor need only the players be robots. In a step that many of FIFA’s critics may admire, Dr Veloso and her team are developing automated referees. That will not stop some teams from exploiting decidedly human traits, such as fouling by forcefully bumping into another robot. But it may result in more effective enforcement of things like the maximum kick-speed rule.

What fascinates Dr Veloso most about RoboCup is the execution, during the game, of moves that had not been deliberately inserted into the algorithms controlling the robots. She is ebullient about an unexpected three-way pass and chip, worthy of a minor Messi and his Argentine teammates. Such unanticipated plays are examples of emergent behaviour, a hallmark of artificial intelligence at its highest level, and something she reckons RoboCup teams in all leagues will produce a lot more of with each passing year.

So is 2050 an unrealistic deadline for robots to beat the best humans at football? Half a century is roughly the time that separates ENIAC, America’s first electronic computer, from Deep Blue, the IBM machine that beat chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1997. Judged in that light, RoboCup’s goal does not seem absurd. Indeed, the question may be whether, come 2050, there are still any human football players around who have not been prosthetically enhanced in some way, making them cyborgs. RoboCup v RoboCop, anyone?”

Tags: Manuela Veloso

From the June 9, 1911 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“Gentry, W. Va.–Marion Adkins saw John Willis walking last night with Miss Louisa Berry, whom he was soon to marry, and thinking Miss Berry was his wife, whom he suspected of meeting another man, Adkins shot and instantly killed Willis, the shot almost tearing the victim’s head from his body. Miss Berry is in serious condition from the shock.”

I don’t think a questionable Turing Test means we should be granting robots marriage licenses or social security cards, but there are ethical and legal questions to be addressed as society becomes increasingly automated and performance-enhancement on a grand scale becomes widespread. From Mark Goldfeder’s CNN piece “The Age of Robots Is Here“:

“Robotic legal personhood in the near future makes sense. Artificial intelligence is already part of our daily lives. Bots are selling stuff on eBay and Amazon, and semiautonomous agents are determining our eligibility for Medicare. Predator drones require less and less supervision, and robotic workers in factories have become more commonplace. Google is testing self-driving cars, and General Motors has announced that it expects semiautonomous vehicles to be on the road by 2020.

When the robot messes up, as it inevitably will, who exactly is to blame? The programmer who sold the machine? The site owner who had nothing to do with the mechanical failure? The second party, who assumed the risk of dealing with the robot? What happens when a robotic car slams into another vehicle, or even just runs a red light?

Liability is why some robots should be granted legal personhood. As a legal person, the robot could carry insurance purchased by its employer. As an autonomous actor, it could indemnify others from paying for its mistakes, giving the system a sense of fairness and ensuring commerce could proceed unchecked by the twin fears of financial ruin and of not being able to collect. We as a society have given robots power, and with that power should come the responsibility of personhood.

From the practical legal perspective, robots could and should be people.“

Tags: Mark Goldfeder

I think we’re pretty much done for without superintelligence, though it could also do us in. It’s just a gamble we’ll have to take. From Anders Sandberg’s Guardian article about doomsday scenarios, “The Five Biggest Threats to Human Existence“:

Intelligence is very powerful. A tiny increment in problem-solving ability and group coordination is why we left the other apes in the dust. Now their continued existence depends on human decisions, not what they do. Being smart is a real advantage for people and organisations, so there is much effort in figuring out ways of improving our individual and collective intelligence: from cognition-enhancing drugs to artificial-intelligence software.

The problem is that intelligent entities are good at achieving their goals, but if the goals are badly set they can use their power to cleverly achieve disastrous ends. There is no reason to think that intelligence itself will make something behave nice and morally. In fact, it is possible to prove that certain types of superintelligent systems would not obey moral rules even if they were true.

Even more worrying is that in trying to explain things to an artificial intelligence we run into profound practical and philosophical problems. Human values are diffuse, complex things that we are not good at expressing, and even if we could do that we might not understand all the implications of what we wish for.

