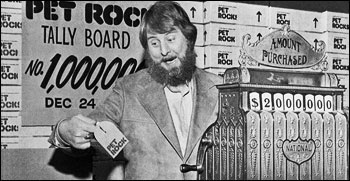

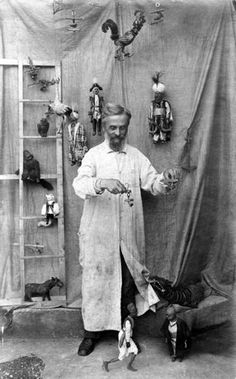

Most of us do not get what we deserve in life, and struggling adman Gary Dahl did not merit wealth because he boozily dreamed up a novelty that ever so briefly became a national sensation. His Pet Rock was a gag that went large for a few months in the mid-’70s and minted him a millionaire. You could have thought of the Pet Rock, but you didn’t. Dahl did. Read what you will about Me Decade zeitgeist into the popularity of the packaged “domesticated” Mexican beach stones, but the joke about “pets” that need no affection nor could offer any was funny. Well, for about five minutes. And that was long enough for Dahl to cash in.

The huckster-ish marketer recently passed away. The New York Times obituary desk writer Margalit Fox, who has been for years–along with the dearly departed David Carr–my favorite stylist at the publication, penned Dahl’s post-mortem. An excerpt from Fox follows another from a 1975 People magazine piece which bemoaned the rocky story.

________________________________

From People:

It is, apparently, an idea whose moment is regrettably here. Like the Hula Hoops, mink-lined shoehorns and giant paper clips of yore, Pet Rocks are the new national mania, selling like crazy in stores ranging from I. Magnin in San Francisco to Neiman-Marcus in Dallas. Says Dennis Hamel, gift buyer at New York’s Bloomingdale’s: “It’s unbelievable. We’re selling 400 a day.”

They are not, of course, prosaic pebbles, but egg-shaped Mexican beach stones, nestled on a bed of excelsior and packaged in a little doggy carrying case, equipped with breathing holes. The kit, selling for $4, is the concoction of Gary Dahl, a 38-year-old advertising copywriter from Los Gatos, Calif., who claims he hit on the idea while boozing with pals. He attributes its success to the fact that “people are so damn bored, tired of all their problems. This takes them on a fantasy trip—you might say we’ve packaged a sense of humor.”•

________________________________

From Fox:

Gary Dahl, the man behind that scheme — described variously as a marketing genius and a genial mountebank — died on March 23 at 78. A down-at-the-heels advertising copywriter when he hit on the idea, he originally meant it as a joke. But the concept of a “pet” that required no actual work and no real commitment resonated with the self-indulgent ’70s, and before long a cultural phenomenon was born.

A modern incarnation of “Stone Soup” as stirred by P. T. Barnum, Pet Rocks made Mr. Dahl a millionaire practically overnight. Though the fad ran its course long ago, the phrase “pet rock” endures in the American lexicon, denoting (depending on whether it is uttered with contempt or admiration) a useless entity or a meteoric success.

But despite the boon Pet Rocks brought him, Mr. Dahl came to regret the brainstorm that gave rise to them in the first place.

Mr. Dahl’s brainstorm began, as many do, in a bar.

One night in the mid-’70s, he was having a drink in Los Gatos, the Northern California town where he lived for many years. At the time, he was a freelance copywriter (“that’s another word for being broke,” he later said), living in a small cabin as a self-described “quasi dropout.”

The bar talk turned to pets, and to the onus of feeding, walking and cleaning up after them.

His pet, Mr. Dahl announced in a flash of bibulous inspiration, caused him no such trouble. The reason?

“I have a pet rock,” he explained.•