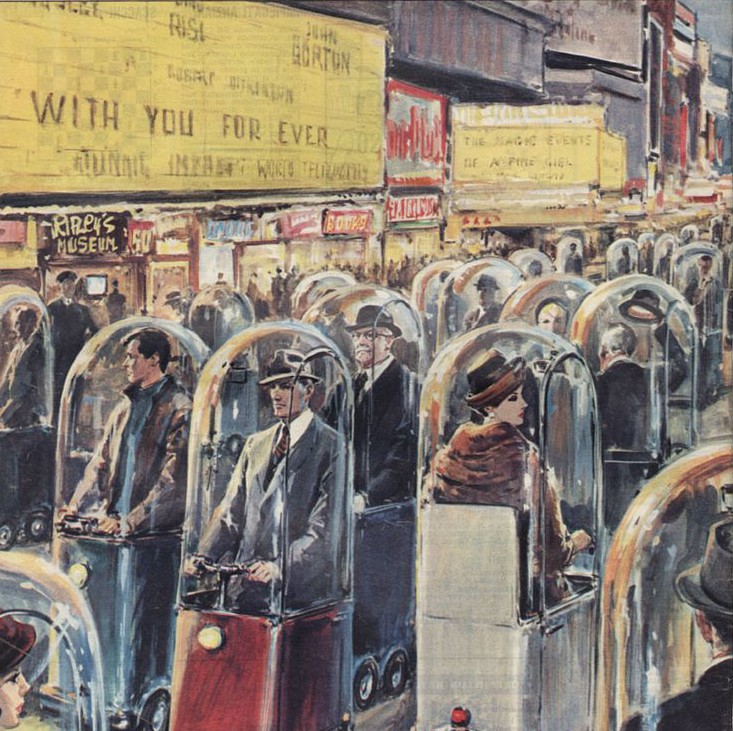

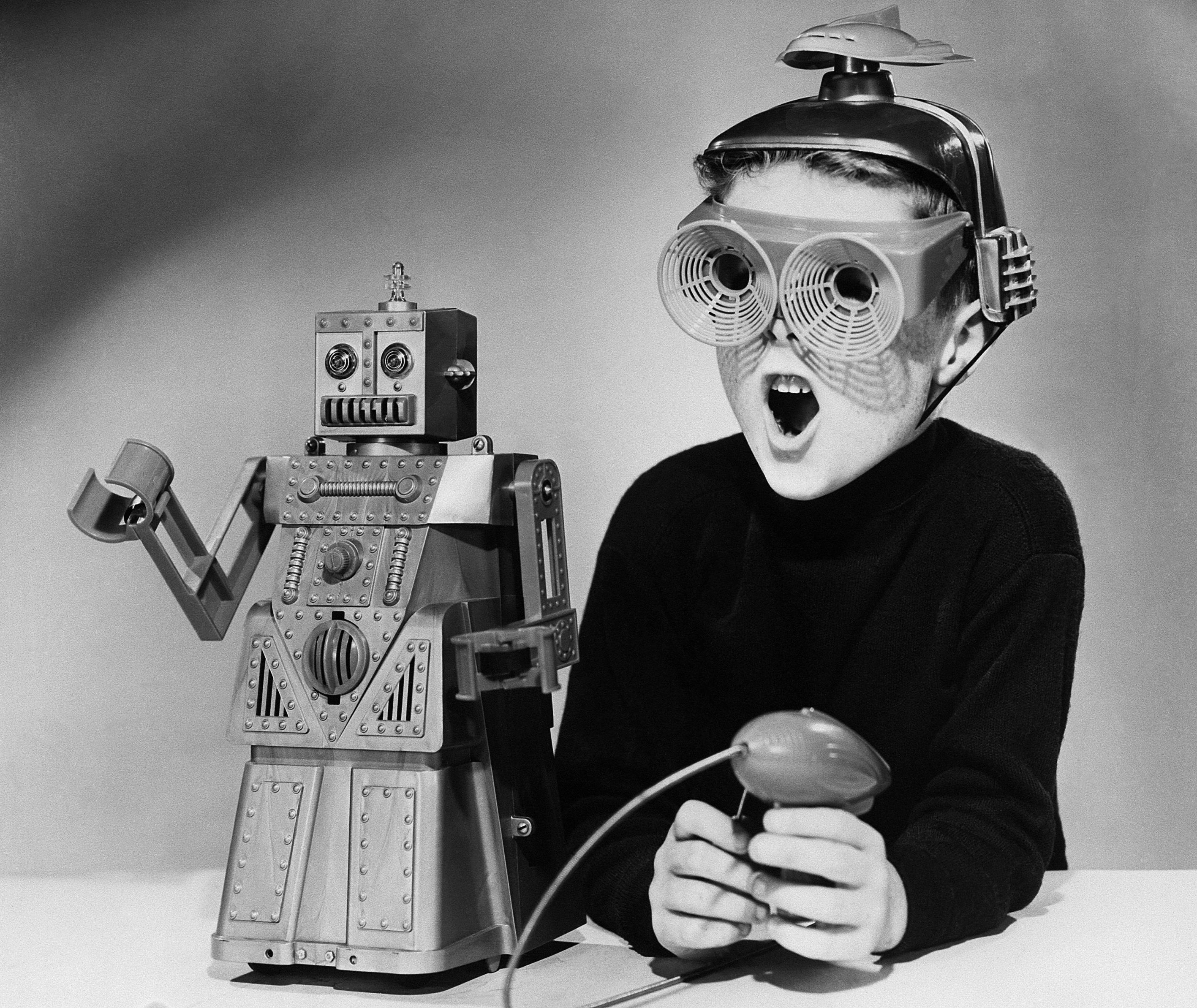

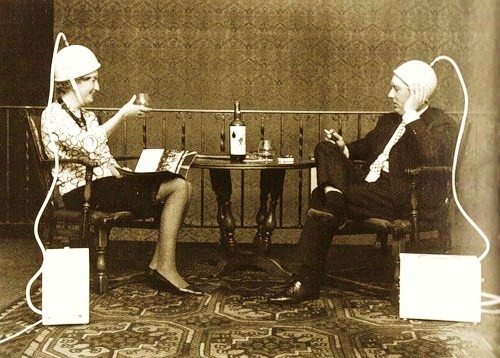

Feedback loops between humans and machines, a new type of conversation and one that will ultimately be conducted in hushed tones, is one of the goals of the Internet of Things. Measuring our minutiae will lead to a smarter society, but there’ll really be no way to opt out. The opening of Quentin Hardy’s New York Times Q&A with IoT enthusiast Tim O’Reilly:

Question:

The way most companies sell it, the Internet of Things is about gaining efficiency from putting all kinds of devices online. What is wrong with that definition?

Tim O’Reilly:

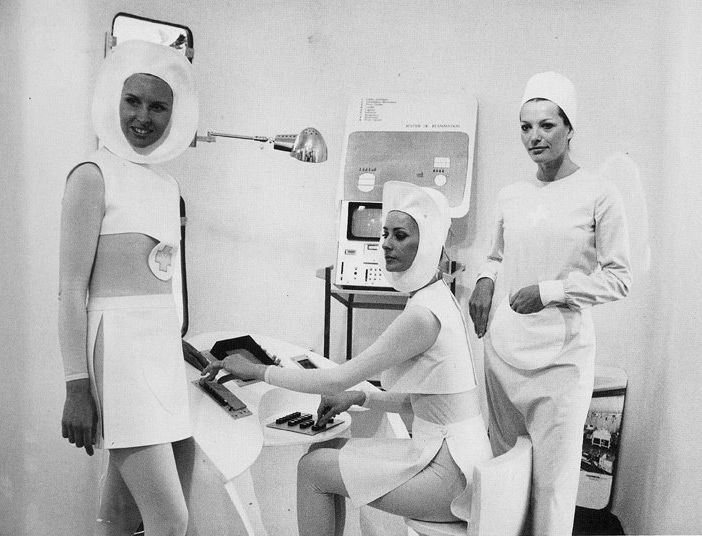

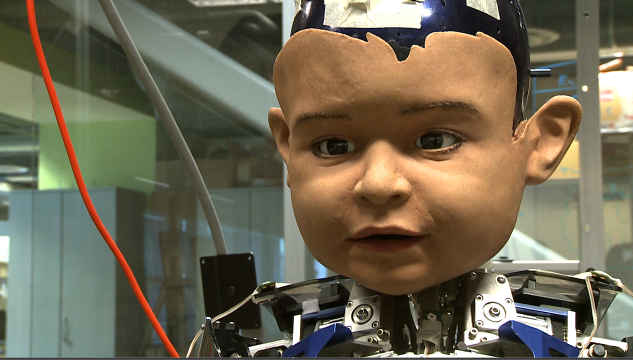

The IoT is really about human augmentation. The applications are profoundly different when you have sensors and data driving the decision-making.

Question:

Can you give me an example?

Tim O’Reilly:

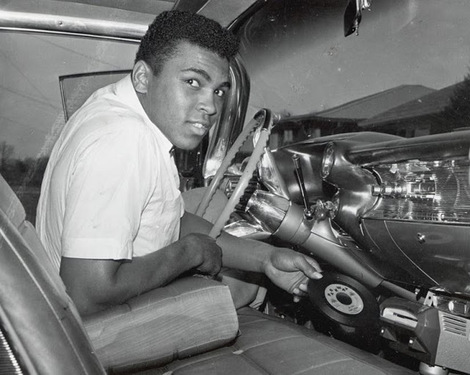

Uber is a company built around location awareness. An Uber driver is an augmented taxi driver, with real-time location awareness. An Uber passenger is an augmented passenger, who knows when the cab will show up. Uber is about eliminating slack time and worry.