Software-based intelligence may very quickly go from below human to frighteningly powerful. The reason is that it may scale in different ways from biological intelligence: it can run faster on faster computers, parts can be distributed on more computers, different versions tested and updated on the fly, new algorithms incorporated that give a jump in performance.

It has been proposed that an “intelligence explosion” is possible when software becomes good enough at making better software. Should such a jump occur there would be a large difference in potential power between the smart system (or the people telling it what to do) and the rest of the world. This has clear potential for disaster if the goals are badly set.•

Tags: Anders Sandberg

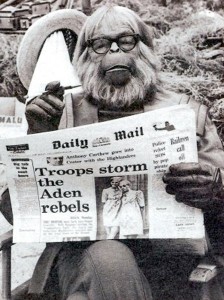

Pierre Boulle wasn’t exactly embarrassed, just perplexed, by the success of The Planet of the Apes, his 1963 French novel which became an unlikely American film franchise in a time before franchises were really a thing. It seemed to him an odd, little fantasy that shouldn’t have approached the popularity of something like the Oscar-winning The Bridge Over the River Kwai, yet it did. A good deal of the big-screen appeal was the remarkable make-up work of John Chambers, who made monkeys out of men (and women), and Boulle was aware of this contribution, but he still couldn’t account for the reception. Here’s a (rough) translation into English of an interview Boulle did about Apes, though I’m not sure of the source:

Question:

What inspired you to write Planet of the Apes?

Pierre Boulle:

I do not really remember. I think it was during a visit to the zoo, watching the gorillas. I was impressed by their almost human expressions. This led me to imagine what would a man/monkey relationship. Some believe that I had King Kong in mind when I wrote my book, but this is totally false. Frankly, I have never considered it one of my best novels, but more like a fun fantasy. I’m not very happy with the final result: I think I could have done better with parts of the book.

Question:

Do you think the film is faithful to the book?

Pierre Boulle:

You should never ask that of an author whose novel has been made into a film. There have been a lot of changes, and some very disconcerting. My planet had three suns for example. The first part of the film is excellent, and the monkeys’ makeup is particularly successful. I do not like the end with the Statue of Liberty. I prefer mine where finally we were not on Earth but of course on another planet. But critics loved it, so maybe I’m a bad judge. I knew from the outset that the producer Arthur P. Jacobs wanted this. He had it in mind from the first day and told me about it. I replied ‘Why not try it?’ Critics have approved, but I’m a little more rational writer and I prefer everything to be explained from A to Z. I am also completely unable to work in a group, which seems a necessity in the production of a film. When I write, I am alone. I give the book to my editor, and do not want to change anything, to the last comma.

Question:

But you have started working on the sequel to Planet of the Apes?

Pierre Boulle:

True. After the success of the first film, Arthur asked me to write more for him. It was called Planet of Women. They initially agreed, but then there were so many changes. I read the script of the Secret of the Planet of the Apes, and it interested me because it had nothing to do with my work. It was completely different. This does not bother me because the film did not ultimately matter to me. I rarely see movies. It is also strange that what I write inspires such visual and adaptable on-screen elements.

What would you attribute the success of the Planet of the Apes?

Pierre Boulle:

Honestly, I have no idea.•

Tags: Arthur P. Jacobs, Pierre Boulle

I don’t think there’s been an American stand-up comic over the last five years who’s worked at close to the same level as Maria Bamford, CK and Oswalt and Burr included, so I was happy to see her the subject of an insightful profile by Sara Corbett in the New York Times Magazine. Stand-up mostly attracts people who have some significant degree of instability, but does the very act of writing and telling jokes exacerbate those issues? It certainly doesn’t seem to be a palliative, not the talk therapy you might expect, the repetition perhaps more deeply ingraining the problems than releasing them. From the Times piece:

“Bamford has a song that she sometimes performs onstage called ‘My Anxiety Song.’ It has no melody. Instead, it sounds more like an incantation, a desperate verbal hum. ‘If I keep the ice-cube trays filled,’ she chants, ‘no one will diiiiieeee.’ She continues, in a monotone, ‘As long as I clench my fists at odd intervals, then the darkness within me won’t force me to do anything inappropriate or sexual’ — here, she drops her voice a couple of notes — ‘at dinner partieeeees. . . . ‘

