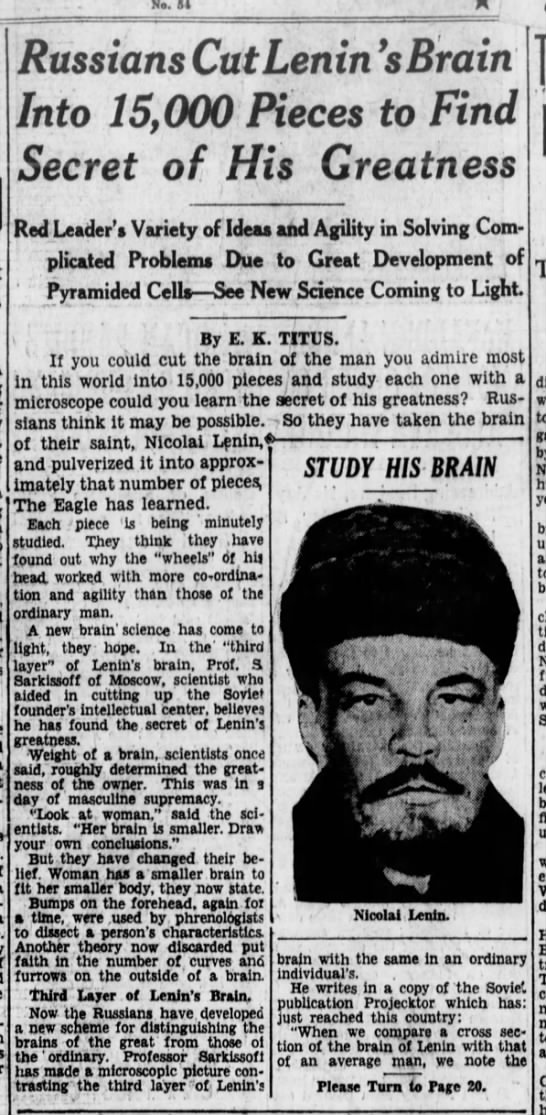

What would a person with a 1,000 IQ be capable of? How can our relatively puny intelligences even fathom such a thing?

In Stephen Hsu’s Nautilus article “Super-Intelligent Humans Are Coming,” he walks through the process of genetic modification which would lead to heretofore unknown brain power, with the average IQ being ten times what it currently is, which may not be in the immediate offing but aspects of which are closer than might be imagined. An excerpt:

Super-intelligence may be a distant prospect, but smaller, still-profound developments are likely in the immediate future. Large data sets of human genomes and their corresponding phenotypes (which are the physical and mental characteristics of the individual) will lead to significant progress in our ability to understand the genetic code—in particular, to predict cognitive ability. Detailed calculations suggest that millions of phenotype-genotype pairs will be required to tease out the genetic architecture, using advanced statistical algorithms. However, given the rapidly falling cost of genotyping, this is likely to happen in the next 10 years or so. If existing heritability estimates are any guide, the accuracy of genomic-based prediction of intelligence could be better than about half a population standard deviation (meaning better than plus or minus 10 IQ points).

Once predictive models are available, they can be used in reproductive applications, ranging from embryo selection (choosing which IVF zygote to implant) to active genetic editing (for example, using CRISPR techniques). In the former case, parents choosing between 10 or so zygotes could improve the IQ of their child by 15 or more IQ points. This might mean the difference between a child who struggles in school, and one who is able to complete a good college degree. Zygote genotyping from single cell extraction is already technically well developed, so the last remaining capability required for embryo selection is complex phenotype prediction. The cost of these procedures would be less than tuition at many private kindergartens, and of course the consequences will extend over a lifetime and beyond.

The corresponding ethical issues are complex and deserve serious attention in what may be a relatively short interval before these capabilities become a reality. Each society will decide for itself where to draw the line on human genetic engineering, but we can expect a diversity of perspectives. Almost certainly, some countries will allow genetic engineering, thereby opening the door for global elites who can afford to travel for access to reproductive technology. As with most technologies, the rich and powerful will be the first beneficiaries. Eventually, though, I believe many countries will not only legalize human genetic engineering, but even make it a (voluntary) part of their national healthcare systems.

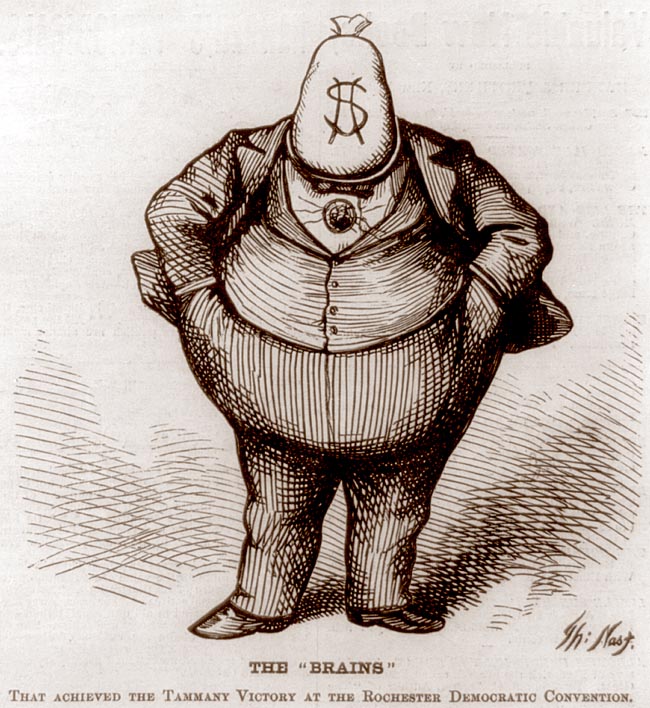

The alternative would be inequality of a kind never before experienced in human history.•