People would call it “IoT” if there was a driverless car, but it already is part of the IoT. You can measure, test and change things dynamically. The IoT is about the interpolation of computer hardware and software into all sorts of things.

Question:

But the IoT isn’t just about one sensor in two-way contact with a remote cloud computing battery of servers, or a driver and a rider with a smartphone. There are going to be lots of different data sets, and lots of different feedback loops.

Tim O’Reilly:

The characteristics are that things are contingent, in relationship with other data. They are on demand. They are load-balanced, and aware of other parts of the system. That is why you get things like congestion pricing. It’s a more context-oriented world, because there is better data.

Question:

Why do you think this isn’t better understood?

Tim O’Reilly:

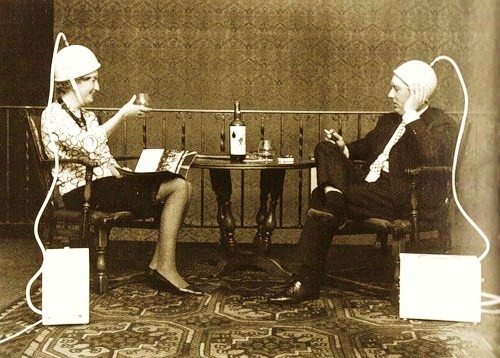

We’re not letting the IoT teach us enough about what is possible once you add sensors. There is a complex interplay of humans, interfaces and machines. A big question is, How do we create feedback loops from devices to humans?•