This, she is saying, is the agony of O.C.D., the skewed sense of cause and effect that first began to plague her when she was about 10. According to the National Institutes of Health, about 2.2 million adult Americans contend with some form of obsessive-compulsive disorder. It’s not uncommon for the symptoms to appear during childhood. Bamford is patient when explaining the particulars, aware that when she jokes about having wanted to chop up her family into bits or imagining what it would be like to lick a urinal, it can make her sound weird and also scary. But she makes a distinction: It’s the thoughts that are weird and scary, not the person. And while most of us are prone to having fleeting notions that would qualify as inappropriate, in the mind of someone with O.C.D., they are more likely to lodge themselves and repeat. The thoughts don’t tend to inspire action, only fear. It’s like having a homegrown terrorist in the brain.”

Tags: Maria Bamford, Sara Corbett

Naked Guitar Lessons via Webcam – $50

I am a guitar teacher who happens to be a little bit of a nudist (male). I am now accepting students via webcam across the country. The is no sexual intended or implied, it is just my lifestyle. I feel more comfortable in the nude and will make it easier for me to help you master the guitar.

I can teach all levels from beginner to advanced and am flexible on times.

Imagine the ease of learning to master the ax without having to go anywhere!

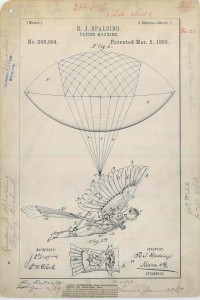

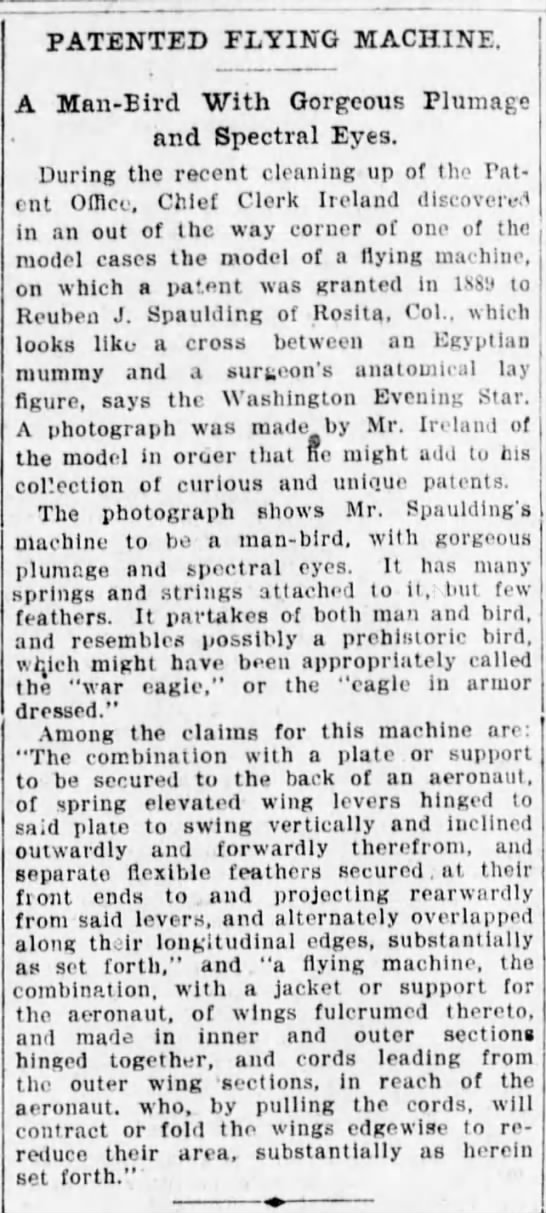

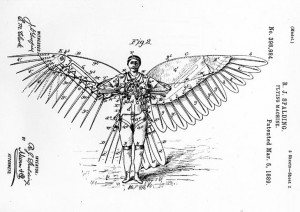

Reuben Jasper Spalding’s flying machine never actually flew, but neither did Leonardo da Vinci’s. The Colorado-based inventor devised a breathtaking design for a manned-flight contraption in 1889 (patent here), and even if there wasn’t much chance the sun would get the opportunity to melt its wings, it was still an impressive apparatus. From an article about a rediscovered model of the contrivance, in the October 12, 1903 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Tags: Chief Ireland, R.J. Spalding, Reuben Jasper Spalding, Reuben Jasper Spaulding

