No one is more moral for eating pigs and cows rather than dogs and cats, just more acceptable.

Dining on horses, meanwhile, has traditionally fallen into a gray area in the U.S. Americans have historically had a complicated relationship with equine flesh, often publicly saying nay to munching on the mammal, though the meat has had its moments–lots of them, actually. From a Priceonomics post by Zachary Crockett, a passage about the reasons the animal became a menu staple in the fin de siècle U.S.:

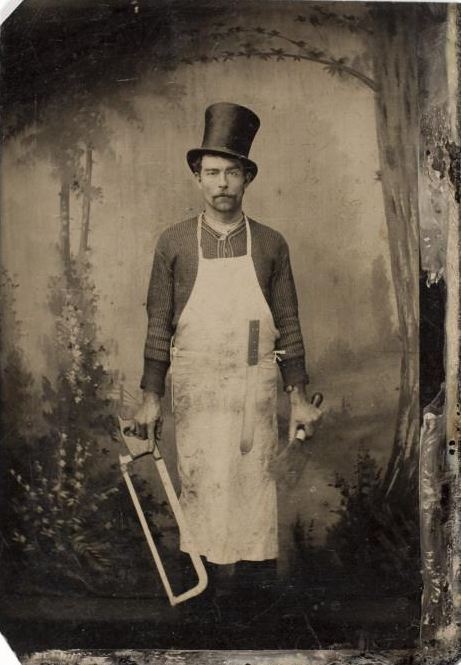

Suddenly, at the turn of the century, horse meat gained an underground cult following in the United States. Once only eaten in times of economic struggle, its taboo nature now gave it an aura of mystery; wealthy, educated “sirs” indulged in it with reckless abandon.

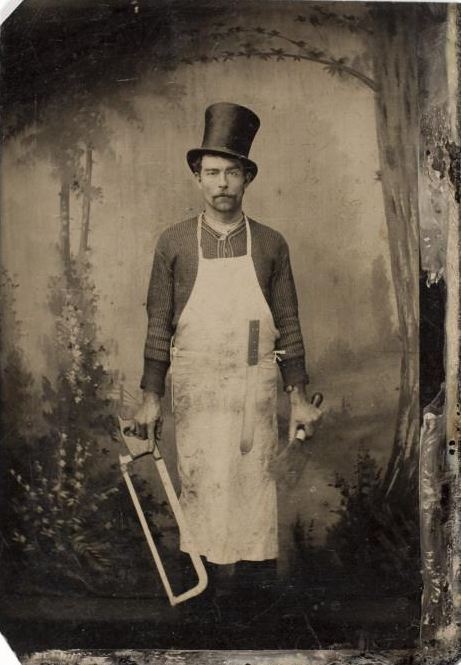

At Kansas City’s Veterinary College’s swanky graduation ceremony in 1898, “not a morsel of meat other than the flesh of horse” was served. “From soup to roast, it was all horse,” reported the Times. “The students and faculty of the college…made merry, and insisted that the repast was appetizing.”

Not to be left out, Chicagoans began to indulge in horse meat to the tune of 200,000 pounds per month — or about 500 horses. “A great many shops in the city are selling large quantities of horse meat every week,” then-Food Commissioner R.W. Patterson noted, “and the people who are buying it keep coming back for more, showing that they like it.”

In 1905, Harvard University’s Faculty Club integrated “horse steaks” into their menu. “Its very oddity — even repulsiveness to the outside world — reinforced their sense of being members of a unique and special tribe,” wrote the Times. (Indeed, the dish was so revered by the staff, that it continued to be served well into the 1970s, despite social stigmas.)

The mindset toward horse consumption began to shift — partly in thanks to a changing culinary landscape. Between 1900 and 1910, the number of food and dairy cattle in the US decreased by nearly 10%; in the same time period, the US population increased by 27%, creating a shortage of meat. Whereas animal rights groups once opposed horse slaughter, they now began to endorse it as more humane than forcing aging, crippled animals to work.

With the introduction of the 1908 Model-T and the widespread use of the automobile, horses also began to lose their luster a bit as man’s faithful companions; this eased apprehension about putting them on the table with a side of potatoes (“It is becoming much too expensive a luxury to feed a horse,”argued one critic).

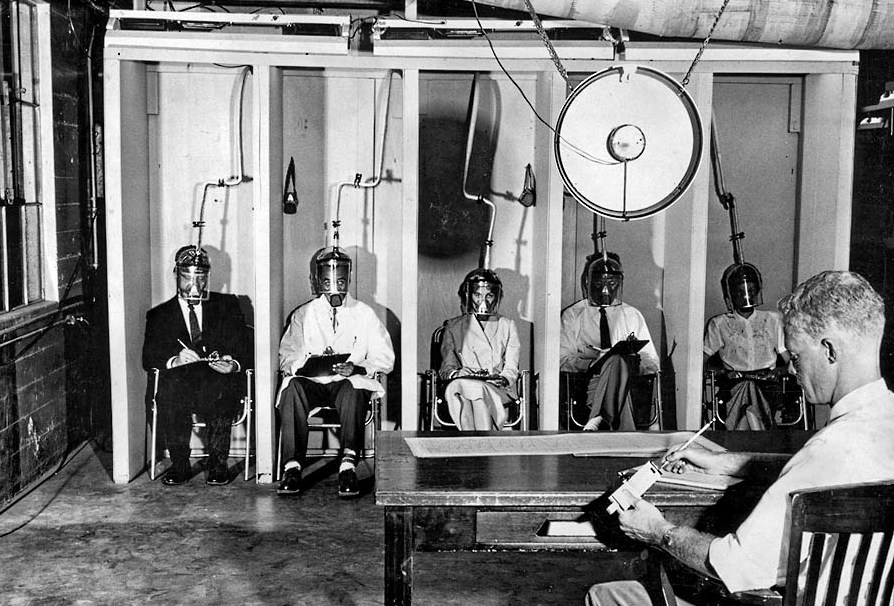

At the same time, the war in Europe was draining the U.S. of food supplies at an alarming rate. By 1915, New York City’s Board of Health, which had once rejected horse meat as “unsanitary,” now touted it is a sustainable wartime alternative for meatless U.S. citizens. “No longer will the worn out horse find his way to the bone-yard,” proclaimed the board’s Commissioner. “Instead, he will be fattened up in order to give the thrifty another source of food supply.”

Prominent voices began to sprout up championing the merits of the meat.•