Eventually you’ll have the implant, promised Larry Page several years ago, explaining that Google would someday literally be in your head, but isn’t it there already? Don’t we already see things radically differently, our brains having been tapped from the outside? Hasn’t that already made things better and also worse?

From Robert Pogue Harrison’s New York Review of Books anti-disruption screed,”The Children of Silicon Valley,” which I don’t agree with in the macro, though I acknowledge it makes some salient points:

“Our silicon age, which sees no glory in maintenance, but only in transformation and disruption, makes it extremely difficult for us to imagine how, in past eras, those who would change the world were viewed with suspicion and dread. If you loved the world; if you considered it your mortal home; if you were aware of how much effort and foresight it had cost your forebears to secure its foundations, build its institutions, and shape its culture; if you saw the world as the place of your secular afterlife, then you had good reasons to impute sinister tendencies to those who would tamper with its configuration or render it alien to you. Referring to all that happened during the ‘dark times’ of the first half of the twentieth century, ‘with its political catastrophes, its moral disasters, and its astonishing development of the arts and sciences,’ Hannah Arendt summarized the human cost of endless disruption:

The world becomes inhuman, inhospitable to human needs—which are the needs of mortals—when it is violently wrenched into a movement in which there is no longer any sort of permanence.

The twenty-first century has only aggravated the political, moral, social, and environmental concussions of the twentieth. There would be reason to applaud the would-be world-changers and start-up companies of Silicon Valley if they made it their business to resist or reverse this process of planetary upheaval, the way environmentalists seek to do with the wounds we have afflicted on nature. Sadly they have no such militancy in their souls, nor much thoughtfulness. With a few exceptions, our new tech armies rarely take the time to think through what they are doing. Or if they do, they tend to think in ways that only add to the turmoil and agitation.

Silicon Valley, and everything it stands for metonymically in our culture, has indeed affected billions of people around the planet. The innovations have come fast and furious, turning the past four decades into a series of ‘before and after’ divides: before and after personal computers, before and after Google, before and after Facebook, iPhones, Twitter, and so forth. In the silicon age, ‘changing the world’ means at bottom finding new and more ingenious ways to turn my computer or smart phone into my primary—and eventually my only—access to ‘reality.’

In truth Silicon Valley does not change the world as much as it changes my way of being in it, or better, of not being in it.”

Tags: Robert Pogue Harrison

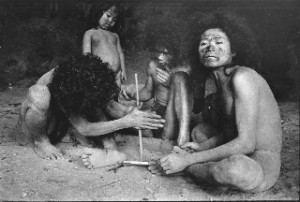

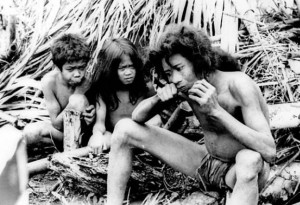

Hoaxes that work do so because they play upon a deep-seated fear or satisfy a psychological want–a need, even. That’s why we’re able to suspend disbelief about something that seems ridiculous in retrospect. When I published the post about a passage from Daniel Lieberman’s recent book, The Story of the Human Body, it reminded me that he (briefly) touches on the story of the Tasaday people, a “stone-age” tribe discovered in 1971 in Philippine caves, which was untouched by wars hot and cold, threats of nuclear disaster, and trends in which clans–families–were unable to stay together. It was a sensation that National Geographic granted a cover and a 32-page story, and, of course, it was a hoax. But it had a good, long run, with Charles Lindbergh himself spending some of his final moments of life writing the foreword for a popular book about this make-believe people. The opening of a 1986 New York Times article by Seth Mydans, written when the work finally began to stop working:

“MANILA, May 12— After more than a decade, scientists and reporters have returned to visit a remote Stone Age tribe called the Tasaday, and found that its earlier contacts with the outside world have set it on what appears to be an irreversible road to change.

The new visits have also reopened a debate on the authenticity of the Tasaday, who have now been found to possess bits of clothing, knives, bows and arrows, a mirror and domesticated dogs.

In interviews, two anthropologists who recently revisited the tribe said these new possessions, which had aroused the scepticism of Swiss and German reporters who saw them recently, were an expectable product of the tribe’s first contacts with outsiders in the early 1970’s.

Discovered in 1971

The scientists said they now feared that, if new protective measures were not taken, an influx of researchers, journalists and tourists would destroy their fragile way of life, already imperiled by the approach of loggers, slash-and-burn farmers and the armed insurgencies that share the forests of the southern Philippine island of Mindanao.

The Tasaday, a group of fewer than 30 people, were discovered in 1971 and drew international attention as a cave-using tribe of hunter-gatherers who dressed in orchid leaves and bark, knew no enemies and had no words for war, for ocean or for other peoples.

When two groups of journalists trekked into the jungle recently, they found the tribe members wearing bits and pieces of clothing and displaying other signs of outside influence, and the visitors raised cries of ‘hoax’ and ‘fairy tale.’

The two anthropologists who visited soon afterward, however, in the company of John Nance, author of a book on the tribe, and a television crew, said the changes were not surprising, and indeed enhanced the scientific interest of the group.

‘Textbook Case of Change’

‘We’re seeing a textbook case of social change, compressed in time,’ said one of the anthropologists, Jesus Peralta, who is curator of anthropology for the National Museum of the Philippines.

The other anthropologist who visited, Carlos Fernandez, said, ‘Before we first met them, they were purely forest gatherers.’

‘Then they learned to use a blade, to set traps and now they are learning to hunt,’ he went on. ‘Before long they will try their hand at planting.

‘This is one of the most exciting subjects for an anthropological investigator.’

Mr. Nance, the author of The Gentle Tasaday, who traveled last month to Mindanao with the two anthropologists, said the Tasaday’s preference for T-shirts and other articles of clothing was only natural. ‘If leaves were better, we’d all be wearing leaves,’ he said. Brides From Another Tribe

The scientists said the question of a hoax had always been present and remained a possibility. But they said such details as the stone tools and the language used by the Tasaday would be extremely difficult to fabricate.

‘Unless another anthropologist produces conflicting data, then the literature stands,’ said Mr. Peralta.

Many of the changes were thought to be the result of two outside influences: a tribal hunter named Dafal, and the marrying of women from a nearby tribe called the Blit.

A small group of primarily male cousins, the Tasaday’s main request of the scientists who discovered them was for brides. Mr. Peralta said that, in the years since then, 15 Blit women and two men had married into the tribe.

Trapping and Weapons

Dafal and the Blit spouses brought with them clothing, beads, knives, rice and cigars, the scientists said.

They also said they taught them to trap and use bows and arrows to supplement their traditional diet of yams, the hearts of palms and rattan, and fish, frogs and tadpoles.

‘They were already in transition when we first met them,’ Mr. Nance said, referring to their earlier contacts with Dafal. ‘Scientists worked to reconstruct what their life had been like before that, and people took the reconstruction as the current reality.’

He said this had led to misconceptions and to the recent accusations of a hoax.”

Tags: Charles Lindbergh, Daniel Lieberman, Jesus Peralta, John Nance, Manuel Elizalde, Seth Mydans

At this point, the question may not be whether cars are going to transition, at last, to electric, but whether solar farms will be able to provide enough relatively clean electricity to meet the demand. China is certainly on board with EV, having received an unlikely nudge from SARS. From Dennis Taylor at the Monterey County Herald:

“What was lost on that audience, he said, is the fact that China now has more than 200 million electric-vehicle drivers — a statistic that by next year is expected to eclipse the total number of drivers in the United States.

A big part of the electric-vehicle surge in China can be traced to the 2002 epidemic of the SARS virus, during which many mass-transit users became afraid to board a bus and discovered that for $200 to $450 they could instead purchase a 1-horsepower electric motorcycle.

The alternative caught on: In 2013, the Chinese bought 37 million two-wheeled electric vehicles, Jurvetson said.

Electric motorcycles (which look a lot like bullet bikes), electric cars, even electric boats were among the vehicles showcased just outside the Hyatt’s convention center as Jurvetson spoke to a large and enthusiastic crowd at the symposium, drawing parallels between the future of electric cars and commercial space-travel vehicles that are the focus of SpaceX.”

Tags: Dennis Taylor

Manias are nothing new in America, and one that stretched from Huntington Beach to Thailand was that of The Children of God, a cult infamous for Flirty Fishing and Hookers for Jesus, which was rife with child abuse and perhaps worse. The group was the subject of “A Violent Act Jolts the Serenity of the Peace-Preaching Children of God,” a 1975 article by Jerome Doolittle of OUI, a middling vagina periodical. The cult “rebranded” itself a few years after this piece was published. The opening:

Manias are nothing new in America, and one that stretched from Huntington Beach to Thailand was that of The Children of God, a cult infamous for Flirty Fishing and Hookers for Jesus, which was rife with child abuse and perhaps worse. The group was the subject of “A Violent Act Jolts the Serenity of the Peace-Preaching Children of God,” a 1975 article by Jerome Doolittle of OUI, a middling vagina periodical. The cult “rebranded” itself a few years after this piece was published. The opening:

The Victory Monument in Bangkok sits in the middle of a huge traffic circle. All around the circle are bus stops. Vendors sit on the sidewalks in the heat, selling mangoes and durians and mangosteens and little pieces of broiled chicken liver spitted on bamboo slivers. People are everywhere, practically all of them Buddhists. Three are not, though. They are:

- Little John, 20 a Thai student wearing a faded-blue T-shirt decorated with a giant Levi Strauss & Co. emblem

- Gang, a four-year-old Thai boy

- Shema, an 18-year-old American girl who is braless in accordance with the precepts of her religion, which is Christianity as interpreted and amended by David Brandt Berg, 55, aka Moses David.

The three are passing out Thai translations of a brief tract called ‘You Gotta Be a Baby.’ It reads, in part: Dear Lord, please forgive me for being bad and naughty and deserving a good spanking! Thank You so much for sending Jesus, Your son, to take my spanking for me.

They are distributing the tracts on behalf of a sect called the Children of God, and the distribution process is know as litnessing– witnessing by literature. For a time there, the Children of God in Bangkok had to cool it on the litnessing, but now the hullabaloo over the murder has pretty much died down and they are back at it again, as other Children of God are doing in 100 countries all over the earth. Praise God!

In Bangkok the Children of God work out of a former noodle shop in an alley behind a movie theater. The neighborhood is not fashionable and neither is the theater. One day not long ago, to give you an idea, it was playing a winner called The Crazy Boys at the Supermarket.

The steel folding shutters of the noodle shop were almost closed, leaving just enough of a gap for someone to squeeze through. Since the murder, no one at C.O.G. headquarters has been anxious to overexpose himself. Inside were two American males, caught in the tension zone between boyhood and manhood, complexions not quite cleared up yet. Around their necks, they wore chains from which hung small metal yokes, symbols of their servitude to God. On their faces, they wore smiles- the slightly awkward smiles offered by people told to smile for the camera.

OUI magazine? They were sorry, but they hadn’t heard of it. It sounded interesting, though; the human form was beautiful, nothing to be ashamed of. (Or parts of it, at any rate. In the letters of Moses, it is written: “I don’t see anything beautiful about these crotch shots of the women sticking their fannies right under your nose.” And it is further written: “You’d rather see some beautifully draped cloth covering that uncomely part” and making her form even more attractive, than just plain corny-porny, ugly-wugly, nitty-gritty, smarty-smelly, hara-kiri crotches!”)

Perhaps I would like to stop by a little later in the day, when Gibeah would be there. Gibeah speaks for us. What hotel was I in? The Trocadero, hadn’t I said? What room number had I said? I hadn’t said, but it was 421. (Why would they want to know the room number? Did they want to visit me? With what in mind? I was nervous because of the murder.)

When I went back, it turned out that the Children of God were nervous about my motives, too.•

Tags: Jerome Doolittle

Via the excellent Browser, here’s the opening of “Choosing a Driving Plan: 2035, United States,” a post at A History of the Future which examines automobiles in a post-driver, post-ownership landscape:

“The ‘driverless’ car revolutionised every aspect of transportation — particularly the business model. This brochure demonstrates how people struggled to come to grips with the new world:

Life used to be simple. If you wanted to travel, all you had to do was buy a car and put gas in it every so often. Sure, keeping a car was expensive, and it bled value every minute you weren’t using it, and you had to pay for parking and repairs and insurance, and you wasted thousands of hours of your life in the mindless drudgery of driving, but at least you knew you had absolutely no choice in the matter.

Well, it’s 2035 now, and while we’re blessedly free from the monotony and expense of driving, we’re also faced with a bewildering range of options for getting from A to B. The plummeting cost of cars (we can surely drop the term ‘driverless’ by now), along with their tight network integration, has seen a thousand flowers bloom in the burgeoning ‘cars as a service’ sector.

With so many choices available it’s easy to get confused, but don’t worry: we’re here to help you find your perfect car plan!

(Before we begin, those Pay As You Go plans that seem so cheap with their free miles and entertainment? Unless you’re a penniless hermit who only makes ten trips a year, or you hate the idea of being able to travel wherever you want, whenever you want, forget it.)

Now we’ve gotten that out of the way, here a few general tips on finding a good plan.

First off, don’t go for flat-rate pricing for ‘car minutes’ or ‘car miles.'”

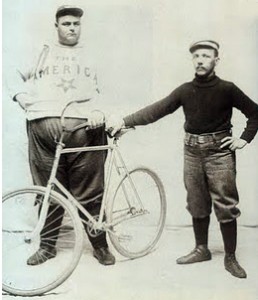

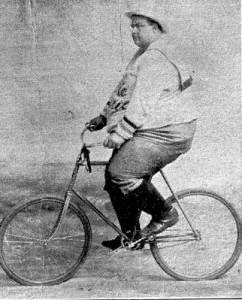

From the January 18, 1910 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“Peoria, Ill.–Leonard Bliss, better known as “Baby” Bliss, at one time supposed to be the largest man in the United States, was brought from his home in Bloomington last night, to the Peoria Hospital at South Bartonville, hopelessly insane. Bliss weighed 525 pounds when placed on the scales at the asylum. During the bicycle craze he rode wheel over the United States and Europe as a demonstrator of the make of machine. He is 37 years of age.”

Tags: Leonard "Baby" Bliss

- Dad Accused Of Hiding 16 Bags Of Heroin Inside Baby’s Diaper

- The Down And Dirty Of Vagina Smuggling

- Casey Kasem’s Body Is Reportedly Missing

- True Confessions of a Smelly Girl

- That Makes Me Want To Vomit In My Mouth

- Man Reveals He’s Turned Off By His Partner’s Aging Body

- Man Stabs Watermelon, Gets Arrested

- Apparently, Eva Mendes Is Pregnant With Ryan Gosling’s Baby, But Hey Girl, Who Knows

- Nestle Apologizes For ‘Penis’ Shape On Candy Bar

- Pat Robertson Blames Witchcraft For Boy’s Stomach Pains

10 search-engine keyphrases bringing traffic to Afflictor this week:

- michel siffre embedded in an iceberg

- new yorker article about philip k dick

- humans racing horses

- louis ck pinocchio joke

- the next war may be fought by airplanes with no men in them at all

- dick cavett’s article on walter winchell

- why is flint america’s most dangerous city?

- was papa doc a witch doctor?

- mail sent by pneumatic tubes in new york city

- coffee served by pneumatic tubes